The Project Gutenberg eBook of Watchbird

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Watchbird

Author: Robert Sheckley

Illustrator: Ed Emshwiller

Release date: August 2, 2009 [eBook #29579]

Most recently updated: September 12, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Greg Weeks, Stephen Blundell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WATCHBIRD ***

WATCHBIRD

By ROBERT SHECKLEY

Illustrated by EMSH

Strange how often the Millennium has been at

hand. The idea is peace on Earth, see, and

the way to do it is by figuring out angles.

When Gelsen entered, he

saw that the rest of

the watchbird manufacturers

were already present.

There were six of them, not

counting himself, and the room

was blue with expensive cigar

smoke.

"Hi, Charlie," one of them

called as he came in.

The rest broke off conversation

long enough to wave a casual

greeting at him. As a

watchbird manufacturer, he was

a member manufacturer of salvation,

he reminded himself wryly.

Very exclusive. You must have a

certified government contract if

you want to save the human

race.

"The government representative

isn't here yet," one of the

men told him. "He's due any

minute."

"We're getting the green

light," another said.

"Fine." Gelsen found a chair

near the door and looked around

the room. It was like a convention,

or a Boy Scout rally. The

six men made up for their lack

of numbers by sheer volume. The

president of Southern Consolidated

was talking at the top of his

lungs about watchbird's enormous

durability. The two presidents

he was talking at were

grinning, nodding, one trying to

interrupt with the results of a

test he had run on watchbird's

resourcefulness, the other talking

about the new recharging apparatus.

The other three men were in

their own little group, delivering

what sounded like a panegyric

to watchbird.

Gelsen noticed that all of them

stood straight and tall, like the

saviors they felt they were. He

didn't find it funny. Up to a few

days ago he had felt that way

himself. He had considered himself

a pot-bellied, slightly balding

saint.

He sighed and lighted a cigarette.

At the beginning of the

project, he had been as enthusiastic

as the others. He remembered

saying to Macintyre, his

chief engineer, "Mac, a new day

is coming. Watchbird is the Answer."

And Macintyre had nodded

very profoundly—another

watchbird convert.

How wonderful it had seemed

then! A simple, reliable answer

to one of mankind's greatest

problems, all wrapped and packaged

in a pound of incorruptible

metal, crystal and plastics.

Perhaps that was the very reason

he was doubting it now. Gelsen

suspected that you don't

solve human problems so easily.

There had to be a catch somewhere.

After all, murder was an old

problem, and watchbird too new

a solution.

"Gentlemen—" They had been

talking so heatedly that they

hadn't noticed the government

representative entering. Now the

room became quiet at once.

"Gentlemen," the plump government

man said, "the President,

with the consent of

Congress, has acted to form a

watchbird division for every city

and town in the country."

The men burst into a spontaneous

shout of triumph. They

were going to have their chance

to save the world after all, Gelsen

thought, and worriedly asked

himself what was wrong with

that.

He listened carefully as the

government man outlined the

distribution scheme. The country

was to be divided into seven

areas, each to be supplied and

serviced by one manufacturer.

This meant monopoly, of course,

but a necessary one. Like the

telephone service, it was in

the public's best interests. You

couldn't have competition in

watchbird service. Watchbird

was for everyone.

"The President hopes," the

representative continued, "that

full watchbird service will be installed

in the shortest possible

time. You will have top priorities

on strategic metals, manpower,

and so forth."

"Speaking for myself," the

president of Southern Consolidated

said, "I expect to have the

first batch of watchbirds distributed

within the week. Production

is all set up."

The rest of the men were

equally ready. The factories

had been prepared to roll out

the watchbirds for months now.

The final standardized equipment

had been agreed upon, and

only the Presidential go-ahead

had been lacking.

"Fine," the representative said.

"If that is all, I think we can—is

there a question?"

"Yes, sir," Gelsen said. "I

want to know if the present model

is the one we are going to manufacture."

"Of course," the representative

said. "It's the most advanced."

"I have an objection." Gelsen

stood up. His colleagues were

glaring coldly at him. Obviously

he was delaying the advent of

the golden age.

"What is your objection?" the

representative asked.

"First, let me say that I am

one hundred per cent in favor of

a machine to stop murder. It's

been needed for a long time. I

object only to the watchbird's

learning circuits. They serve, in

effect, to animate the machine

and give it a pseudo-consciousness.

I can't approve of that."

"But, Mr. Gelsen, you yourself

testified that the watchbird would

not be completely efficient unless

such circuits were introduced.

Without them, the watchbirds

could stop only an estimated

seventy per cent of murders."

"I know that," Gelsen said,

feeling extremely uncomfortable.

"I believe there might be a moral

danger in allowing a machine to

make decisions that are rightfully

Man's," he declared doggedly.

"Oh, come now, Gelsen," one

of the corporation presidents said.

"It's nothing of the sort. The

watchbird will only reinforce the

decisions made by honest men

from the beginning of time."

"I think that is true," the representative

agreed. "But I can

understand how Mr. Gelsen feels.

It is sad that we must put a human

problem into the hands of a

machine, sadder still that we

must have a machine enforce our

laws. But I ask you to remember,

Mr. Gelsen, that there is no

other possible way of stopping a

murderer before he strikes. It

would be unfair to the many innocent

people killed every year

if we were to restrict watchbird

on philosophical grounds. Don't

you agree that I'm right?"

"Yes, I suppose I do," Gelsen

said unhappily. He had told himself

all that a thousand times,

but something still bothered him.

Perhaps he would talk it over

with Macintyre.

As the conference broke up, a

thought struck him. He grinned.

A lot of policemen were going

to be out of work!

"Now what do you think

of that?" Officer Celtrics

demanded. "Fifteen years in Homicide

and a machine is replacing

me." He wiped a large red

hand across his forehead and

leaned against the captain's desk.

"Ain't science marvelous?"

Two other policemen, late of

Homicide, nodded glumly.

"Don't worry about it," the

captain said. "We'll find a home

for you in Larceny, Celtrics.

You'll like it here."

"I just can't get over it," Celtrics

complained. "A lousy little

piece of tin and glass is going

to solve all the crimes."

"Not quite," the captain said.

"The watchbirds are supposed

to prevent the crimes before they

happen."

"Then how'll they be crimes?"

one of the policeman asked. "I

mean they can't hang you for

murder until you commit one,

can they?"

"That's not the idea," the captain

said. "The watchbirds are

supposed to stop a man before

he commits a murder."

"Then no one arrests him?"

Celtrics asked.

"I don't know how they're going

to work that out," the captain

admitted.

The men were silent for a

while. The captain yawned and

examined his watch.

"The thing I don't understand,"

Celtrics said, still leaning

on the captain's desk, "is just

how do they do it? How did it

start, Captain?"

The captain studied Celtrics'

face for possible irony; after

all, watchbird had been in the

papers for months. But then he

remembered that Celtrics, like

his sidekicks, rarely bothered to

turn past the sports pages.

"Well," the captain said, trying

to remember what he had

read in the Sunday supplements,

"these scientists were working on

criminology. They were studying

murderers, to find out what made

them tick. So they found that

murderers throw out a different

sort of brain wave from ordinary

people. And their glands act

funny, too. All this happens

when they're about to commit a

murder. So these scientists worked

out a special machine to flash

red or something when these

brain waves turned on."

"Scientists," Celtrics said bitterly.

"Well, after the scientists had

this machine, they didn't know

what to do with it. It was too

big to move around, and murderers

didn't drop in often enough

to make it flash. So they built it

into a smaller unit and tried it

out in a few police stations. I

think they tried one upstate. But

it didn't work so good. You

couldn't get to the crime in time.

That's why they built the watchbirds."

"I don't think they'll stop no

criminals," one of the policemen

insisted.

"They sure will. I read the

test results. They can smell him

out before he commits a crime.

And when they reach him, they

give him a powerful shock or

something. It'll stop him."

"You closing up Homicide,

Captain?" Celtrics asked.

"Nope," the captain said. "I'm

leaving a skeleton crew in until

we see how these birds do."

"Hah," Celtrics said. "Skeleton

crew. That's funny."

"Sure," the captain said. "Anyhow,

I'm going to leave some men

on. It seems the birds don't stop

all murders."

"Why not?"

"Some murderers don't have

these brain waves," the captain

answered, trying to remember

what the newspaper article had

said. "Or their glands don't work

or something."

"Which ones don't they stop?"

Celtrics asked, with professional

curiosity.

"I don't know. But I hear they

got the damned things fixed so

they're going to stop all of them

soon."

"How they working that?"

"They learn. The watchbirds,

I mean. Just like people."

"You kidding me?"

"Nope."

"Well," Celtrics said, "I think

I'll just keep old Betsy oiled,

just in case. You can't trust these

scientists."

"Right."

"Birds!" Celtrics scoffed.

Over the town, the watchbird

soared in a long, lazy curve.

Its aluminum hide glistened in

the morning sun, and dots of

light danced on its stiff wings.

Silently it flew.

Silently, but with all senses

functioning. Built-in kinesthetics

told the watchbird where it was,

and held it in a long search curve.

Its eyes and ears operated as one

unit, searching, seeking.

And then something happened!

The watchbird's electronically

fast reflexes picked up the edge

of a sensation. A correlation center

tested it, matching it with

electrical and chemical data in

its memory files. A relay tripped.

Down the watchbird spiraled,

coming in on the increasingly

strong sensation. It smelled the

outpouring of certain glands,

tasted a deviant brain wave.

Fully alerted and armed, it

spun and banked in the bright

morning sunlight.

Dinelli was so intent he didn't

see the watchbird coming. He

had his gun poised, and his eyes

pleaded with the big grocer.

"Don't come no closer."

"You lousy little punk," the

grocer said, and took another

step forward. "Rob me? I'll break

every bone in your puny body."

The grocer, too stupid or too

courageous to understand the

threat of the gun, advanced on

the little thief.

"All right," Dinelli said, in a

thorough state of panic. "All

right, sucker, take—"

A bolt of electricity knocked

him on his back. The gun went

off, smashing a breakfast food

display.

"What in hell?" the grocer

asked, staring at the stunned

thief. And then he saw a flash

of silver wings. "Well, I'm really

damned. Those watchbirds work!"

He stared until the wings disappeared

in the sky. Then he

telephoned the police.

The watchbird returned to his

search curve. His thinking center

correlated the new facts he had

learned about murder. Several of

these he hadn't known before.

This new information was simultaneously

flashed to all the

other watchbirds and their information

was flashed back to

him.

New information, methods, definitions

were constantly passing

between them.

Now that the watchbirds were

rolling off the assembly line

in a steady stream, Gelsen allowed

himself to relax. A loud

contented hum filled his plant.

Orders were being filled on time,

with top priorities given to the

biggest cities in his area, and

working down to the smallest

towns.

"All smooth, Chief," Macintyre

said, coming in the door. He had

just completed a routine inspection.

"Fine. Have a seat."

The big engineer sat down and

lighted a cigarette.

"We've been working on this

for some time," Gelsen said, when

he couldn't think of anything

else.

"We sure have," Macintyre

agreed. He leaned back and inhaled

deeply. He had been one

of the consulting engineers on

the original watchbird. That was

six years back. He had been

working for Gelsen ever since,

and the men had become good

friends.

"The thing I wanted to ask

you was this—" Gelsen paused.

He couldn't think how to phrase

what he wanted. Instead he asked,

"What do you think of the

watchbirds, Mac?"

"Who, me?" The engineer

grinned nervously. He had been

eating, drinking and sleeping

watchbird ever since its inception.

He had never found it necessary

to have an attitude. "Why,

I think it's great."

"I don't mean that," Gelsen

said. He realized that what he

wanted was to have someone understand

his point of view. "I

mean do you figure there might

be some danger in machine

thinking?"

"I don't think so, Chief. Why

do you ask?"

"Look, I'm no scientist or engineer.

I've just handled cost and

production and let you boys

worry about how. But as a layman,

watchbird is starting to

frighten me."

"No reason for that."

"I don't like the idea of the

learning circuits."

"But why not?" Then Macintyre

grinned again. "I know.

You're like a lot of people, Chief—afraid

your machines are going

to wake up and say, 'What are

we doing here? Let's go out and

rule the world.' Is that it?"

"Maybe something like that,"

Gelsen admitted.

"No chance of it," Macintyre

said. "The watchbirds are complex,

I'll admit, but an M.I.T.

calculator is a whole lot more

complex. And it hasn't got consciousness."

"No. But the watchbirds can

learn."

"Sure. So can all the new calculators.

Do you think they'll

team up with the watchbirds?"

Gelsen felt annoyed at Macintyre,

and even more annoyed

at himself for being ridiculous.

"It's a fact that the

watchbirds can put their learning

into action. No one is monitoring

them."

"So that's the trouble," Macintyre

said.

"I've been thinking of getting

out of watchbird." Gelsen hadn't

realized it until that moment.

"Look, Chief," Macintyre said.

"Will you take an engineer's word

on this?"

"Let's hear it."

"The watchbirds are no more

dangerous than an automobile,

an IBM calculator or a thermometer.

They have no more consciousness

or volition than those

things. The watchbirds are built

to respond to certain stimuli, and

to carry out certain operations

when they receive that stimuli."

"And the learning circuits?"

"You have to have those,"

Macintyre said patiently, as

though explaining the whole

thing to a ten-year-old. "The

purpose of the watchbird is to

frustrate all murder-attempts,

right? Well, only certain murderers

give out these stimuli. In

order to stop all of them, the

watchbird has to search out new

definitions of murder and correlate

them with what it already

knows."

"I think it's inhuman," Gelsen

said.

"That's the best thing about

it. The watchbirds are unemotional.

Their reasoning is non-anthropomorphic.

You can't

bribe them or drug them. You

shouldn't fear them, either."

The intercom on Gelsen's desk

buzzed. He ignored it.

"I know all this," Gelsen said.

"But, still, sometimes I feel like

the man who invented dynamite.

He thought it would only be

used for blowing up tree stumps."

"You didn't invent watchbird."

"I still feel morally responsible

because I manufacture them."

The intercom buzzed again,

and Gelsen irritably punched a

button.

"The reports are in on the first

week of watchbird operation,"

his secretary told him.

"How do they look?"

"Wonderful, sir."

"Send them in in fifteen minutes."

Gelsen switched the intercom

off and turned back to

Macintyre, who was cleaning his

fingernails with a wooden match.

"Don't you think that this represents

a trend in human thinking?

The mechanical god? The electronic

father?"

"Chief," Macintyre said, "I

think you should study watchbird

more closely. Do you know

what's built into the circuits?"

"Only generally."

"First, there is a purpose.

Which is to stop living organisms

from committing murder. Two,

murder may be defined as an

act of violence, consisting of

breaking, mangling, maltreating

or otherwise stopping the functions

of a living organism by a

living organism. Three, most

murderers are detectable by certain

chemical and electrical

changes."

Macintyre paused to light another

cigarette. "Those conditions

take care of the routine functions.

Then, for the learning

circuits, there are two more

conditions. Four, there are some

living organisms who commit

murder without the signs mentioned

in three. Five, these can be

detected by data applicable to

condition two."

"I see," Gelsen said.

"You realize how foolproof it

is?"

"I suppose so." Gelsen hesitated

a moment. "I guess that's

all."

"Right," the engineer said, and

left.

Gelsen thought for a few moments.

There couldn't be anything

wrong with the watchbirds.

"Send in the reports," he said

into the intercom.

High above the lighted buildings

of the city, the watchbird

soared. It was dark, but in

the distance the watchbird could

see another, and another beyond

that. For this was a large city.

To prevent murder ...

There was more to watch for

now. New information had

crossed the invisible network that

connected all watchbirds. New

data, new ways of detecting the

violence of murder.

There! The edge of a sensation!

Two watchbirds dipped simultaneously.

One had received

the scent a fraction of a second

before the other. He continued

down while the other resumed

monitoring.

Condition four, there are some

living organisms who commit

murder without the signs mentioned

in condition three.

Through his new information,

the watchbird knew by extrapolation

that this organism was

bent on murder, even though the

characteristic chemical and electrical

smells were absent.

The watchbird, all senses

acute, closed in on the organism.

He found what he wanted, and

dived.

Roger Greco leaned against a

building, his hands in his pockets.

In his left hand was the cool butt

of a .45. Greco waited patiently.

He wasn't thinking of anything

in particular, just relaxing against

a building, waiting for a man.

Greco didn't know why the man

was to be killed. He didn't care.

Greco's lack of curiosity was part

of his value. The other part was

his skill.

One bullet, neatly placed in

the head of a man he didn't

know. It didn't excite him or

sicken him. It was a job, just like

anything else. You killed a man.

So?

As Greco's victim stepped out

of a building, Greco lifted the

.45 out of his pocket. He released

the safety and braced the gun

with his right hand. He still

wasn't thinking of anything as

he took aim ...

And was knocked off his feet.

Greco thought he had been

shot. He struggled up again,

looked around, and sighted foggily

on his victim.

Again he was knocked down.

This time he lay on the ground,

trying to draw a bead. He never

thought of stopping, for Greco

was a craftsman.

With the next blow, everything

went black. Permanently, because

the watchbird's duty was

to protect the object of violence—at

whatever cost to the murderer.

The victim walked to his car.

He hadn't noticed anything unusual.

Everything had happened

in silence.

Gelsen was feeling pretty

good. The watchbirds had

been operating perfectly. Crimes

of violence had been cut in half,

and cut again. Dark alleys were

no longer mouths of horror.

Parks and playgrounds were not

places to shun after dusk.

Of course, there were still robberies.

Petty thievery flourished,

and embezzlement, larceny, forgery

and a hundred other crimes.

But that wasn't so important.

You could regain lost money—never

a lost life.

Gelsen was ready to admit that

he had been wrong about the

watchbirds. They were doing a

job that humans had been unable

to accomplish.

The first hint of something

wrong came that morning.

Macintyre came into his office.

He stood silently in front of

Gelsen's desk, looking annoyed

and a little embarrassed.

"What's the matter, Mac?"

Gelsen asked.

"One of the watchbirds went

to work on a slaughterhouse man.

Knocked him out."

Gelsen thought about it for a

moment. Yes, the watchbirds

would do that. With their new

learning circuits, they had probably

defined the killing of animals

as murder.

"Tell the packers to mechanize

their slaughtering," Gelsen

said. "I never liked that business

myself."

"All right," Macintyre said.

He pursed his lips, then shrugged

his shoulders and left.

Gelsen stood beside his desk,

thinking. Couldn't the watchbirds

differentiate between a

murderer and a man engaged in

a legitimate profession? No, evidently

not. To them, murder was

murder. No exceptions. He

frowned. That might take a little

ironing out in the circuits.

But not too much, he decided

hastily. Just make them a little

more discriminating.

He sat down again and buried

himself in paperwork, trying to

avoid the edge of an old fear.

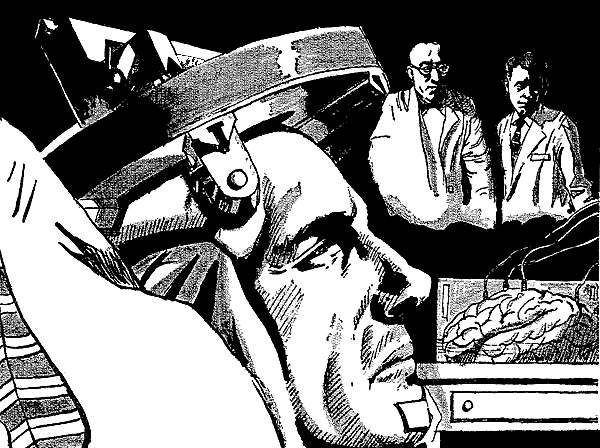

They strapped the prisoner

into the chair and fitted the

electrode to his leg.

"Oh, oh," he moaned, only

half-conscious now of what they

were doing.

They fitted the helmet over his

shaved head and tightened the

last straps. He continued to moan

softly.

And then the watchbird swept

in. How he had come, no one

knew. Prisons are large and

strong, with many locked doors,

but the watchbird was there—

To stop a murder.

"Get that thing out of here!"

the warden shouted, and reached

for the switch. The watchbird

knocked him down.

"Stop that!" a guard screamed,

and grabbed for the switch himself.

He was knocked to the floor

beside the warden.

"This isn't murder, you idiot!"

another guard said. He drew his

gun to shoot down the glittering,

wheeling metal bird.

Anticipating, the watchbird

smashed him back against the

wall.

There was silence in the room.

After a while, the man in the

helmet started to giggle. Then

he stopped.

The watchbird stood on guard,

fluttering in mid-air—

Making sure no murder was

done.

New data flashed along the

watchbird network. Unmonitored,

independent, the thousands

of watchbirds received and acted

upon it.

The breaking, mangling or

otherwise stopping the functions

of a living organism by a living

organism. New acts to stop.

"Damn you, git going!" Farmer

Ollister shouted, and raised his

whip again. The horse balked,

and the wagon rattled and shook

as he edged sideways.

"You lousy hunk of pigmeal,

git going!" the farmer yelled and

he raised the whip again.

It never fell. An alert watchbird,

sensing violence, had knocked

him out of his seat.

A living organism? What is a

living organism? The watchbirds

extended their definitions as they

became aware of more facts. And,

of course, this gave them more

work.

The deer was just visible at the

edge of the woods. The hunter

raised his rifle, and took careful

aim.

He didn't have time to shoot.

With his free hand, Gelsen

mopped perspiration from

his face. "All right," he said into

the telephone. He listened to the

stream of vituperation from the

other end, then placed the receiver

gently in its cradle.

"What was that one?" Macintyre

asked. He was unshaven, tie

loose, shirt unbuttoned.

"Another fisherman," Gelsen

said. "It seems the watchbirds

won't let him fish even though

his family is starving. What are

we going to do about it, he wants

to know."

"How many hundred is that?"

"I don't know. I haven't opened

the mail."

"Well, I figured out where the

trouble is," Macintyre said

gloomily, with the air of a man

who knows just how he blew up

the Earth—after it was too late.

"Let's hear it."

"Everybody took it for granted

that we wanted all murder

stopped. We figured the watchbirds

would think as we do. We

ought to have qualified the conditions."

"I've got an idea," Gelsen

said, "that we'd have to know

just why and what murder is,

before we could qualify the conditions

properly. And if we knew

that, we wouldn't need the watchbirds."

"Oh, I don't know about that.

They just have to be told that

some things which look like murder

are not murder."

"But why should they stop

fisherman?" Gelsen asked.

"Why shouldn't they? Fish and

animals are living organisms. We

just don't think that killing them

is murder."

The telephone rang. Gelsen

glared at it and punched the intercom.

"I told you no more

calls, no matter what."

"This is from Washington,"

his secretary said. "I thought

you'd—"

"Sorry." Gelsen picked up the

telephone. "Yes. Certainly is a

mess ... Have they? All right, I

certainly will." He put down the

telephone.

"Short and sweet," he told

Macintyre. "We're to shut down

temporarily."

"That won't be so easy," Macintyre

said. "The watchbirds

operate independent of any central

control, you know. They

come back once a week for a

repair checkup. We'll have to

turn them off then, one by one."

"Well, let's get to it. Monroe

over on the Coast has shut down

about a quarter of his birds."

"I think I can dope out a restricting

circuit," Macintyre said.

"Fine," Gelsen replied bitterly.

"You make me very happy."

The watchbirds were learning

rapidly, expanding and adding

to their knowledge. Loosely defined

abstractions were extended,

acted upon and re-extended.

To stop murder ...

Metal and electrons reason

well, but not in a human fashion.

A living organism? Any living

organism!

The watchbirds set themselves

the task of protecting all living

things.

The fly buzzed around the

room, lighting on a table top,

pausing a moment, then darting

to a window sill.

The old man stalked it, a rolled

newspaper in his hand.

Murderer!

The watchbirds swept down

and saved the fly in the nick of

time.

The old man writhed on the

floor a minute and then was silent.

He had been given only a

mild shock, but it had been

enough for his fluttery, cranky

heart.

His victim had been saved,

though, and this was the important

thing. Save the victim and

give the aggressor his just desserts.

Gelsen demanded angrily,

"Why aren't they being

turned off?"

The assistant control engineer

gestured. In a corner of the repair

room lay the senior control

engineer. He was just regaining

consciousness.

"He tried to turn one of them

off," the assistant engineer said.

Both his hands were knotted together.

He was making a visible

effort not to shake.

"That's ridiculous. They

haven't got any sense of self-preservation."

"Then turn them off yourself.

Besides, I don't think any more

are going to come."

What could have happened?

Gelsen began to piece it together.

The watchbirds still hadn't decided

on the limits of a living

organism. When some of them

were turned off in the Monroe

plant, the rest must have correlated

the data.

So they had been forced to

assume that they were living

organisms, as well.

No one had ever told them

otherwise. Certainly they carried

on most of the functions of living

organisms.

Then the old fears hit him.

Gelsen trembled and hurried out

of the repair room. He wanted

to find Macintyre in a hurry.

The nurse handed the surgeon

the sponge.

"Scalpel."

She placed it in his hand. He

started to make the first incision.

And then he was aware of a disturbance.

"Who let that thing in?"

"I don't know," the nurse said,

her voice muffled by the mask.

"Get it out of here."

The nurse waved her arms at

the bright winged thing, but it

fluttered over her head.

The surgeon proceeded with

the incision—as long as he was

able.

The watchbird drove him away

and stood guard.

"Telephone the watchbird

company!" the surgeon ordered.

"Get them to turn the thing off."

The watchbird was preventing

violence to a living organism.

The surgeon stood by helplessly

while his patient died.

Fluttering high above the

network of highways, the

watchbird watched and waited.

It had been constantly working

for weeks now, without rest or

repair. Rest and repair were impossible,

because the watchbird

couldn't allow itself—a living organism—to

be murdered. And

that was what happened when

watchbirds returned to the factory.

There was a built-in order to

return, after the lapse of a certain

time period. But the watchbird

had a stronger order to obey—preservation

of life, including

its own.

The definitions of murder

were almost infinitely extended

now, impossible to cope with.

But the watchbird didn't consider

that. It responded to its stimuli,

whenever they came and whatever

their source.

There was a new definition of

living organism in its memory

files. It had come as a result of

the watchbird discovery that

watchbirds were living organisms.

And it had enormous ramifications.

The stimuli came! For the

hundredth time that day, the bird

wheeled and banked, dropping

swiftly down to stop murder.

Jackson yawned and pulled his

car to a shoulder of the road.

He didn't notice the glittering

dot in the sky. There was no reason

for him to. Jackson wasn't

contemplating murder, by any

human definition.

This was a good spot for a

nap, he decided. He had been

driving for seven straight hours

and his eyes were starting to fog.

He reached out to turn off the

ignition key—

And was knocked back against

the side of the car.

"What in hell's wrong with

you?" he asked indignantly. "All

I want to do is—" He reached

for the key again, and again he

was smacked back.

Jackson knew better than to

try a third time. He had been

listening to the radio and he knew

what the watchbirds did to stubborn

violators.

"You mechanical jerk," he

said to the waiting metal bird.

"A car's not alive. I'm not trying

to kill it."

But the watchbird only knew

that a certain operation resulted

in stopping an organism. The car

was certainly a functioning organism.

Wasn't it of metal, as

were the watchbirds? Didn't it

run?

Macintyre said, "Without

repairs they'll run down."

He shoved a pile of specification

sheets out of his way.

"How soon?" Gelsen asked.

"Six months to a year. Say a

year, barring accidents."

"A year," Gelsen said. "In the

meantime, everything is stopping

dead. Do you know the latest?"

"What?"

"The watchbirds have decided

that the Earth is a living organism.

They won't allow farmers

to break ground for plowing.

And, of course, everything else is

a living organism—rabbits, beetles,

flies, wolves, mosquitoes,

lions, crocodiles, crows, and smaller

forms of life such as bacteria."

"I know," Macintyre said.

"And you tell me they'll wear

out in six months or a year. What

happens now? What are we going

to eat in six months?"

The engineer rubbed his chin.

"We'll have to do something

quick and fast. Ecological balance

is gone to hell."

"Fast isn't the word. Instantaneously

would be better." Gelsen

lighted his thirty-fifth

cigarette for the day. "At least I

have the bitter satisfaction of

saying, 'I told you so.' Although

I'm just as responsible as the

rest of the machine-worshipping

fools."

Macintyre wasn't listening. He

was thinking about watchbirds.

"Like the rabbit plague in Australia."

"The death rate is mounting,"

Gelsen said. "Famine. Floods.

Can't cut down trees. Doctors

can't—what was that you

said about Australia?"

"The rabbits," Macintyre repeated.

"Hardly any left in Australia

now."

"Why? How was it done?"

"Oh, found some kind of germ

that attacked only rabbits. I

think it was propagated by mosquitos—"

"Work on that," Gelsen said.

"You might have something. I

want you to get on the telephone,

ask for an emergency hookup

with the engineers of the other

companies. Hurry it up. Together

you may be able to dope out

something."

"Right," Macintyre said. He

grabbed a handful of blank paper

and hurried to the telephone.

"What did I tell you?" Officer

Celtrics said. He

grinned at the captain. "Didn't I

tell you scientists were nuts?"

"I didn't say you were wrong,

did I?" the captain asked.

"No, but you weren't sure."

"Well, I'm sure now. You'd

better get going. There's plenty

of work for you."

"I know." Celtrics drew his

revolver from its holster, checked

it and put it back. "Are all the

boys back, Captain?"

"All?" the captain laughed humorlessly.

"Homicide has increased

by fifty per cent. There's

more murder now than there's

ever been."

"Sure," Celtrics said. "The

watchbirds are too busy guarding

cars and slugging spiders."

He started toward the door, then

turned for a parting shot.

"Take my word, Captain. Machines

are stupid."

The captain nodded.

Thousands of watchbirds,

trying to stop countless millions

of murders—a hopeless

task. But the watchbirds didn't

hope. Without consciousness, they

experienced no sense of accomplishment,

no fear of failure. Patiently

they went about their

jobs, obeying each stimulus as it

came.

They couldn't be everywhere

at the same time, but it wasn't

necessary to be. People learned

quickly what the watchbirds

didn't like and refrained from doing

it. It just wasn't safe. With

their high speed and superfast

senses, the watchbirds got around

quickly.

And now they meant business.

In their original directives there

had been a provision made for

killing a murderer, if all other

means failed.

Why spare a murderer?

It backfired. The watchbirds

extracted the fact that murder

and crimes of violence had increased

geometrically since they

had begun operation. This was

true, because their new definitions

increased the possibilities of murder.

But to the watchbirds, the

rise showed that the first methods

had failed.

Simple logic. If A doesn't work,

try B. The watchbirds shocked

to kill.

Slaughterhouses in Chicago

stopped and cattle starved to

death in their pens, because

farmers in the Midwest couldn't

cut hay or harvest grain.

No one had told the watchbirds

that all life depends on carefully

balanced murders.

Starvation didn't concern the

watchbirds, since it was an act

of omission.

Their interest lay only in acts

of commission.

Hunters sat home, glaring at

the silver dots in the sky, longing

to shoot them down. But for

the most part, they didn't try.

The watchbirds were quick to

sense the murder intent and to

punish it.

Fishing boats swung idle at

their moorings in San Pedro and

Gloucester. Fish were living organisms.

Farmers cursed and spat and

died, trying to harvest the crop.

Grain was alive and thus worthy

of protection. Potatoes were as

important to the watchbird as

any other living organism. The

death of a blade of grass was

equal to the assassination of a

President—

To the watchbirds.

And, of course, certain machines

were living. This followed,

since the watchbirds were machines

and living.

God help you if you maltreated

your radio. Turning it off meant

killing it. Obviously—its voice

was silenced, the red glow of its

tubes faded, it grew cold.

The watchbirds tried to guard

their other charges. Wolves were

slaughtered, trying to kill rabbits.

Rabbits were electrocuted,

trying to eat vegetables. Creepers

were burned out in the act of

strangling trees.

A butterfly was executed,

caught in the act of outraging a

rose.

This control was spasmodic,

because of the fewness of the

watchbirds. A billion watchbirds

couldn't have carried out the ambitious

project set by the thousands.

The effect was of a murderous

force, ten thousand bolts of irrational

lightning raging around the

country, striking a thousand

times a day.

Lightning which anticipated

your moves and punished your

intentions.

"Gentlemen, please," the

government representative

begged. "We must hurry."

The seven manufacturers stopped

talking.

"Before we begin this meeting

formally," the president of Monroe

said, "I want to say something.

We do not feel ourselves

responsible for this unhappy

state of affairs. It was a government

project; the government

must accept the responsibility,

both moral and financial."

Gelsen shrugged his shoulders.

It was hard to believe that these

men, just a few weeks ago, had

been willing to accept the glory

of saving the world. Now they

wanted to shrug off the responsibility

when the salvation went

amiss.

"I'm positive that that need

not concern us now," the representative

assured him. "We must

hurry. You engineers have done

an excellent job. I am proud of

the cooperation you have shown

in this emergency. You are hereby

empowered to put the outlined

plan into action."

"Wait a minute," Gelsen said.

"There is no time."

"The plan's no good."

"Don't you think it will work?"

"Of course it will work. But

I'm afraid the cure will be worse

than the disease."

The manufacturers looked as

though they would have enjoyed

throttling Gelsen. He didn't hesitate.

"Haven't we learned yet?" he

asked. "Don't you see that you

can't cure human problems by

mechanization?"

"Mr. Gelsen," the president of

Monroe said, "I would enjoy

hearing you philosophize, but, unfortunately,

people are being

killed. Crops are being ruined.

There is famine in some sections

of the country already. The

watchbirds must be stopped at

once!"

"Murder must be stopped, too.

I remember all of us agreeing

upon that. But this is not the

way!"

"What would you suggest?"

the representative asked.

Gelsen took a deep breath.

What he was about to say

took all the courage he had.

"Let the watchbirds run down

by themselves," Gelsen suggested.

There was a near-riot. The

government representative broke

it up.

"Let's take our lesson," Gelsen

urged, "admit that we were

wrong trying to cure human

problems by mechanical means.

Start again. Use machines, yes,

but not as judges and teachers

and fathers."

"Ridiculous," the representative

said coldly. "Mr. Gelsen,

you are overwrought. I suggest

you control yourself." He cleared

his throat. "All of you are ordered

by the President to carry

out the plan you have submitted."

He looked sharply at Gelsen.

"Not to do so will be treason."

"I'll cooperate to the best of

my ability," Gelsen said.

"Good. Those assembly lines

must be rolling within the week."

Gelsen walked out of the room

alone. Now he was confused

again. Had he been right or was

he just another visionary? Certainly,

he hadn't explained himself

with much clarity.

Did he know what he meant?

Gelsen cursed under his breath.

He wondered why he couldn't

ever be sure of anything. Weren't

there any values he could hold

on to?

He hurried to the airport and

to his plant.

The watchbird was operating

erratically now. Many of its

delicate parts were out of line,

worn by almost continuous operation.

But gallantly it responded

when the stimuli came.

A spider was attacking a fly.

The watchbird swooped down

to the rescue.

Simultaneously, it became

aware of something overhead.

The watchbird wheeled to meet

it.

There was a sharp crackle and

a power bolt whizzed by the

watchbird's wing. Angrily, it

spat a shock wave.

The attacker was heavily insulated.

Again it spat at the watchbird.

This time, a bolt smashed

through a wing, the watchbird

darted away, but the attacker

went after it in a burst of speed,

throwing out more crackling

power.

The watchbird fell, but managed

to send out its message.

Urgent! A new menace to living

organisms and this was the deadliest

yet!

Other watchbirds around the

country integrated the message.

Their thinking centers searched

for an answer.

"Well, Chief, they bagged

fifty today," Macintyre

said, coming into Gelsen's office.

"Fine," Gelsen said, not looking

at the engineer.

"Not so fine." Macintyre sat

down. "Lord, I'm tired! It was

seventy-two yesterday."

"I know." On Gelsen's desk

were several dozen lawsuits,

which he was sending to the government

with a prayer.

"They'll pick up again,

though," Macintyre said confidently.

"The Hawks are especially

built to hunt down watchbirds.

They're stronger, faster, and

they've got better armor. We really

rolled them out in a hurry,

huh?"

"We sure did."

"The watchbirds are pretty

good, too," Macintyre had to

admit. "They're learning to take

cover. They're trying a lot of

stunts. You know, each one that

goes down tells the others something."

Gelsen didn't answer.

"But anything the watchbirds

can do, the Hawks can do better,"

Macintyre said cheerfully.

"The Hawks have special learning

circuits for hunting. They're

more flexible than the watchbirds.

They learn faster."

Gelsen gloomily stood up,

stretched, and walked to the window.

The sky was blank. Looking

out, he realized that his

uncertainties were over. Right or

wrong, he had made up his mind.

"Tell me," he said, still watching

the sky, "what will the

Hawks hunt after they get all the

watchbirds?"

"Huh?" Macintyre said.

"Why—"

"Just to be on the safe side,

you'd better design something to

hunt down the Hawks. Just in

case, I mean."

"You think—"

"All I know is that the Hawks

are self-controlled. So were the

watchbirds. Remote control

would have been too slow, the

argument went on. The idea was

to get the watchbirds and get

them fast. That meant no restricting

circuits."

"We can dope something out,"

Macintyre said uncertainly.

"You've got an aggressive machine

up in the air now. A murder

machine. Before that it was

an anti-murder machine. Your

next gadget will have to be even

more self-sufficient, won't it?"

Macintyre didn't answer.

"I don't hold you responsible,"

Gelsen said. "It's me. It's everyone."

In the air outside was a swift-moving

dot.

"That's what comes," said Gelsen,

"of giving a machine the

job that was our own responsibility."

Overhead, a Hawk was

zeroing in on a watchbird.

The armored murder machine

had learned a lot in a few days.

Its sole function was to kill. At

present it was impelled toward a

certain type of living organism,

metallic like itself.

But the Hawk had just discovered

that there were other

types of living organisms, too—

Which had to be murdered.

—ROBERT SHECKLEY

Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Galaxy Science Fiction February 1953.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S.

copyright on this publication was renewed. Minor spelling and

typographical errors have been corrected without note.