The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Princess of the School

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: The Princess of the School

Author: Angela Brazil

Illustrator: Frank Wiles

Release date: June 1, 2007 [eBook #21656]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jana Srna, Suzanne Shell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PRINCESS OF THE SCHOOL ***

"i've come to say good-by to you, sis"

THE PRINCESS

OF THE SCHOOL

By ANGELA BRAZIL

Author of

"The Luckiest Girl in the School,"

"The Harum-Scarum Schoolgirl,"

"A Popular Schoolgirl,"

"The Head Girl at the Gables."

Illustrated by Frank Wiles.

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

Published by arrangement with Frederick A. Stokes Company

Printed in U. S. A.

Copyright, 1920, by

Frederick A. Stokes Company

All rights reserved

First published in the United States of America, 1921

Contents

| chapter | page | |

|---|---|---|

| I | The Ingleton Family | 1 |

| II | A Stolen Joy-ride | 15 |

| III | A Valentine Party | 33 |

| IV | Disinherited | 50 |

| V | The New Owner | 61 |

| VI | Princess Carmel | 73 |

| VII | An Old Greek Idyll | 88 |

| VIII | Wood Nymphs | 100 |

| IX | The Open Road | 114 |

| X | A Meeting | 129 |

| XI | A Secret Society | 145 |

| XII | White Magic | 157 |

| XIII | The Money-makers | 171 |

| XIV | All in a Mist | 190 |

| XV | On the High Seas | 201 |

| XVI | The Casa Bianca | 215 |

| XVII | Sicilian Cousins | 229 |

| XVIII | A Night of Adventure | 242 |

| XIX | At Palermo | 261 |

| XX | Old England | 271 |

| XXI | Carmel's Kingdom | 283 |

THE PRINCESS OF THE SCHOOL

chapter i

The Ingleton Family

On a certain morning, just a week before[1]

Christmas, the little world of school at Chilcombe

Hall was awake and stirring at an unusually

early hour. Long before the slightest hint of

dawn showed in the sky the lamps were lighted

in the corridors, maids were scuttling about,

bringing in breakfast, and Jones, the gardener,

assisted by his eldest boy, a sturdy grinning

urchin of twelve, was beginning the process of

carrying down piles of hand-bags and hold-alls,

and stacking them on a cart which was waiting in

the drive outside.

Miss Walters, dreading the Christmas rush on

the railway, had determined to take time by the

forelock, and meant to pack off her pupils by the

first available trains, trusting they would most of

them reach their destinations before the overcrowding

became a serious problem in the traffic.[2]

The pupils themselves offered no objections to

this early start. The sooner they reached home

and began the holidays, so much the better from

their point of view. It was fun to get up by

lamp-light, when the stars were still shining in

the sky; fun to find that rules were relaxed, and

for once they might chatter and talk as they

pleased; fun to run unreproved along the passages,

sing on the stairs, and twirl one another

round in an impromptu dance in the hall.

The particular occupants of the Blue Bedroom

had been astir even before the big bell clanged

for rising, so they stole a march over rival dormitories,

performed their toilets, packed their hand-bags,

strapped their wraps, and proceeded downstairs

to the dining-hall, where cups and plates

were just being laid upon the breakfast-table. It

was quite superfluous energy on the part of

Lilias, Dulcie, Gowan, and Bertha, for as a matter

of fact not one of them was on the list of

earliest departures, but the excitement of the general

exodus had awakened them as absolutely as

the advent of Santa Claus on Christmas mornings.

They stood round the newly-lighted fire,

warming their hands, chatting, and hailing fresh

arrivals who hurried into the hall.

"You going by the 6.30, Edith? You lucker!

My train doesn't start till ten! I begged and

implored Miss Walters to let me leave by the[3]

early one, and wait at the junction, but she would

not hear of it, so I've got to stop here kicking my

heels, and watch you others whisked away. Isn't

it a grisly shame?"

Gowan's round rosy face was drawn into a decided

pout, and her blue eyes were full of self-pity.

She had to be sorry for her own grievance,

because nobody else had either time or much inclination

to sympathize; they were all far too

much excited about their own concerns.

"Well, you'll get off sometime, I suppose,"

returned Edith airily. "There are twelve of us,

all going together as far as Colminster. We

mean to cram into one carriage if we can. Don't

suppose the train will be full, as it's so early. I

thought you were coming with us, Bertha, but

Miss Hardy says you're not!"

"Dad changed his mind at the last minute, and

promised to send the car to fetch me. It's only

forty miles by road, you know, though it takes

hours by the train. He seemed to think I should

lose either myself or my luggage at Sheasby Junction,

and it is a horrid place to change. You

never can get hold of a porter, and you don't

know which platform you'll start from."

"How are you going home, Lilias?" asked

Noreen, who with several other girls had joined

the group at the fire.

Lilias, squatting on the fender, stretching two[4]

cold hands towards the blazing sticks, looked up

brightly.

"We're riding! Astley and Elton are to fetch

Rajah and Peri over for us. Grandfather said

they needed exercise. I don't suppose he'd have

thought of it, only Dulcie wrote to Cousin Clare

and begged her to ask him. Won't it be just

splendiferous? We haven't had a ride the whole

term, and I'm pining to see Rajah!"

"Grandfather had promised to let us ride to

school in September," put in Dulcie, "but Everard

and a friend of his commandeered the horses

and went to Rasebury, so we couldn't have them,

and we were so disappointed. I do hope nothing

will happen to stop them this time! Everard

was to arrive home yesterday, so he'll be before

us. I shan't ever be friends with him again if he

plays us such a mean trick!"

"It's 'coach—carriage—wheelbarrow—truck,'

it seems to me, the way we're all trotting

home!" laughed Edith. "If I could have my

choice, I'd sprint on a scooter!"

"Next term we'll travel by private aeroplane,

specially chartered!" scoffed Noreen.

"I don't mind how I go, so long as I get off

somehow!" chirped Truie. "Thank goodness,

here come the urns at last! I began to think

breakfast would never be ready. We want to

have time to eat something before we start."

[5]Miss Walters' excellent arrangements had left

ample time for the healthy young appetites to be

satisfied before the taxis arrived at the door to

convey the first contingent of pupils to the station.

Sixteen girls, under the escort of a mistress,

took their departure in the highest of spirits,

packed as tightly as sardines, but managing to

wave good-bys. Their boxes had been dispatched

the previous day, their hand-bags had

gone on by cart before breakfast and would be

waiting for them at the station, where Jones, that

most useful factotum, would, by special arrangement

with the station-master, be taking their

tickets before the ordinary opening of the booking-office.

Though the departure of sixteen girls made

somewhat of a clearance at Chilcombe Hall, Miss

Walters' labors were not yet over. There was

a train at eight and a train at ten, and the young

people who had to wait for these found it difficult

to know how to employ the interval until it

was their turn to enter the taxis. By nine o'clock

Lilias and Dulcie, ready in their riding habits,

were looking eagerly out of the dining-hall window

along the drive which led to the gate.

"I know Elton would be early," said Dulcie.

"It's always Astley who stops and fusses. It

was the same when Everard went cub-hunting.

You don't think there's a hitch, do you?" (uneasily).[6]

"Shall we get a horrid yellow envelope

and a message to say 'Come by train'? It would

be too bad, and yet, it's as likely as not!"

Dulcie's fears, which in the course of twenty

minutes' waiting and watching had almost conjured

up the telegraph boy with his scarlet bicycle

and brown leather wallet, were suddenly dispelled,

however, by a brisk sound of trotting, and

a moment later appeared the welcome sight of

her grandfather's two grooms riding up to the

house, each leading a spare horse by the rein.

Those schoolfellows who had not yet departed

to the station came to the door to witness the

interesting start. A sleek, well-groomed horse is

always a beautiful object, and the girls decided

unanimously that Lilias and Dulcie were lucky to

be carried home in so delightful a fashion. They

watched them admiringly as they mounted.

Edith stroked Rajah's smooth neck as she said

good-by to her friends.

"Riding beats motoring in my opinion," she

vouchsafed, "though of course you can go farther

in a car. Perhaps I shall pass you on the

road."

"No, you won't, for we're taking a short cut

across country. We always choose by-lanes if

we can. Write and tell me if you get a motor-scooter.

They sound fearfully thrillsome.

Good-by, see you again in January!"

[7]"Good-by! and a merry Christmas to everybody!"

added Dulcie, turning on her saddle to

wave a parting salute to those who were left behind

on the doorstep.

The two girls walked their horses down the

drive, but once out on the level road they trotted

on briskly, with the grooms riding behind. They

formed quite a little cavalcade as they turned

from the hard motor track down the grassy lane

where a dilapidated sign-post pointed to Ringfield

and Cheverley. It was a distance of seven good

country miles from Chilcombe Hall to Cheverley

Chase, and, as the events of this story center

largely round Lilias and Dulcie, there will be

ample time to describe them while they are wending

their way through the damp of the misty

December morning, up from the low-lying river

level to the hill country that stretched beyond.

Lilias was just sixteen, and very pretty, with

gray eyes, fair hair, a straight nose, and two

bewitching dimples when she smiled. These

dimples were rather misleading, for they gave

strangers the impression that Lilias was humorous,

which was entirely a mistake: it was Dulcie

who was the humorist in reality, Dulcie whose

long lashes dropped over her shy eyes, and who

never could say a word for herself in public,

though in the society of intimate friends she could

be amusing enough. Dulcie, at fourteen, seemed[8]

years younger than Lilias; she did not wish to

grow up too soon, and thankfully tipped all responsibilities

on to her elder sister. Cousin

Clare always said there were undiscovered depths

in Dulcie's character, but they were slow in development,

and at present she was a childish little

person with a pink baby face, an affection for

fairy tales, and even a sneaking weakness for her

discarded dolls. Life, that to Lilias seemed a

serious business, was a joyous venture to Dulcie;

she had a happy knack of shaking off the unpleasant

things, and throwing the utmost possible

power of enjoyment into the nice ones. If innocent

happiness is the birthright of childhood,

she clung to it steadfastly, and had not yet

exchanged it for the red pottage of worldly

wisdom.

Ever since Father and Mother, in the great

disaster of the wreck of the Titanic, had gone

down together into the gray waters of the Atlantic,

the Ingleton children had lived with their

grandfather, Mr. Leslie Ingleton, at Cheverley

Chase. There were six of them, Everard, Lilias,

Dulcie, Roland, Bevis, and Clifford, and as time

passed on, and the memory of that tragedy in mid-ocean

grew faint, the Chase seemed as entirely

their home as if they had been born there. In

Everard's opinion, at any rate, it belonged to

them, as it had always belonged to the prospective[9]

heirs of the Ingleton family. And that

family could trace back through many centuries to

days of civil wars and service for king and country,

to crusades and deeds of chivalry, and even

to far-away ancestors who gave counsel at Saxon

Witenagemots. Norman keep had succeeded

wooden manor, and that in its turn had given

place to a Tudor dwelling, and both had finally

merged into a long Georgian mansion, with

straight rows of windows and a classic porch, not

so picturesque as the older buildings, but very

convenient and comfortable from a modern point

of view. The lovely gardens, with their clipped

yew hedges, were one of the sights of the neighborhood,

and it was a family satisfaction that the

view from the terrace over park, wood, and

stream showed not a single acre of land that was

not their own.

Mr. Leslie Ingleton, a fine type of the old-fashioned,

kindly, but autocratic English squire,

belonged to a bygone generation, and found it

difficult to move with the march of the times.

Because he had spent his seventy-four years of

life on the soil of Cheverley, the people tolerated

in "the ould squire" many things that they would

not have passed over in a younger man or a

stranger. They shrugged their shoulders and

gave way to his well-meant tyranny, for man and

boy, everybody on the estate had experienced his[10]

kindness and realized his good intentions towards

his tenants.

"If he does fly off at a tangent, ten to one Miss

Clare'll be down the next day and set all straight

again," was the general verdict on his frequent

outbursts.

Cheverley Chase would have been quite incomplete

without Cousin Clare. She was a second

cousin of the Ingletons, who had come to tend

Grandmother in her last illness, and after her

death had remained to take charge of the household

and the newly-arrived family of grandchildren.

She was one of those calm, quiet, big-souled

women who in the early centuries would

have been a saint, and in mediæval times the abbess

of a nunnery, but happening to be born in

the nineteenth century, her mental outlook had

a modern bias, and both her philanthropy and her

religious instincts had developed along the latest

lines of thought. She had schemes of her own

for work in the world, but at present she was doing

the task that was nearest in helping to bring

up the motherless children who had been placed

temporarily in her care. To manage this rather

turbulent crew, soothe the irascible old Squire,

and keep the general household in unity was a

task that required unusual powers of tact, and a

capacity for administration and organization that

was worthy of a wider sphere. She might be[11]

described as the axle of the family wheel, for she

was the unobtrusive center around which everything

unconsciously revolved.

But by this time Lilias and Dulcie will have

ridden up hill and down dale, and will be turning

Rajah and Peri in at the great wrought-iron gates

of Cheverley Chase, and trotting through the

park, and up the laurel-bordered carriage drive to

the house. There was quite a big welcome for

them when they arrived. Everard had returned

the day before from Harrow, Roland was back

from his preparatory school, and the two little

ones, Bevis and Clifford, had just said good-by

for three weeks to their nursery governess, and

in consequence were in the wildest of holiday

spirits. There was a general family pilgrimage

round the premises to look at all the most cherished

treasures, the horses, the pigeons, the pet

rabbits, the new puppies, the garden, and the

woods beyond the park; there were talks with the

grooms and the keepers, and plans for cutting

evergreens and decorating both the house and

the village church in orthodox Christmas fashion.

"It's lovely to be at home again," sighed Lilias

with satisfaction, as the three elder ones sauntered

back through the winding paths of the terraced

vegetable garden.

"And such a home, too!" exulted Dulcie.

"Rather!" agreed Everard. "That was exactly[12]

what was in my mind. The first thing I

thought when I looked out of the window this

morning was: 'What a ripping place it is, and

some day it will be all mine.'"

"Yours, Everard?"

"Why, of course. Who's else should it be?

The Chase has always gone strictly in the male

line, and I'm the oldest grandson, so naturally

I'm the heir. It goes without saying!"

Dulcie's pink face was looking puzzled.

"Do you mean to say if Grandfather were to

die, that everything would be yours?" she asked.

"Would you be the Squire?"

"I believe I'm called 'the young squire' already,"

replied Everard airily.

"But what about the rest of us?" objected

Dulcie.

"Oh, I'd look after you, of course! The heir

always does something for the younger ones.

You needn't be afraid on that score!"

Everard's tone was magnanimous and patronizing

in the extreme. He was gazing at the house

with an air of evident proprietorship. Dulcie,

who had never considered the question before,

revolved it carefully in her youthful brain for a

moment or two; then she ventured a comment.

"Wouldn't it be fairer to divide it?"

"Nonsense, Dulcie!" put in Lilias. "You

don't understand. Properties like this are never[13]

divided. They always go, just as they are, to

the eldest son. You couldn't chop them up into

pieces, or there'd be no estate left."

"Couldn't one have the house and the other

the wood, and another the park?"

"Much good the house would do anybody

without the estate to keep it up!" grunted Everard.

"Dulcie, you're an utter baby. I don't

believe you ever see farther than the end of your

silly little nose. You may be glad you've got a

brother to take care of you."

"But haven't I as much right here as you?"

persisted Dulcie obstinately.

"No, you haven't; the heir always has the best

right to everything. Cheer up! When the

place is mine, I mean to have a ripping time here!

I'll make things hum, I can tell you—ask my

friends down, and you girls shall help to entertain.

I've planned it all out. I suppose I shall

have to go to Cambridge first, but I'll enjoy myself

there too—you bet! On the whole I think

I was born under a lucky star! Hallo! there goes

Astley; I want to speak to him."

Everard whistled to the groom, and ran down

the garden, leaving his sisters to return to the

house. At seventeen he was a fair, handsome,

dashing sort of boy, of a type more common

thirty years ago than at present. He held closely

to the old-fashioned ideas of privileges of birth,[14]

and, according to modern notions, had contracted

some false ideals of life. He had lounged

through school without attempting to work, and

was depending for all his future upon what should

be left him by the industry of others. All the

same, in spite of his attitude of "top dog" in the

family, he was attractive, and inclined to be generous.

Like most boys of seventeen, he had

reached the "swollen head" stage, and imagined

himself of vastly greater importance than he really

was. The sobriquet of "the young squire"

pleased his fancy, and he meant to live up to what

he considered were the traditions of so distinguished

a title.

chapter ii

A Stolen Joy-ride

Christmas passed over at Cheverley Chase in[15]

good old-fashioned orthodox mode. The young

Ingletons, with plenty of evergreens to work

upon, performed prodigies in the way of decorations

at church and home. They distributed

presents at a Christmas-tree for the children of

tenants, and turned up in a body to occupy the

front seats at the annual New Year's concert in

the village. When the usual festivities were finished,

however, time hung a little heavy on their

hands, and one particular morning found them

lounging about the breakfast-room in the especially

aggravating situation of not quite knowing

what to do with themselves.

"It's too bad we can't have the horses to-day!"

groused Dulcie. "I'd set my heart on a

ride, and I can't get on with my fancy work till I

can go to Balderton for some more silks."

"And I want some wool," proclaimed Lilias,

stopping from a rather unnecessary onslaught of

poking at the fire. "There's never anything fit[16]

to buy at this wretched little shop in the village!"

"Except bacon and kippers!" grinned Roland.

"I can't knit with kippers!"

"Fact is, we're all bored stiff!" drawled

Everard from the sofa, flinging away the book he

was reading, and stretching his arms in the luxury

of a long-drawn yawn. "What should you say

to a turn in the car? Wouldn't it be rather

sport, don't you think?"

"If Grandfather would spare Milner to take

us!" said Lilias doubtfully.

"We don't want Milner. I'll drive you! I

can manage a car as well as he can, any day.

Don't get excited, you kids! No, Bevis, I shall

certainly not allow you to try to drive! There's

only going to be one man at that job, and that's

myself!"

"Shall we go and ask Grandfather?" suggested

Dulcie.

"Right you are! No, not the whole of us,"

(as there was a general family move). "Three's

enough!"

So a deputation, consisting of Everard, Lilias,

and Dulcie, promptly presented themselves at the

study door and tapped for admission. As there

was no reply to a second rap, they opened the

door and walked into the room. Grandfather

was rather deaf, and sometimes, when he had

ignored a summons, he would say: "Well, why[17]

didn't you come in?" He was generally to be

found writing letters at this hour in the morning,

but to-day the revolving chair was empty. He

had apparently begun his usual correspondence,

for his desk was littered with papers. Leaning

up against the ink-pot there was a photograph.

The young people, who had walked across the

room towards the window, could not fail to notice

it, for it was tilted in such a prominent place

that it at once attracted their attention. It represented

a very pretty dark-eyed young lady, holding

a baby on her lap, with a slight background

of Greek columns. The decidedly foreign look

about it was justified by the photographer's name

in the corner: "Carlo Salviati, Palermo."

Over the top was written in ink, in a man's handwriting:

"My wife and Leslie, from Tristram."

"Who is it?" asked Everard, gazing at the

portrait with curiosity. "She's rather decent

looking. Never seen her here, though, that I can

remember!"

"It's a ducky little baby! But who is Tristram?"

said Dulcie.

"We had an Uncle Tristram once," answered

Lilias doubtfully.

"Why, but he died years and years ago, when

we were all kids!" returned Everard.

"I know. He was the only Tristram in the[18]

family, though. I can't imagine who these two

can be. Leslie, too! Why, that's Grandfather's

name! Was the baby christened after him?"

"We'll ask Cousin Clare sometime," said Dulcie,

so interested that she could scarcely tear

herself away. "I really want to know most fearfully

who they are."

"Oh, don't bother about photos at present!

Let's find Grandfather!" urged Everard.

"Perhaps he's gone down to the stables, or he

may be in the gun-room."

On further inquiry, however, they ascertained

that a telegram had arrived for Mr. Ingleton, on

the receipt of which he had consulted Miss Clare,

had ordered the smaller car, and they had both

been driven away by Milner, the chauffeur, and

were not expected back until seven or eight o'clock

in the evening. This was news indeed. For a

whole day the heads of the establishment would

be absent, and the younger generation had the

place to themselves. For the next eight hours

they could do practically as they pleased.

Everard stood for a moment thinking. He

did not reveal quite all that passed through his

mind, but the first instalment was sufficient for the

family.

"We'll get out the touring car, take some lunch

with us, and have a joy-ride."

Five delighted faces smiled their appreciation.

[19]"Oh, Everard! Dare we?" Dulcie's objection

was consciously faint.

"Why not? When Grandfather's away, I

consider I've a right to take his place and use the

car if I want. I'm master here in his absence!

I'll make it all right with him; don't you girls

alarm yourselves! Tear off and put on your

coats, and tell Atkins to pack us a basket of lunch,

and to put some coffee in the thermos flasks."

With Everard willing to assume the full responsibility

the girls could not resist such a tempting

offer, while the younger boys were, of course,

only too ready to follow where their elders led.

Elton, the groom, made some slight demur when

Everard went down to the motor-house and began

to get out the big touring-car, but the boy

behaved with such assurance that he concluded

he must be acting with his grandfather's permission.

Moreover, Elton was in charge of the

horses, and not the cars, and Milner, the chauffeur,

who might reasonably have raised objections,

was away driving his master.

The cook, who perhaps considered it was no

business of hers to offer remonstrances, and that

the house would be quieter without the young

folks, hastily packed a picnic hamper and filled

the thermos flasks. A rejoicing crew carried

them outside and stowed them in the car.

It seemed a delightful adventure to go off in[20]

this way entirely on their own. There was some

slight wrangling over seats, but Everard settled

it in his lofty fashion.

"You'll sit where I tell you. I'll have Lilias

in front, and the rest of you may pack in behind.

If you don't like it, you can stop at home. No,

I'm not going to have you kids interfering here,

so you needn't think it."

Everard had been taught by the chauffeur to

drive, and could manage a car quite tolerably

well. He possessed any amount of confidence,

which is a good or bad quality according to circumstances.

He ran the large touring "Daimler"

successfully through the park, and turned

her out at the great iron gateway on to the highroad.

Everybody was in the keenest spirits. It

was a lovely day, wonderfully mild for January,

and the sunshine was so pleasant that they hardly

needed the thick fur rugs. There seemed a hint

of spring in the air; already hazel catkins hung

here and there in the hedgerows, thrushes and

robins were singing cheerily, and wayside cottages

were covered with the blossom of the yellow jessamine.

It was a joy to spin along the good

smooth highroad in the luxurious car. Everard

was a quick driver, and kept a pace which sometimes

exceeded the speed limit. Fortunately his

brothers and sisters were not nervous, or they

might have held their breath as he dashed round[21]

corners without sounding his horn, pelted down

hills, and on several occasions narrowly avoided

colliding with farm carts. A reckless boy of

seventeen, without much previous experience,

does not make the most careful of motorists. As

a matter of fact it was the first time Master

Everard had driven without the chauffeur at his

elbow, and, though he got on very well, his performance

was not unattended with risks.

Towards one o'clock the crew at the back began

to clamor for lunch, and to suggest a halt

when some suitable spot should be reached. The

difficulty was to find a place, for they were driving

so fast that by the time the younger boys had

called out the possibilities of some wood or small

quarry, the car had flown past, and, sooner than

turn back, Everard would say: "Oh, we'll stop

somewhere else!"

By unanimous urging, however, he was at last

persuaded to halt at a picturesque little bridge in

a sheltered hollow, where they had the benefit of

the sunshine and escaped the wind. A small

brook wandered below between green banks

where autumn brambles still showed brown leaves,

and actually a shriveled blackberry or two remained.

There was a patch of grass by the roadside,

and here Everard put the car, to be out of

reach of passing traffic, while its occupants spread

the rugs on the low wall of the bridge, and began[22]

to unpack their picnic baskets. Cook had certainly

done her best for them: there were ham

sandwiches and pieces of cold pie, and jam turnovers,

and slices of cake, and some apples and

oranges, and plenty of hot coffee in the thermos

flasks.

"It's ever so much nicer to have one's meals

out-of-doors, even in January!" declared Bevis,

munching a damson tartlet, and dropping stones

into the brook below. "I believe it's warm

enough to wade. That water doesn't look cold,

somehow!"

"No, you don't!" said Lilias briskly. "You

needn't think, just because Miss Mason isn't here,

you can do all the mad things you like. It's no

use beginning to unlace your boots, for I shan't

let you wade, or Clifford either! The idea! In

January!"

"Why not?" sulked Bevis. "I didn't ask

you, Lilias. Everard won't say no!"

"You can please yourselves," answered his

eldest brother, "but I'm going to take the car on

now. If you stay and wade, you'll have to walk

home, that's all! I certainly shan't came back

for you."

At so awful a threat the youngsters, who had

really meant business where the water was concerned,

hurriedly relaced their boots, and ran to

take their places in the car; the girls finished packing[23]

the remains of the picnic in the basket, and

followed, and soon the engine was started again,

and they were once more flying along the road.

Everard had brought out the family for a joy-ride

without any very particular idea of where

they were going, though he was steering generally

in the direction of the Cleland Hills. To his

mind the chief fun of the expedition lay in simply

taking any road that looked interesting, without

regard to sign-posts. The others trusted implicitly

to his powers of path-finding, and had really

not the slightest idea in what part of the country

they were traveling. After quite a long time,

however, it occurred to Lilias to ask where they

were, and how long it would take them to get

home again.

"We've come such a roundabout route, I

scarcely know," replied Everard. "Those are

the Cleland Hills in front of us, though, and if

we bowl straight ahead, and go over them, we

shall get to Clacton Bridge; then we can get the

straight highroad back to Cheverley."

"We shan't be home before it's dark,

though?"

"Well, no! But the head lights are working

all right—I tried them before we started."

"It will be fun to drive in the dark!" chuckled

the boys behind.

"I hope we shall be back before Grandfather[24]

and Cousin Clare, though," said Dulcie a little

uneasily.

The road over the Cleland Hills was much

wilder than they expected, and it was very stony

and bad. Up and up they went till walls, hedges

and farms had disappeared, and only the lonely

moor lay on either side of the rough track. It

was a place where no motorist in his senses would

have ventured to take a car, the extreme roughness

of the road made steering difficult, and the

strain on the tires was enormous. Instead of

driving cautiously, Everard plunged along with

all the hardihood of youth, bumping anyhow over

ruts and stones. They were just beyond the

brow of the hill when a loud bang, followed by a

grinding sensation, announced the bad news that

one of their tires had burst.

"What beastly bad luck!" lamented Everard,

getting out to inspect the injured cover. "It

might have had the decency to keep up till we had

reached civilization! Well, there's nothing for

it but to put on the spare tire. I've helped Milner

to do it before, so I can manage. It's a

bother we left the spare wheel at home. I shall

want some of you to help me, though."

Everard had indeed rendered some assistance

to the chauffeur on various occasions, but it was

quite another matter to perform the troublesome

operation of changing the tire with only two girls[25]

and three young brothers to lend a hand. In

their inexperienced enthusiasm, they did all the

wrong things, very nearly nipped the tube, mislaid

the tools, and pulled where they should have

pushed. It was only after nearly an hour's work

that Everard at last managed to get the business

finished. The family, warm and excited, packed

once more into the car.

"Well, I hope we shall have no more troubles

now!" exclaimed Lilias, who was growing tired

and longing for home and tea. "What's the

matter, Everard?"

"Matter! Why, she won't start, that's all!"

Here was a predicament! Whether the bumping

up the rough road had thrown some delicate

piece of mechanism out of gear, or the waiting in

the cold had cooled the engine, it was impossible

to say, but nothing that Everard could do would

induce the car to start. He examined everything

which his rather limited knowledge of motorology

suggested might be the cause of the stoppage, but

with no result. After half an hour's tinkering,

he was obliged ruefully to acknowledge himself

utterly baffled.

They were indeed in an extremely awkward

situation, stranded on a wild moor, probably sixty

miles from home, and with the short winter's day

closing rapidly in.

[26]"What are we to do?" gasped Lilias, half-crying.

"We can't stay here all night!"

"Finish our prog and sleep in the car," suggested

Roland.

"No, no! We should be frozen before morning."

"I think we'd better walk on while it's light

enough to see," said Everard. "We shall probably

strike a highroad soon, and we'll stop some

motorist, ask for a lift to the nearest town, and

stay all night at a hotel."

"But what about the car?"

"We must just leave her to her fate. There's

nothing else for it. I don't suppose anybody

will touch her up here. It can't be helped, any

way."

"Let's finish our prog before we set off!" persisted

Roland, opening the picnic basket.

The family was hungry again, so they readily

set to work to dispose of the remains of their

lunch. It might be a long time before they were

within reach of their next meal, and they blessed

Cook for having packed a plentiful supply.

Everard would not let them linger for more than

a few minutes.

"Hurry up, you kids!" he urged. "We

don't know how far we may have to go, and it

[27]will be getting dark soon. Thank goodness we

shall be walking down hill, at any rate."

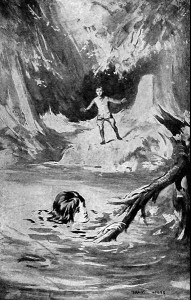

"what are we to do!" gasped lilias

After whisking along in the car, "Shanks's

pony" seemed a very slow mode of progress;

their breakdown had happened in an out-of-the-way

spot, and it was more than an hour before

they reached a highroad. It was almost dark by

that time, and matters seemed so desperate that

Everard determined to hail the very first passing

motorist who seemed to be able to help them.

Fate brought along no handsome tourist car, but

a rattling motor-lorry, the driver of which stopped

in answer to their united shouts, and, after hearing

of the difficulty they were in, consented to give

them a lift to the town, five miles away, for which

he was bound. Fortunately the lorry was empty,

so the family thankfully climbed in, and squatted

on the floor, while Everard sat in front with the

driver.

It was not a very aristocratic mode of conveyance

for the heir of Cheverley Chase, but Everard

was in no mood to pick and choose just then, and

would have accepted a seat in a coal truck if necessary.

As for the younger ones, they enjoyed

the fun of it. It was a very bumpy performance

to sit on the floor of the jolting wagon, but at any

rate infinitely preferable to walking.

Arrived in Bilstone, their cicerone drove them

to a Commercial Hotel with whose landlady he[28]

had some acquaintance, and that good dame, after

eyeing the party curiously, consented to make up

beds for them for the night.

"I've no private sitting-room to put you in,

and I can't show these young ladies into the commercial

room," she objected; "but I'll have a fire

lighted in one of the bedrooms, and you can all

have some tea up there. Will that suit you?"

Lilias and Dulcie, catching a glimpse through

an open door of the company smoking in the commercial

room, agreed thankfully, glad to find

some safe haven to which they could beat a retreat.

"I wonder what Cousin Clare would say?"

they asked each other.

It was indeed an urgent matter to send some

news of their whereabouts to Cheverley Chase,

where their absence must be causing much alarm.

While the landlady, therefore, ordered the tea,

Everard went out to the public telephone, asked

for a trunk call, and rang up No. 169 Balderton.

He could hear relief in the voice of old Winder,

who answered the telephone. Everard was not

anxious to enter into too many explanations, so

he simply said that they had had a breakdown,

told the name of the town and the hotel where

they were staying, and suggested that Milner

should come over next morning to the rescue. On

hearing his Grandfather's voice, he promptly rang[29]

off. To-morrow would be quite time enough, so

he felt, for giving the history of their adventure.

The unpleasant interview might just as well be

deferred, and he had no wish to listen to explosions

of anger over the telephone.

Tea, tinned salmon, plum and apple jam, and

very indifferent bedrooms were the best that the

Commercial Hotel had to offer, but it was infinitely

better than being benighted on the moor.

In spite of lack of all toilet necessaries, the Ingletons

slept peacefully, worn out with their long day

in the fresh air. Milner, the chauffeur, must have

made an early start, for he arrived at eleven

o'clock next morning in the small car, armed with

his master's instructions. He paid the hotel bill,

chartered a taxi, in which he dispatched Lilias,

Dulcie, Roland, Bevis and Clifford, straight for

home, then, engaging a mechanic from a garage,

and taking Everard as guide, he started up the

hill in the pouring rain to find the abandoned car.

It needed several hours' attention before it could

be induced to start, and it was not until evening

that he was able to place it safely back in the

motor-house at Cheverley Chase.

Everard had expected his peppery grandfather

to be angry, but he was quite unprepared for the

intensity of the storm which burst over his head

on his return.

"Your insolence goes beyond all bounds!"[30]

thundered Mr. Ingleton. "To borrow my car

without leave! And to take your sisters without

a chaperon to a fifth-rate public-house! You deserve

horsewhipping for it! You think yourself

the young Squire, do you? And imagine you can

do just what you like here? While I'm above

ground I'll have you to know I'm master, and nobody

else in this place!"

"I can't see it was anything so out of the way

to take the kids a run in the car, and I never

meant to keep the girls out all night," replied

Everard defiantly. He had a temper as well as

his grandfather, and the pair had often been at

loggerheads before.

"Indeed! There are ways of making people

see! You can just go a little too far sometimes!"

declared the old gentleman sarcastically. "I've

given orders that you don't take either car out

again unless Milner is with you. So you understand?"

"I suppose I do," grunted Everard, turning

sulkily away.

It was only a few days after this that Everard,

Lilias, and Dulcie, returning home across the park

from a walk in the woods, met Mr. Bowden, the

family solicitor, who was riding down the drive

from the Chase. He stopped his motor-bicycle

and got off to speak to them. They knew him

well, for he often came to the house to conduct[31]

their grandfather's business, and he was indeed

quite a favorite with them all. He looked at

Everard keenly when the first greetings were over.

"Been getting yourself into considerable hot

water just lately, haven't you?" he remarked.

Everard colored and frowned, then burst forth.

"Grandfather's quite too ridiculous! Why

shouldn't I take out the car if I want to? I can

drive as well as Milner! He behaved as if I

were a kid! It's more than a fellow can stand

sometimes! He likes to keep everything tight

in his own hands; at his age it's time he began to

stand aside a little and let me look after things!

I shall have to take charge of the whole property

some day, I suppose!"

Mr. Bowden was gazing at Everard with the

noncommittal air often assumed by lawyers.

"I wouldn't make too sure about that," he said

slowly. "I suppose you know your Uncle Tristram

left a child? No! Well, he did, at any

rate. I must hurry on now. I've an appointment

to keep at my office. A happy New Year

to you all. Good-by!"

And, starting his engine, he was off before they

had time to reply.

"What does he mean?" asked Lilias, watching

the retreating bicycle. "Uncle Tristram has been

dead for thirteen years! We never seem to have

heard anything about him!"

[32]"What was that photo we saw on the study

table?" queried Dulcie. "Don't you remember—the

lady and the baby, and it had written on it:

'My wife and Leslie, from Tristram.'"

"I suppose it was Uncle Tristram's wife and

child," replied Everard thoughtfully. "He

must have called the kid 'Leslie' after Grandfather.

They ought to have christened me

'Leslie.' I can't think why they didn't."

"Have we a cousin Leslie, then, whom we

don't know?"

"I suppose we must have, somewhere!"

"How fearfully thrilling!"

"Um! I don't know that it's thrilling at all.

It's the first I've heard of it until to-day. I wish

our father had been the eldest son, instead of

Uncle Tristram!"

"Why? What does it matter?"

"It may matter more than you think. You're

a silly little goose, Dulcie, and, as I often tell you,

you never see farther than the end of your own

nose. Surely, after all these years, though,

Grandfather must——"

"Must what?" asked Lilias curiously.

"Never you mind! Girls can't know everything!"

snapped Everard, walking on in front of

his sisters with a look of unwonted worry upon

his usually careless and handsome young face.

chapter iii

A Valentine Party

Chilcombe Hall, where Lilias and Dulcie had[33]

been boarders for the last two years, was an exceedingly

nice school. It stood on a hill-side well

raised above the river, and behind it there was

a little wood where bulbs had been naturalized,

and where, in their season, you might find clumps

of pure white snowdrops, sheets of glorious daffodils,

and later on lovely masses of the lily of the

valley. In the garden all kinds of sweet things

seemed to be blooming the whole year round.

Golden aconite buds opened with the January

term, and in a wild patch above the rockery the

delicious heliotrope-scented Petasites fragrans

blossomed to tempt the bees which an hour's sunshine

would bring forth from the hives, scarlet

Pyrus japanica was trained along the wall under

the front windows, and early flowering cherry and

almond blossoms made delicate pink patches of

color long before leaves were showing on the

trees.

Beautiful surroundings in a school can be quite[34]

as important a part of our education as the textbooks

through which we toil. We are made up

of body, mind, and spirit, and the developing soul

needs satisfying as much as the physical or mental

part of us. Long years afterwards, though we

utterly forget the lessons we may have learnt as

children, we can still vividly recall the effect of

the afternoon sun streaming through the fuchsia

bush outside the open French window where we

sat conning those unremembered tasks. The

lovely things of nature, assimilated half unconsciously

when we are young, equip us with a

purity of heart and a refinement of taste that

should safeguard us later, and keep our thoughts

at a lofty level.

The "beauty cult" was a decided feature of

Chilcombe Hall. Miss Walters was extremely

artistic; she painted well in water-colors and had

exquisite taste. Many of the charming decorations

in the house had been done by herself; she

had designed and stencilled the frieze of drooping

clusters of wistaria that decorated the dining-hall

wall; the framed landscapes in the drawing-room

were her own work, and she herself always

superintended the arrangement of the bowls of

flowers that gave such brightness to the schoolrooms.

Her twenty pupils had on the whole a decidedly

pleasant time. There were just enough of them[35]

to develop the community spirit, but not too many

to obliterate the individual, or, as Ida Spenser

put it: "You can get up a play, or a dance, or

any other sort of fun, and yet we all know each

other like a kind of big family."

"Divided up into small families according to

bedrooms!" added Hester Wilson.

The bedrooms at Chilcombe Hall were rather

a speciality. They were large, and were furnished

partly as studies, and girls had their own

bookcases, knick-knacks, and pretty things there.

As the house was provided with central heating,

they were warmed, and a certain amount of preparation

was done in them each afternoon. Miss

Walters' artistic faculty had decorated them in

schemes of various colors, so that they were

known respectively as The Rose, The Gold, The

Green, The Brown, and The Blue Bedrooms.

Lilias and Dulcie Ingleton, Gowan Barbour, and

Bertha Chesters, who occupied the last-named,

considered it quite the choicest of all. They had

each made important contributions to its furniture,

had clubbed together to buy a Liberty table-cloth,

had provided vases in lovely shades of turquoise

blue, and had worked toilet-mats, nightdress

cases and other accessories to accord with

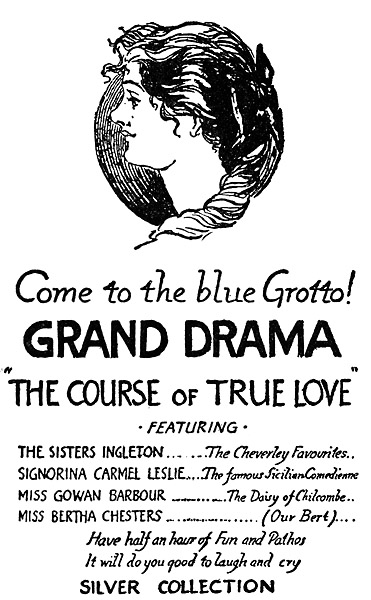

the prevailing tone. "The Blue Grotto," as they

named their dormitory, certainly had points over

rival bedrooms, for it looked down the garden[36]

towards the river, and had the best view of the

sunset. Moreover, it was at the very end of the

corridor, so that sudden outbursts of laughter did

not meet the ears of Miss Hardy quite so easily

as from the Rose or the Brown room.

The work of the spring term had been in full

swing for nearly a month, when Gowan Barbour,

looking at the calendar—hand-painted, with blue

cranesbill geraniums—suddenly discovered that

next morning would be the festival of St. Valentine.

"Could anything be better?" she exulted.

"We've won the record for tidiness three weeks

running, so we're entitled to a special indulgence.

I vote we ask to bring tea up here, and have a

Valentine party. Don't you think it would be

rather scrumptious? I've all sorts of ideas in

my head."

"Topping!" agreed Dulcie, pausing in the act

of tying her hair ribbon to consider the important

question, "specially if we could get Miss Walters

to let us send to Glazebrook for a few cakes. I

believe she would, if we wheedled!"

"What about visitors?" asked Lilias. "It

would be much more of a party if we had a few

of the others in."

"We don't want a crowd, or we might as well

be in the dining-hall," objected Bertha.

"Well, of course we shouldn't ask the whole[37]

school, naturally, but perhaps just Noreen and

Phillida!"

"We must get at the soft spot in Miss Walters'

heart," decided Gowan. "Pick a bunch of early

violets if you can find them, lay them on her study

table, talk about flowers and nature for a little

while, then ask if we may have a quiet little party

in our bedroom to-morrow afternoon, with cakes

at our own expense."

"Quiet?" queried Lilias.

"Well, of course you couldn't call it rowdy,

could you? We'll send you to do the asking.

Those dimples of yours generally get what you

want, and on the whole I think you're the pattern

one of us, and the most likely to be listened to."

Tea at Chilcombe Hall was a quite informal

meal. It partook, indeed more of the nature of

a canteen. The urns were what the girls called

"on tap" from four to four-thirty, and during

summer any one might take cup, saucer, and plate

into the garden, provided she duly brought them

back afterwards to the dining-hall. Special permission

for a bedroom feast was therefore not

very difficult to obtain, and Lilias returned from

her interview in the study with her dimples conspicuously

in evidence.

"Well?" asked the interested circle in the

Blue bedroom.

"Sweet as honey!" reported Lilias. "She[38]

said 'Certainly, my dear!' We may each ask

one friend, and we may spend two shillings

amongst us on cakes, if we give the money and

the list of what we want to Jones this afternoon,

because he's going into Glazebrook first thing to-morrow

morning."

"Only two shillings!" commented Gowan.

"It will go no way!" pouted Bertha.

"Well, I can't help it. Miss Walters said

'Two shillings' most emphatically."

"You might have stuck out for more! Those

iced cakes are always half a crown!"

"I didn't dare to stick out for anything. I

was so afraid she'd change her mind, and say

'There's good plain home-made cake with your

schoolroom tea, and you must be content with

that,' like she did to Nona and Muriel."

"We could get twelve twopenny cakes for

two shillings," calculated Dulcie; "but if there

are eight of us, that's only one and a half

apiece."

"Best get eight twopenny iced cakes, and eight

penny buns," suggested Bertha, taking pencil and

paper to write the important order.

"Right-o! Only be sure you put pink iced

cakes, they are so much the nicest."

"Whom shall we ask? It won't be much of a

beano on two shillings. Still, they'll be keen on

coming, I expect."

[39]Noreen, Phillida, Prissie, and Edith, the four

finally selected favorites, accepted the invitation

with alacrity. Bedroom tea-parties were indulgences

only given to winners of three weeks'

dormitory records, so the less fortunate occupants

of the Brown and Rose rooms were really profiting

by the tidiness of their hostesses. The Blue

Grotto was placed in apple-pie order on the afternoon

of the fourteenth of February. A white

hemstitched cloth and a bowl of snowdrops

adorned the center table, and the cakes were set out

on paper doilies. Both hostesses and guests were

in the dining-hall by four o'clock, awaiting the

appearance of the urns, and each bore her cup of

tea and a portion of bread and butter and scones

upstairs with her.

It was a jolly party round the square table, and

if the cakes were not too plentiful, they were at

least voted delicious. The girls carried down the

cups when they had finished, shook the table-cloth

out of the window, carefully collected crumbs

from the floor, so as to preserve their record for

neatness, then gathered round the table again for

an hour's fun before the bell should ring for

prep.

"It's a Valentine party, and I've got a ripping

idea," said Gowan. "We'll put our names on

pieces of paper, fold them up, shuffle them and

draw them; then each of us must write a valentine[40]

to the one we've drawn. We'll shuffle these,

and one of us must read them all out. Then we

must each guess who's written our valentines."

"Sounds rather brainy, doesn't it?" objected

Noreen. "I don't think I'm any hand at

poetry!"

"Oh! you can make up something if you try.

Valentines are generally doggerel."

"Need it be quite original?" asked Edith.

"Well, if you really can't compose anything,

we'll allow quotations."

"Cracker mottoes?" suggested Dulcie.

"Exactly. They're just about in the right

style."

"Are you all getting into a sentimental vein?"

giggled Bertha. "Remember 'Love' rhymes

with 'Dove,' and Cupid with—with—"

"Stupid," supplied Dulcie laconically.

"I'm not going to give my rhymes away beforehand,"

said Phillida. "Is that shuffling

business finished, Gowan? Then bags me first

draw."

Each girl, having been apportioned the name of

her valentine, set to work to compose a suitable

ode in her honor. There was much knitting of

brows and nibbling of pencils, and demands for a

few minutes longer, when Gowan called "Time!"

At last, however, the effusions were all finished,

folded, shuffled, and laid in a pile. Gowan, as[41]

the originator of the game, was unanimously

elected president. She drew one at a venture,

opened it, and read:

"TO PHILLIDA

"Fair maiden, who in ancient song

Was wont to flout her swain,

I prithee be not always coy,

But turn your face again.

My heart is true, and it will rue,

That ever you should doubt me,

So sweet, be kind, and change your mind,

And don't for ever flout me."

"Who wrote that?" asked Phillida, glancing

keenly round the circle. "Noreen, I believe

you're looking conscious! I always suspect people

who say they can't write."

"I! No, indeed!" declared Noreen.

"You may make guesses, but nobody's to confess

or deny authorship till the end," put in

Gowan hastily. "Remember, valentines are always

supposed to be anonymous. Now I'm going

to read another.

"TO LILIAS

"Cupid with his fatal dart

Shot me through and made me smart,

So I pray, before we part,

Kiss me once, and heal my heart!"

[42]"Short and sweet!" commented Edith.

"Very sweet—quite sugary, in fact," agreed

Lilias. "It's the sort of motto you get out of

a superior cracker with gelatine paper on the outside,

and trinkets inside. There ought to be a

ring with all that. I believe it's Prissie's, but

I'm not sure it isn't by Bertha."

"You mayn't have two guesses!" reminded

Gowan, reaching for another paper. "Hallo!

this actually to me! I feel quite shy!"

"Go on! You're not usually afflicted with

shyness," urged the others.

"TO GOWAN

"Wee modest, crimson-tipped flower,

Thou'st met me in an evil hour;

For I maun gang far frae thy bower,

And leave thee greeting 'mang the stour.

But lassie, thou art no thy lane,

This heart is also brak in twain,

And like to burst with grief and pain

To think I'll see thee ne'er again."

"H'm! He might have signed 'Robbie

Burns' at the end of it!" commented Gowan.

"Seems to take it for granted I'm doing half of

the grieving. No, thanks! I prefer to 'flout

them' like Phillida. He may go away with his

old broken heart if he likes. That's not my idea

of a valentine."

[43]"There were bad valentines as well as good

ones, weren't there?" twinkled Dulcie.

"Certainly; and if I set this down to you, perhaps

I'll not be far out. Who comes next? Oh! Bertha.

"TO BERTHA

"I have a little heart to let,

As nice as nice can be;

It's vacant just at present,

On a yearly tenancy.

It's quite completely furnished

With affection's choicest store,

Sweet nothings by the bushel,

And kisses by the score.

It sadly wants a tenant,

This little heart of mine,

So I beg that you will take it,

And be my Valentine!"

"Edith! Dulcie! Phillida!—Oh! I can't

guess!" laughed Bertha. "There's not the least

clue! Go on, Gowan! I'll plump for Phillida."

The next on the list was—

"TO NOREEN

"Cupid on his rosy wing

Flits to offer you a ring:

Take it, dear, and happy make

One who'd die for your sweet sake!"

[44]"That's the sugary type again, and suggests a

cracker!" decided Noreen. "You feel there

ought to be a big dish of trifle somewhere near."

"I wish there were!" chirped Edith. "You

haven't guessed yet!"

"Oh, well, I guess you!"

"I hope it's my turn next," said Prissie.

"No, it happens to be Dulcie," retorted

Gowan. "You'll probably be the last of all.

"TO DULCIE

"Oh, lady fair from Cheverley Chase,

The day when first I saw your face

Put me in such a fearful flutter

I could do naught but moan and mutter.

Whether I'm standing on my head,

Or if I'm on my heels instead,

I scarce can tell, for Cupid's arrows

Have made my brain like any sparrow's.

When you come near, my foolish heart

Goes pit-a-pat with throb and start,

And when I try my love to utter,

My fairest speech is but a stutter.

How to propose is all my task,

Whether to write or just to ask,

And ere I solve the problem knotty

I really fear I shall go dotty.

Oh, lady fair, in pity stop

And list while I the question pop.

'Tis here on paper; think it over,

And let me be your humble lover."

[45]"Quite the longest of them all!" smiled Dulcie

complacently.

"But not as poetical as mine!" contended

Noreen.

"Oh, go on!" said Edith. "I'm sure I'm

next!"

And so she was.

"TO EDITH

"Maiden of the swan-like neck,

I am at your call and beck;

If you will but wave a finger,

In your neighborhood I'll linger,

Praise your eyes, and cheeks of roses,

Bring you presents of sweet posies,

Sweetheart, if you will be mine,

Let me be your Valentine!"

"I haven't got a swan neck! It's no longer

than other people's, I'm sure!" protested Edith

indignantly, looking round the circle for the offender.

"Who wrote such stuff?"

"There, don't get excited, child!" soothed

Gowan. "'Edith of the Swan Neck' was a historical

character. Don't you remember? She

ought to have married King Harold, only she

didn't, somehow. It's meant as a compliment,

no doubt!"

"I believe you wrote it yourself!"

[46]"No, I didn't. At least I mustn't tell just yet.

I'm going to read the last one now.

"TO PRISSIE

"I am not sentimental, please,

I cannot write in rhyme,

I beg you'll all ecstatics leave

Until another time.

"But if I'm lacking in romance,

At least my heart is true,

And in its own prosaic way,

It only beats for you.

"'Mong damsels all I think you are

The nicest little Missie,

And beg to have for Valentine

That sweetest maid, Miss Prissie."

"Author! Author!" cried Prissie. "It's

Lilias, I do believe!"

"Guessing's been horribly wrong!" said

Gowan. "Only about one of you was right.

Shall I read the list?

"To Phillida by Dulcie.

To Lilias by Noreen.

To Gowan by myself.

To Bertha by Phillida.

To Noreen by Prissie.

To Dulcie by Bertha.

To Edith by Lilias.

To Prissie by Edith."

[47]"So you wrote your own, Gowan! What a

humbug you are! You quite put us off the

scent!"

"Well, I drew my own name, you see. I had

to write something! Bertha ought to have a

prize for guessing right, only we've nothing to

give her. Shall we play something else?"

"Prissie's brought a pack of cards, and she says

she'll tell our fortunes," proclaimed Edith.

"I learnt how in the holidays," confessed

Prissie. "A girl was staying with us who had a

book about it. We used to have ripping fun

every evening over it. Whose fortune shall I

tell first? Oh, don't all speak at once! Look

here, you'd better each cut, and the lowest shall

win."

Dulcie, who turned up an ace, was the lucky

one, and was therefore elected as the first to consult

the oracle. By Prissie's orders she shuffled

the cards, then handed them back to the sorceress,

who laid them out face upward in rows, and after

a few moments' meditation began her prophecies.

"You're fair, and therefore the Queen of Diamonds

is your representative card—all the

luck's behind you instead of facing you. I see a

disappointment and great changes. A dark

woman is coming into your life. She's connected

somehow with money, but there are hearts behind[48]

her. You'll take a journey by land, and

find trouble and perplexity."

"Haven't you anything nicer to tell me than

that?" pouted Dulcie. "Who's the dark

woman?"

"She seems to be a relation, by the way the

cards are placed."

"I haven't any dark relations. They're all as

fair as fair—the whole family."

"It's silly nonsense! I don't believe in it!"

declared Lilias emphatically.

"I dare say it is, but it's fun, all the same.

Do tell mine now, Prissie!" urged Noreen, gathering

up the cards and reshuffling them.

Before the fates could be further consulted,

however, the big bell clanged for preparation,

and the magician was obliged to pocket her cards,

hurry downstairs, get out her lesson books, and

write a piece of French translation, while the inquirers

into her mysteries also separated, some to

practise piano or violin, and some to study.

"A dark woman!" scoffed Dulcie, spilling the

ink in her scorn as she filled her fountain pen.

"Any gypsy would have told me a fortune like

that. I'll let you know when she comes along,

Prissie!"

"All serene! Bring her to school if you like!"

laughed Prissie. "You didn't let me finish, or I

might have gone on to something nicer. There[49]

were other things on the cards as well as those."

"What things?"

"Oh, I shan't tell you now, when you only

make fun of them! Sh! sh! Here's Miss Herbert!"

And Prissie, turning away from her comrade,

opened her French dictionary and plunged into the

difficulties of her page of translation from Racine.

chapter iv

Disinherited

Valentine's Day had brought early flowers, and[50]

the song of the thrush and glints of golden sunshine,

but the bright weather was too good to last,

and winter again stretched out an icy hand to

check the advance of spring. Green daffodil

buds peeped through a covering of snow, and the

yellow jessamine blossom fell sodden in the rain.

The playing-field was a quagmire, and the girls

had to depend upon walking for their daily exercise.

Their tramps were somewhat of an adventure,

for in places the swollen brooks were washing

over the tops of their bridges, and they would

be obliged to turn back, or go round by devious

ways. The river in the valley had overflowed

its banks and spread over the low-lying meadows

like a lake. Tops of gates and hedges appeared

above the flood, and sea-gulls, driven inland by

the gales, swam over the pastures. Flocks of

peewits, starlings, and red-wings collected on the

uplands, and an occasional heron might be seen

flitting majestically across the storm-flecked sky.

[51]As a rule the school sallied forth in waterproofs

and thick boots, regardless of drizzle or

slight snow, but on days of blizzard there was

Swedish drill or dancing in the big class-room, to

work off the superfluous energy accumulated during

hours of sitting still at lessons.

One afternoon, when driving sleet and showers

swept past the house, and an inclement sky hid

every hint of sunshine, the twenty girls, clad in

their gymnasium costumes, were hard at work doing

Indian club exercises. Dulcie, who stood in

the vicinity of the window, could watch the raindrops

splashing on the pane, and see the wet tree-tops

waving about in the wind, and runnels of

water coursing down the drive like little rivulets.

It was the sort of afternoon when nobody who

could help it would choose to be out, and a visitor

to the Hall seemed about the most unlikely event

on the face of the earth. Judge her surprise,

therefore, when she heard the hoot of a motor-horn,

and the next instant saw, coming up the

drive, the well-known Daimler touring car from

Cheverley Chase. In her excitement she almost

dropped her clubs. Had Cousin Clare come

over to see them? Or had Everard a holiday?

She longed to communicate the thrilling news to

Lilias, but the music was still going on, and her

arms must move in time to it. She waited in a

flutter of expectation, revolving all kinds of delightful[52]

possibilities that might occur. Cousin

Clare would surely send a cake and a box of chocolates,

even if she had not come herself. Five

minutes passed, then Davis, the parlor-maid,

opened the door, and whispered a brief message

to Miss Perkins. The mistress held up her hand

and stopped the exercises.

"Lilias and Dulcie are wanted at once in the

study," she said.

Amid the astonished looks of their companions,

the two girls put down their clubs and left the

room, Dulcie hastily telling her sister, as they

hurried down the passage, how she had seen the

car from the window. They tapped at the study

door, and entered full of pleasant anticipation.

Miss Walters was standing by the fire, with a

letter in her hand.

"Come in, girls," she said gravely. "I've

sent for you because I have something very sad

to tell you. Can you prepare your minds for a

great shock? Your Grandfather was taken ill

suddenly last night, and passed away this morning.

Your cousin has sent the car to fetch you both

home. Go at once and change your dresses, and

Miss Harvey will help you to pack a few clothes.

The chauffeur is having some tea, but you must

not keep him waiting very long. I can't tell you

how grieved I am. You must be brave girls and[53]

try to comfort every one else at home. It will be

a sad loss for you all."

Lilias and Dulcie went upstairs almost dazed

with the unexpected bad news. They could

hardly believe that their grandfather, whom they

had left apparently in the best of health and

spirits, could have gone away into that other

world where Father and Mother and a little sister

had already passed over before. They packed

in a sort of dream, drank the cups of tea which

Miss Walters, full of kind sympathy, pressed upon

them in the hall, greeted Milner, who was starting

his engine, and entered the waiting car. Owing

to the floods, they took a roundabout route,

but half an hour's drive through sleet and rain

brought them to Cheverley Chase. It was

strange to see the blinds all down as they drew

up at the house. As they ran indoors, Winder,

the old butler, came from his pantry into the hall.

They questioned him eagerly. He shook his

head as he replied:

"It's a sad business, Miss Lilias and Miss Dulcie.

He was just as usual yesterday, then about

nine o'clock Miss Clare rang the bell violently,

and when I came into the drawing-room, there

was Master lying on the floor in a kind of fit.

I telephoned to the doctor, and we got him to

bed, but he never recovered consciousness. He

went at eleven this morning, as you'll see by the[54]

clock there. I stopped all the clocks at once.

It's the right thing to do in a house when the

master dies. Miss Clare's in her room. I'll let

her know you've arrived."

"We'll go and find her, thank you," said Lilias,

walking quietly upstairs.

The Ingleton children were truly grieved at

the loss of the grandfather who, for so many

years, had stood to them in the place of a parent.

They went softly about the house and spoke in

hushed voices. Everything seemed strange and

unusual. A dressmaker came from London with

boxes of mourning for Cousin Clare and the girls;

beautiful wreaths and crosses of flowers kept arriving

and were carried upstairs. Mr. Bowden,

the lawyer, was constantly in and out, making

arrangements for the funeral; neighbors left

cards with "Kind sympathy" written across the

corner. Everard, who had arrived home shortly

after his sisters, seemed to have grown years

older. He walked with a new dignity, as of one

who is suddenly called to fill a high position.

"I'll be a good brother to you all," he said to

the younger ones. "You must always look upon

the Chase as your home, of course. I'll do

everything for you that Grandfather ever did, and

more!"

"Will the Chase be yours now, then, Everard?"

asked Bevis.

[55]"I suppose so. I'm the eldest son, you see,

and the property has always gone in the direct

line. It was entailed until fifty years ago. I

shan't make any changes. I've told the servants

so, and they all said they wished to stay on.

I wouldn't part with Winder or Milner for the

world! They're part of the establishment."

"I couldn't imagine the place without them,"

agreed Dulcie.

On the afternoon before the funeral, Mr. Bowden,

who had motored over to make some final

arrangements, concluded his business, drank a cup

of tea in the drawing-room, and was escorted by

Everard and Lilias through the hall.

"The passing of the Squire is a sad loss to the

neighborhood," he remarked. "He was a true

type of the good old school of country gentlemen,

and most of us feel 'we shall not look upon his

like again.'"

"No," replied Everard. "It will be very hard

to succeed him, I know, but I shall try to do my

best."

Mr. Bowden started, looked at him musingly

for a moment, knitted his brows, then apparently

came to a decision. Instead of taking his hat

and coat from Winder, he waved the two young

people into the study, followed them, and shut the

door.

"I want a word with you in private," he began.[56]

"I'm going to do a very unprofessional

thing, but, as I've known you for years, I feel

the case justifies me. I can't let you come into the

dining-room to-morrow, after the funeral, and

hear your grandfather's will read aloud, without

giving you some warning beforehand of its contents.

I hinted to you, Everard, at Christmas-time,

not to count too much upon expectations."

"Why, but surely I am the heir?" burst out

Everard with white lips.

"My poor boy, you are nothing of the sort.

Your grandfather has willed the property to the

child of his elder son, Tristram."

At that critical moment there was a rap at the

door, and Winder, the butler, entered, respectfully

apologetic, to summon Mr. Bowden to the

telephone. The lawyer answered the call, which

was apparently a very urgent one, for, without

another word to Everard and Lilias, he took hat

and coat, hurried from the house, mounted his

motor-cycle, and was gone. He left utter consternation

behind him. The two young people,

returning to the study, tried to face the disastrous

news. He had indeed told them no details,

but the main outline was quite sufficient. They

could scarcely accustom themselves to believe it

for a moment or two.

"To bring me up as the heir, and then disinherit

me!" gasped Everard.

[57]"Why, everybody called you 'the young

squire'!" exclaimed Lilias. "It's unthinkable!"

"Unthinkable or not, I'm afraid it's true," said

Everard bitterly. "Bowden wouldn't have told

me otherwise. I suppose he drew up the will, so

he knows what's in it. Nice position to be in,

isn't it? Turned out to make room for some

other chap!"

"Who is this child of Uncle Tristram's?

We've never heard of him."

"It'll be the kid who is in that photo, I suppose—Leslie.

He looked about a year old in

the portrait, and it's thirteen years since Uncle

Tristram died, so he's probably fourteen or so

now. To think of a kid of fourteen taking my

place here! It's monstrous!"

"Oh, Everard, what shall we do?"

"I don't know. I'm going out to think it over.

Don't say a word about it to anybody yet.

Promise me you won't!"

Everard seized his cap and waterproof, and

plunged out-of-doors into the rain. He did not

return till dinner-time. If he was silent and preoccupied

at that meal, both Cousin Clare and Dulcie

set it down as natural to his new sense of responsibility.

Lilias looked at him uneasily.

There was a hardness in his face which she had

never seen there before. She longed to catch

him alone and question him, but after dinner he[58]

purposely avoided her, and left a message that he

had gone to the stables. She would have liked to

confide in Cousin Clare, but she had given her

promise to keep the secret, and even Dulcie must

not share it yet. The girls slept in separate

rooms at home, so that when Lilias had said good

night to the family she was alone. She went to

bed, as a matter of course, but tossed about with

throbbing heart and whirling brain. Mr. Bowden's

information had effectually banished sleep.

In about an hour, when the house was absolutely

quiet, came a soft tap at her door. She jumped