The Project Gutenberg eBook of Birds, Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 1, No. 3

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Birds, Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 1, No. 3

Author: Various

Release date: September 26, 2009 [eBook #30103]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper and Anne Storer,

some images courtesy of The Internet Archive and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BIRDS, ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY, VOL. 1, NO. 3 ***

W. E. Watt, President &c.,

Fisher Building,

277 Dearborn St., Chicago, Ill.

My dear Sir:

Please accept my thanks for a copy of the first

publication of “Birds.” Please enter my name as a regular

subscriber. It is one of the most beautiful and interesting

publications yet attempted in this direction. It has other

attractions in addition to its beauty, and it must win its

way to popular favor.

Wishing the handsome little magazine abundant prosperity,

I remain

Yours very respectfully,

Please mention “BIRDS” when you write to advertisers.

[Pg 75]

LITTLE BOY BLUE.

Boys and girls, don’t you think

that is a pretty name? I came

from the warm south, where I

went last winter, to tell you that

Springtime is nearly here.

When I sing, the buds and

flowers and grass all begin to

whisper to one another, “Springtime

is coming for we heard the

Bluebird say so,” and then they

peep out to see the warm sunshine.

I perch beside them and

tell them of my long journey

from the south and how I knew

just when to tell them to come

out of their warm winter cradles.

I am of the same blue color as

the violet that shows her pretty

face when I sing, “Summer is

coming, and Springtime is here.”

I do not like the cities for

they are black and noisy and

full of those troublesome birds

called English Sparrows. I

take my pretty mate and out in

the beautiful country we find a

home. We build a nest of

twigs, grass and hair, in a box

that the farmer puts up for us

near his barn.

Sometimes we build in a hole

in some old tree and soon there

are tiny eggs in the nest. I

sing to my mate and to the good

people who own the barn. I

heard the farmer say one day,

“Isn’t it nice to hear the Bluebird

sing? He must be very

happy.” And I am, too, for by

this time there are four or five

little ones in the nest.

Little Bluebirds are like little

boys—they are always hungry.

We work hard to find enough

for them to eat. We feed them

nice fat worms and bugs, and

when their little wings are

strong enough, we teach them

how to fly. Soon they are large

enough to hunt their own food,

and can take care of themselves.

The summer passes, and when

we feel the breath of winter we

go south again, for we do not

like the cold.

THE BLUE BIRD.

I know the song that the Bluebird is singing

Out in the apple tree, where he is swinging.

Brave little fellow! the skies may be dreary,

Nothing cares he while his heart is so cheery.

Hark! how the music leaps out from his throat,

Hark! was there ever so merry a note?

Listen a while, and you’ll hear what he’s saying,

Up in the apple tree swinging and swaying.

“Dear little blossoms down under the snow,

You must be weary of winter, I know;

Hark! while I sing you a message of cheer,

Summer is coming, and springtime is here!”

“Dear little snow-drop! I pray you arise;

Bright yellow crocus! come open your eyes;

Sweet little violets, hid from the cold,

Put on our mantles of purple and gold;

Daffodils! daffodils! say, do you hear,

Summer is coming! and springtime is here!”

[Pg 76]

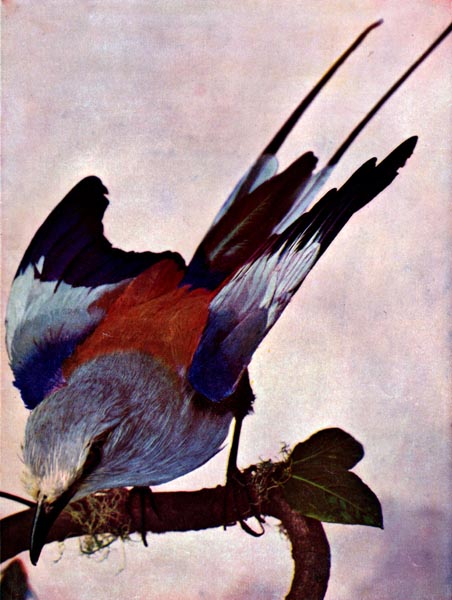

blue bird.

[Pg 78]

THE BLUE BIRD.

Winged lute that we call a blue bird,

You blend in a silver strain

The sound of the laughing waters,

The patter of spring’s sweet rain,

The voice of the wind, the sunshine,

And fragrance of blossoming things,

Ah! you are a poem of April

That God endowed with wings.E. E. R.

IKE a bit of sky this little

harbinger of spring appears,

as we see him and his mate

househunting in early

March. Oftentimes he

makes his appearance as early as the

middle of February, when his attractive

note is heard long before he himself

is seen. He is one of the last to

leave us, and although the month of

November is usually chosen by him as

the fitting time for departure to a

milder clime, his plaintive note is

quite commonly heard on pleasant

days throughout the winter season,

and a few of the braver and hardier

ones never entirely desert us. The

Robin and the Blue Bird are tenderly

associated in the memories of most

persons whose childhood was passed

on a farm or in the country village.

Before the advent of the English

Sparrow, the Blue Bird was sure to be

the first to occupy and the last to defend

the little box prepared for his return,

appearing in his blue jacket

somewhat in advance of the plainly

habited female, who on her arrival

quite often found a habitation selected

and ready for her acceptance, should

he find favor in her sight. And then

he becomes a most devoted husband

and father, sitting by the nest

and warbling with earnest affection

his exquisite tune, and occasionally flying

away in search of food for his mate

and nestlings.

The Blue Bird rears two broods in

the season, and, should the weather be

mild, even three. His nest contains

three eggs.

In the spring and summer when he

is happy and gay, his song is extremely

soft and agreeable, while it

grows very mournful and plaintive as

cold weather approaches. He is mild

of temper, and a peaceable and harmless

neighbor, setting a fine example

of amiability to his feathered friends.

In the early spring, however, he wages

war against robins, wrens, swallows,

and other birds whose habitations are

of a kind to take his fancy. A celebrated

naturalist says: “This bird

seems incapable of uttering a harsh

note, or of doing a spiteful, ill-tempered

thing.”

Nearly everybody has his anecdote

to tell of the Blue Bird’s courage, but

the author of “Wake Robin” tells

his exquisitely thus: “A few years

ago I put up a little bird house in the

back end of my garden for the accommodation

of the wrens, and every

season a pair have taken up their

abode there. One spring a pair of

Blue Birds looked into the tenement,

and lingered about several days, leading

me to hope that they would conclude

to occupy it. But they finally

went away. Late in the season the

wrens appeared, and after a little coquetting,

were regularly installed in

their old quarters, and were as happy

as only wrens can be. But before

their honeymoon was over, the Blue

Birds returned. I knew something

was wrong before I was up in the

morning. Instead of that voluble and

gushing song outside the window, I

heard the wrens scolding and crying

out at a fearful rate, and on going out

saw the Blue Birds in possession of

the box. The poor wrens were in

despair and were forced to look for

other quarters.”

[Pg 79]

THE SWALLOW.

“Come, summer visitant, attach

To my reedroof thy nest of clay,

And let my ear thy music catch,

Low twitting underneath the thatch,

At the gray dawn of day.”

URE harbingers of spring

are the Swallows. They

are very common birds,

and frequent, as a rule,

the cultivated lands in the

neighborhood of water, showing a decided

preference for the habitations of

man. “How gracefully the swallows

fly! See them coursing over the

daisy-bespangled grass fields; now

they skim just over the blades of grass,

and then with a rapid stroke of their

long wings mount into the air and

come hovering above your head, displaying

their rich white and chestnut

plumage to perfection. Now they

chase each other for very joyfulness,

uttering their sharp twittering notes;

then they hover with expanded wings

like miniature Kestrels, or dart downwards

with the velocity of the sparrowhawk;

anon they flit rapidly over

the neighboring pool, occasionally

dipping themselves in its calm and

placid waters, and leaving a long train

of rings marking their varied course.

How easily they turn, or glide over

the surrounding hedges, never resting,

never weary, and defying the eye to

trace them in the infinite turnings and

twistings of their rapid shooting flight.

You frequently see them glide rapidly

near the ground, and then with a sidelong

motion mount aloft, to dart

downwards like an animated meteor,

their plumage glowing in the light

with metallic splendor, and the row of

white spots on the tail contrasting

beautifully with the darker plumage.”

The Swallow is considered a life-paired

species, and returns to its nesting

site of the previous season, building

a new nest close to the old one.

His nest is found in barns and outhouses,

upon the beams of wood

which support the roof, or in any

place which assures protection to the

young birds. It is cup-shaped and

artfully moulded of bits of mud.

Grass and feathers are used for the

lining. “The nest completed, five or

six eggs are deposited. They are of a

pure white color, with deep rich

brown blotches and spots, notably at

the larger end, round which they

often form a zone or belt.” The sitting

bird is fed by her mate.

The young Swallow is distinguished

from the mature birds by the

absence of the elongated tail feathers,

which are a mark of maturity alone.

His food is composed entirely of insects.

Swallows are on the wing fully

sixteen hours, and the greater part of

the time making terrible havoc

amongst the millions of insects which

infest the air. It is said that when

the Swallow is seen flying high in the

heavens, it is a never failing indication

of fine weather.

A pair of Swallows on arriving at

their nesting place of the preceding

Summer found their nest occupied by

a Sparrow, who kept the poor birds at

a distance by pecking at them with

his strong beak whenever they attempted

to dislodge him. Wearied

and hopeless of regaining possession

of their property, they at last hit upon

a plan which effectually punished the

intruder. One morning they appeared

with a few more Swallows—their

mouths filled with a supply of tempered

clay—and, by their joint efforts

in a short time actually plastered up

the entrance to the hole, thus barring

the Sparrow from the home which he

had stolen from the Swallows.

[Pg 80]

barn swallow.

[Pg 82]

THE BROWN THRUSH.

“However the world goes ill,

The Thrushes still sing in it.”

HE Mocking-bird of the North,

as the Brown Thrush has

been called, arrives in the

Eastern and Middle States

about the 10th of May, at which

season he may be seen, perched on the

highest twig of a hedge, or on the

topmost branch of a tree, singing his

loud and welcome song, that may be

heard a distance of half a mile. The

favorite haunt of the Brown Thrush,

however, is amongst the bright and

glossy foliage of the evergreens.

“There they delight to hide, although

not so shy and retiring as the Blackbird;

there they build their nests in

greatest numbers, amongst the perennial

foliage, and there they draw at

nightfall to repose in warmth and

safety.” The Brown Thrasher sings

chiefly just after sunrise and before

sunset, but may be heard singing at

intervals during the day. His food

consists of wild fruits, such as blackberries

and raspberries, snails, worms,

slugs and grubs. He also obtains

much of his food amongst the withered

leaves and marshy places of the

woods and shrubberies which he

frequents. Few birds possess a more

varied melody. His notes are almost

endless in variety, each note seemingly

uttered at the caprice of the bird,

without any perceptible approach to

order.

The site of the Thrush’s nest is a

varied one, in the hedgerows, under a

fallen tree or fence-rail; far up in the

branches of stately trees, or amongst

the ivy growing up their trunks. The

nest is composed of the small dead

twigs of trees, lined with the fine

fibers of roots. From three to five

eggs are deposited, and are hatched

in about twelve days. They have a

greenish background, thickly spotted

with light brown, giving the whole

egg a brownish appearance.

The Brown Thrush leaves the Eastern

and Middle States, on his migration

South, late in September, remaining

until the following May.

[Pg 83]

THE THRUSH’S NEST.

“Within a thick and spreading hawthorn bush

That overhung a molehill, large and round,

I heard from morn to morn a merry thrush

Sing hymns of rapture while I drank the sound

With joy—and oft an unintruding guest,

I watched her secret toils from day to day;

How true she warped the moss to form her nest,

And modeled it within with wood and clay.

And by and by, with heath-bells gilt with dew,

There lay her shining eggs as bright as flowers,

Ink-spotted over, shells of green and blue:

And there I witnessed, in the summer hours,

A brood of nature’s minstrels chirp and fly,

Glad as the sunshine and the laughing sky.”

THE BROWN THRUSH.

Dear Readers:

My cousin Robin Redbreast

told me that he wrote you a

letter last month and sent it

with his picture. How did you

like it? He is a pretty bird—Cousin

Robin—and everybody

likes him. But I must tell you

something of myself.

Folks call me by different

names—some of them nicknames,

too.

The cutest one of all is Brown

Thrasher. I wonder if you

know why they call me Thrasher.

If you don’t, ask some one. It

is really funny.

Some people think Cousin

Robin is the sweetest singer of

our family, but a great many

like my song just as well.

Early in the morning I sing

among the bushes, but later in

the day you will always find me

in the very top of a tree and it

is then I sing my best.

Do you know what I say in

my song? Well, if I am near a

farmer while he is planting, I

say: “Drop it, drop it—cover it

up, cover it up—pull it up, pull

it up, pull it up.”

One thing I very seldom do

and that is, sing when near my

nest. Maybe you can tell why.

I’m not very far from my nest

now. I just came down to the

stream to get a drink and am

watching that boy on the other

side of the stream. Do you see

him?

One dear lady who loves birds

has said some very nice things

about me in a book called “Bird

Ways.” Another lady has

written a beautiful poem about

my singing. Ask your mamma or

teacher the names of these

ladies. Here is the poem:

There’s a merry brown thrush sitting up in a tree.

He is singing to me! He is singing to me!

And what does he say—little girl, little boy?

“Oh, the world’s running over with joy!

Hush! Look! In my tree,

I am as happy as happy can be.”

And the brown thrush keeps singing, “A nest, do you see,

And five eggs, hid by me in the big cherry tree?

Don’t meddle, don’t touch—little girl, little boy—

Or the world will lose some of its joy!

Now I am glad! now I am free!

And I always shall be,

If you never bring sorrow to me.”

So the merry brown thrush sings away in the tree

To you and to me—to you and to me;

And he sings all the day—little girl, little boy—

“Oh, the world’s running over with joy!

But long it won’t be,

Don’t you know? don’t you see?

Unless we’re good as good can be.”

[Pg 84]

brown thrasher.

[Pg 86]

japan pheasant.

[Pg 88]

THE JAPAN PHEASANT.

RIGINALLY the Pheasant

was an inhabitant of Asia

Minor but has been by degrees

introduced into many

countries, where its beauty

of form, plumage, and the delicacy of

its flesh made it a welcome visitor.

The Japan Pheasant is a very beautiful

species, about which little is

known in its wild state, but in captivity

it is pugnacious. It requires

much shelter and plenty of food, and

the breed is to some degree artificially

kept up by the hatching of eggs under

domestic hens and feeding them

in the coop like ordinary chickens,

until they are old and strong enough

to get their own living.

The food of this bird is extremely

varied. When young it is generally

fed on ants’ eggs, maggots,

grits, and similar food, but when it is

full grown it is possessed of an accommodating

appetite and will eat many

kinds of seeds, roots, and leaves. It

will also eat beans, peas, acorns, berries,

and has even been known to eat

the ivy leaf, as well as the berry.

This Pheasant loves the ground,

runs with great speed, and always prefers

to trust to its legs rather than to its

wings. It is crafty, and when alarmed

it slips quickly out of sight behind a

bush or through a hedge, and then

runs away with astonishing rapidity,

always remaining under cover until it

reaches some spot where it deems itself

safe. The male is not domestic,

passing an independent life during

a part of the year and associating

with others of its own sex during the

rest of the season.

The nest is very rude, being merely

a heap of leaves and grass on the

ground, with a very slight depression.

The eggs are numerous, about eleven

or twelve, and olive brown in color. In

total length, though they vary considerably,

the full grown male is about

three feet. The female is smaller in

size than her mate, and her length

a foot less.

The Japan Pheasant is not a particularly

interesting bird aside from his

beauty, which is indeed brilliant, there

being few of the species more attractive.

[Pg 89]

THE FLICKER.

GREAT variety of names

does this bird possess. It

is commonly known as the

Golden Winged Woodpecker,

Yellow-shafted Flicker, Yellow

Hammer, and less often as High-hole

or High-holer, Wake-up, etc. In suitable

localities throughout the United

States and the southern parts of Canada,

the Flicker is a very common

bird, and few species are more generally

known. “It is one of the most

sociable of our Woodpeckers, and is

apparently always on good terms with

its neighbors. It usually arrives in

April, occasionally even in March, the

males preceding the females a few

days, and as soon as the latter appear

one can hear their voices in all directions.”

The Flicker is an ardent wooer. It

is an exceedingly interesting and

amusing sight to see a couple of males

paying their addresses to a coy and

coquettish female; the apparent shyness

of the suitors as they sidle up to

her and as quickly retreat again, the

shy glances given as one peeps from

behind a limb watching the other—playing

bo-peep—seem very human,

and “I have seen,” says an observer,

“few more amusing performances than

the courtship of a pair of these birds.”

The defeated suitor takes his rejection

quite philosophically, and retreats in a

dignified manner, probably to make

other trials elsewhere. Few birds

deserve our good will more than the

Flicker. He is exceedingly useful,

destroying multitudes of grubs, larvæ,

and worms. He loves berries and

fruit but the damage he does to cultivated

fruit is very trifling.

The Flicker begins to build its nest

about two weeks after the bird arrives

from the south. It prefers open country,

interspersed with groves and orchards,

to nest in. Any old stump, or

partly decayed limb of a tree, along

the banks of a creek, beside a country

road, or in an old orchard, will answer

the purpose. Soft wood trees seem to

be preferred, however. In the prairie

states it occasionally selects strange

nesting sites. It has been known to

chisel through the weather boarding of

a dwelling house, barns, and other buildings,

and to nest in the hollow space

between this and the cross beams; its

nests have also been found in gate

posts, in church towers, and in burrows

of Kingfishers and bank swallows, in

perpendicular banks of streams. One

of the most peculiar sites of his selection

is described by William A. Bryant

as follows: “On a small hill, a

quarter of a mile distant from any

home, stood a hay stack which had

been placed there two years previously.

The owner, during the winter of

1889-90, had cut the stack through the

middle and hauled away one portion,

leaving the other standing, with the

end smoothly trimmed. The following

spring I noticed a pair of flickers about

the stack showing signs of wanting to

make it a fixed habitation. One morning

a few days later I was amused at

the efforts of one of the pair. It was

clinging to the perpendicular end of

the stack and throwing out clipped

hay at a rate to defy competition.

This work continued for a week, and

in that time the pair had excavated a

cavity twenty inches in depth. They

remained in the vicinity until autumn.

During the winter the remainder of

the stack was removed. They returned

the following spring, and, after

a brief sojourn, departed for parts unknown.”

From five to nine eggs are generally

laid. They are glossy white in color,

and when fresh appear as if enameled.

The young are able to leave the

nest in about sixteen days; they crawl

about on the limbs of the tree for a

couple of days before they venture to

fly, and return to the nest at night.

[Pg 90]

flicker.

[Pg 92]

THE BOBOLINK.

“When Nature had made all her birds,

And had no cares to think on,

She gave a rippling laugh,

And out there flew a Bobolinkon.”

O American ornithologist

omits mention of the Bobolink,

and naturalists generally

have described

him under one of the

many names by which he is known.

In some States he is called the Rice

Bird, in others Reed Bird, the Rice or

Reed Bunting, while his more familiar

title, throughout the greater part of

America, is Bobolink, or Bobolinkum.

In Jamaica, where he gets very fat

during his winter stay, he is called the

Butter Bird. His title of Rice

Troopial is earned by the depredations

which he annually makes upon the

rice crops, though his food “is by no

means restricted to that seed, but consists

in a large degree of insects, grubs,

and various wild grasses.” A migratory

bird, residing during the winter

in the southern parts of America, he

returns in vast multitudes northward

in the early Spring. According to

Wilson, their course of migration is as

follows: “In April, or very early in

May, the Rice Buntings, male and

female, arrive within the southern

boundaries of the United States, and

are seen around the town of Savannah,

Georgia, sometimes in separate

parties of males and females, but

more generally promiscuously. They

remain there but a short time, and

about the middle of May make their

appearance in the lower part of

Pennsylvania. While here the males

are extremely gay and full of song,

frequenting meadows, newly plowed

fields, sides of creeks, rivers, and

watery places, feeding on May flies

and caterpillars, of which they destroy

great quantities. In their passage,

however, through Virginia at this season,

they do great damage to the early

wheat and barley while in their milky

state. About the 20th of May they

disappear on their way to the North.

Nearly at the same time they arrive in

the State of New York, spread over

the whole of the New England

States, as far as the river St. Lawrence,

and from Lake Ontario to the

sea. In all of these places they remain

during the Summer, building

their nests and rearing their young.”

The Bobolink’s song is a peculiar

one, varying greatly with the occasion.

As he flys southward, his cry is

a kind of clinking note; but the love

song addressed to his mate is voluble

and fervent. It has been said that if

you should strike the keys of a pianoforte

haphazard, the higher and the

lower singly very quickly, you might

have some idea of the Bobolink’s

notes. In the month of June he

gradually changes his pretty, attractive

dress and puts on one very like

the females, which is of a plain rusty

brown, and is not reassumed until the

next season of nesting. The two parent

birds in the plate represent the

change from the dark plumage in

which the bird is commonly known

in the North as the Bobolink, to the

dress of yellowish brown by which it

is known throughout the South as the

Rice or Reed Bird.

His nest, small and a plain one, too,

is built on the ground by his industrious

little wife. The inside is warmly

lined with soft fibers of whatever may

be nearest at hand. Five pretty white

eggs, spotted all over with brown are

laid, and as soon

“As the little ones chip the shell

And five wide mouths are ready for food,

‘Robert of Lincoln’ bestirs him well,

Gathering seeds for this hungry brood.”

[Pg 93]

BOBOLINK.

Other birds may like to travel

alone, but when jolly Mr. Bobolink

and his quiet little wife

come from the South, where they

have spent the winter, they

come with a large party of

friends. When South, they eat

so much rice that the people call

them Rice Birds. When they

come North, they enjoy eating

wheat, barley, oats and insects.

Mr. and Mrs. Bobolink build

their simple little nest of grasses

in some field. It is hard to find

on the ground, for it looks just

like dry grass. Mrs. Bobolink

wears a dull dress, so she cannot

be seen when she is sitting on

the precious eggs. She does

not sing a note while caring

for the eggs. Why do you

think that is?

Mr. Bob-Linkum does not

wear a sober dress, as you can

see by his picture. He does not

need to be hidden. He is just

as jolly as he looks. Shall I

tell you how he amuses his mate

while she is sitting? He springs

from the dew-wet grass with a

sound like peals of merry laughter.

He frolics from reed to

post, singing as if his little

heart would burst with joy.

Don’t you think Mr. and Mrs.

Bobolink look happy in the

picture? They have raised

their family of five. Four of

their children have gone to look

for food; one of them—he must

surely be the baby—would

rather stay with his mamma and

papa. Which one does he look

like?

Many birds are quiet at noon

and in the afternoon. A flock

of Bobolinks can be heard singing

almost all day long. The

song is full of high notes and

low, soft notes and loud, all

sung rapidly. It is as gay and

bright as the birds themselves,

who flit about playfully as they

sing. You will feel like laughing

as merrily as they sing when

you hear it some day.

[Pg 94]

bobolinks.

[Pg 96]

THE BLUE BIRD.

“Drifting down the first warm wind

That thrills the earliest days of spring,

The Bluebird seeks our maple groves

And charms them into tasselling.”

“He sings, and his is Nature’s voice—

A gush of melody sincere

From that great fount of harmony

Which thaws and runs when Spring is here.”

“Short is his song, but strangely sweet

To ears aweary of the low

Dull tramps of Winter’s sullen feet,

Sandalled in ice and muffled in snow.”

“Think, every morning, when the sun peeps through

The dim, leaf-latticed windows of the grove,

How jubilant the happy birds renew

Their old, melodious madrigals of love!

And when you think of this, remember, too,

’Tis always morning somewhere, and above

The awakening continents, from shore to shore,

Somewhere the birds are singing evermore.

“Think of your woods and orchards without birds!

Of empty nests that cling to boughs and beams

As in an idiot’s brain remembered words

Hang empty ’mid the cobwebs of his dreams!

Will bleat of flocks or bellowing of herds

Make up for the lost music, when your teams

Drag home the stingy harvest, and no more

The feathered gleaners follow to your door?”

From “The Birds of Killingsworth.”

[Pg 97]

THE CROW.

Caw! Caw! Caw! little boys

and girls. Caw! Caw! Caw!

Just look at my coat of feathers.

See how black and glossy it is.

Do you wonder I am proud of it?

Perhaps you think I look very

solemn and wise, and not at all

as if I cared to play games. I

do, though; and one of the

games I like best is hide-and-seek.

I play it with the farmer

in the spring. He hides, in the

rich, brown earth, golden kernels

of corn. Surely he does it because

he knows I like it, for

sometimes he puts up a stick all

dressed like a man to show

where the corn is hidden. Sometimes

I push my bill down into

the earth to find the corn, and at

other times I wait until tiny

green leaves begin to show above

the ground, and then I get my

breakfast without much trouble.

I wonder if the farmer enjoys

this game as much as I do. I

help him, too, by eating worms

and insects.

During the spring and summer

I live in my nest on the top

of a very high tree. It is built

of sticks and grasses and straw

and string and anything else I

can pick up. But in the fall, I

and all my relations and friends

live together in great roosts or

rookeries. What good times

we do have—hunting all day

for food and talking all night.

Wouldn’t you like to be with us?

The farmer who lives in the

house over there went to the mill

to-day with a load of corn.

One of the ears dropped out

of the wagon and it didn’t take

me long to find it. I have eaten

all I can possibly hold and am

wondering now what is the best

thing to do. If you were in my

place would you leave it here

and not tell anybody and come

back to-morrow and finish it? Or

would you fly off and get Mrs.

Crow and some of the children

to come and finish it? I believe

I’ll fly and get them. Good-bye.

Caw! Caw! Caw!

[Pg 98]

common crow.

[Pg 100]

THE COMMON CROW.

“The crow doth sing as merry as the lark,

When neither is attended.”

EW birds have more interesting

characteristics than the Common

Crow, being, in many of

his actions, very like the

Raven, especially in his love for

carrion. Like the Raven, he has been

known to attack game, although his

inferior size forces him to call to his

assistance the aid of his fellows to cope

with larger creatures. Rabbits and

hares are frequently the prey of this

bird which pounces on them as

they steal abroad to feed. His

food consists of reptiles, frogs, and

lizards; he is a plunderer of other

birds’ nests. On the seashore he finds

crabs, shrimps and inhabited shells,

which he ingeniously cracks by flying

with them to a great height and

letting them fall upon a convenient

rock.

The crow is seen in single pairs or

in little bands of four or five. In the

autumn evenings, however, they

assemble in considerable flocks before

going to roost and make a wonderful

chattering, as if comparing notes of

the events of the day.

The nest of the Crow is placed in

some tree remote from habitations of

other birds. Although large and

very conspicuous at a distance, it is

fixed upon one of the topmost branches

quite out of reach of the hand of the

adventurous urchin who longs to

secure its contents. It is loosely made

and saucer shaped. Sticks and softer

substances are used to construct it,

and it is lined with hair and fibrous

roots. Very recently a thrifty and

intelligent Crow built for itself a

summer residence in an airy tree near

Bombay, the material used being gold,

silver, and steel spectacle frames,

which the bird had stolen from an

optician of that city. Eighty-four

frames had been used for this purpose,

and they were so ingeniously woven

together that the nest was quite a

work of art. The eggs are variable,

or rather individual, in their markings,

and even in their size. The Crow

rarely uses the same nest twice,

although he frequently repairs to the

same locality from year to year. He

is remarkable for his attachment to

his mate and young, surpassing the

Fawn and Turtle Dove in conjugal

courtesy.

The Somali Arabs bear a deadly

hatred toward the Crow. The origin

of their detestation is the superstition

that during the flight of Mohammed

from his enemies, he hid himself in a

cave, where he was perceived by the

Crow, at that time a bird of light

plumage, who, when he saw the pursuers

approaching the spot, perched

above Mohammed’s hiding place, and

screamed, “Ghar! Ghar!” (cave! cave!)

so as to indicate the place of concealment.

His enemies, however, did not

understand the bird, and passed on,

and Mohammed, when he came out of

the cave, clothed the Crow in perpetual

black, and commanded him to

cry “Ghar” as long as Crows should

live.

And he lives to a good old age.

Instances are not rare where he has

attained to half a century, without

great loss of activity or failure of sight.

At Red Bank, a few miles northeast

of Cincinnati, on the Little Miami

River, in the bottoms, large flocks of

Crows congregate the year around. A

few miles away, high upon Walnut

Hills, is a Crow roost, and in the

late afternoons the Crows, singly, in

pairs, and in flocks, are seen on the

wing, flying heavily, with full crops,

on the way to the roost, from which

they descend in the early morning,

crying “Caw! Caw!” to the fields of

the newly planted, growing, or

matured corn, or corn stacks, as the

season may provide.

[Pg 101]

THE RETURN OF THE BIRDS.

“Everywhere the blue sky belongs to them and is their appointed rest,

and their native country, and their own natural home which they enter

unannounced as lords that are certainly expected, and yet there is a

silent joy at their arrival.”

HE return of the birds to their

real home in the North, where

they build their nests and

rear their young, is regarded

by all genuine lovers of earth’s messengers

of gladness and gayety as one

of the most interesting and poetical of

annual occurrences. The naturalist,

who notes the very day of each arrival,

in order that he may verify former

observation or add to his material

gathered for a new work, does not

necessarily anticipate with greater

pleasure this event than do many

whose lives are brightened by the

coming of the friends of their youth,

who alone of early companions do not

change. First of all—and ever the

same delightful warbler—the Bluebird,

who, in 1895, did not appear at

all in many localities, though here in

considerable numbers last year, betrays

himself. “Did he come down out

of the heaven on that bright March

morning when he told us so softly and

plaintively that, if we pleased, spring

had come?” Sometimes he is here

a little earlier, and must keep his

courage up until the cold snap is over

and the snow is gone. Not long after

the Bluebird, comes the Robin, sometimes

in March, but in most of the

northern states April is the month of

his arrival. With his first utterance

the spell of winter is broken, and the

remembrance of it afar off. Then

appears the Woodpecker in great

variety, the Flicker usually arriving

first. He is always somebody’s old

favorite, “announcing his arrival by a

long, loud call, repeated from the dry

branch of some tree, or a stake in the

fence—a thoroughly melodious April

sound.”

Few perhaps reflect upon the difficulties

encountered by the birds themselves

in their returning migrations.

A voyager sometimes meets with

many of our common birds far out at

sea. Such wanderers, it is said, when

suddenly overtaken by a fog, completely

lose their sense of direction

and become hopelessly lost. Humming

birds, those delicately organized,

glittering gems, are among the most

common of the land species seen at sea.

The present season has been quite

favorable to the protection of birds.

A very competent observer says that

not all of the birds migrated this

winter. He recently visited a farm

less than an hour’s ride from Chicago,

where he found the old place, as he

relates it, “chucked full of Robins,

Blackbirds, and Woodpeckers,” and

others unknown to him. From this

he inferred they would have been in

Florida had indications predicted a

severe winter. The trees of the south

parks of Chicago, and those in

suburban places, have had, darting

through their branches during the

months of December and January,

nearly as many members of the Woodpecker

tribe as were found there

during the mating season in May last.

Alas, that the Robin will visit us in

diminished numbers in the approaching

spring. He has not been so common

for a year or two as he was

formerly, for the reason that the

Robins died by thousands of starvation,

owing to the freezing of their food

supply in Tennessee during the protracted

cold weather in the winter of

1895. It is indeed sad that this good

Samaritan among birds should be

defenseless against the severity of

Nature, the common mother of us all.

Nevertheless the return of the birds,

in myriads or in single pairs, will

be welcomed more and more, year by

year, as intelligent love and appreciation

of them shall possess the popular

mind.

[Pg 103]

black tern.

Mother and Young with Eggs.

[Pg 104]

THE BLACK TERN.

HE TERN,” says Mr. F. M.

Woodruff, of the Chicago

Academy of Sciences, “is

the only representative of

the long-winged swimmers which

commonly nests with us on our

inland fresh water marshes, arriving

early in May in its brooding plumage

of sooty black. The color changes

in the autumn to white, and a number

of the adult birds may be found, in

the latter part of July, dotted and

streaked here and there with white.

On the first of June, 1891, I found a

large colony of Black Terns nesting

on Hyde Lake, Cook County, Illinois.

As I approached the marsh a few

birds were seen flying high in the air,

and, as I neared the nesting site, the

flying birds gave notes of alarm, and

presently the air was filled with the

graceful forms of this beautiful little

bird. They circled about me, darting

down to within a few feet of my head,

constantly uttering a harsh, screaming

cry. As the eggs are laid upon the

bare ground, which the brownish and

blackish markings so closely resemble,

I was at first unable to find the nests,

and discovered that the only way to

locate them was to stand quietly and

watch the birds. When the Tern is

passing over the nest it checks its

flight, and poises for a moment on

quivering wings. By keeping my

eyes on this spot I found the nest

with very little trouble. The complement

of eggs, when the bird has not

been disturbed, is usually three.

These are laid in a saucer shaped

structure of dead vegetation, which is

scraped together, from the surface of

the wet, boggy ground. The bird

figured in the plate had placed its

nest on the edge of an old muskrat

house, and my attention was attracted

to it by the fact that upon the edge of

the rat house, where it had climbed to

rest itself, was the body of a young

dabchick, or piedbilled grebe, scarcely

two and one-half inches long, and not

twenty-four hours out of the egg, a

beautiful little ball of blackish down,

striped with brown and white. From

the latter part of July to the middle of

August large flocks of Black Terns

may be seen on the shores of our

larger lakes on their annual migration

southward.”

The Rev. P. B. Peabody, in alluding to

his observation of the nests of the

Tern, says: “Amid this floating sea

of aquatic nests I saw an unusual

number of well constructed homes of

the Tern. Among these was one that

I count a perfect nest. It rested on

the perfectly flat foundation of a small

decayed rat house, which was about

fourteen inches in diameter. The nest,

in form, is a truncated cone (barring the

cavity), was about eight inches high

and ten inches in diameter. The

hollow—quite shallow—was about

seven inches across, being thus unusually

large. The whole was built

up of bits of rushes, carried to the spot,

these being quite uniform in length—about

four inches.” After daily

observation of the Tern, during which

time he added much to his knowledge

of the bird, he pertinently asks: “Who

shall say how many traits and habits

yet unknown may be discovered

through patient watching of community-breeding

birds, by men enjoying

more of leisure for such delightful

studies than often falls to the lot of

most of us who have bread and butter

to earn and a tiny part of the world’s

work to finish?”

[Pg 105]

THE MEADOW LARK.

“Not an inch of his body is free from delight.

Can he keep himself still if he would? Oh, not he!

The music stirs in him like wind through a tree.”

HE well known Meadow or

Old Field Lark is a constant

resident south of latitude

39, and many winter

farther north in favorite localities.

Its geographical range is eastern

North America, Canada to south Nova

Scotia, Quebec, and Ontario to eastern

Manitoba; west to Minnesota, Iowa,

Missouri, eastern Kansas, the Indian

Territory, and Texas; south to Florida

and the Gulf coast, in all of which

localities, except in the extreme north,

it usually rears two or three broods in

a season. In the Northern States it

is only a summer resident, arriving in

April and remaining until the latter

part of October and occasionally

November. Excepting during the

breeding season, small flocks may

often be seen roving about in search

of good feeding grounds. Major Bendire

says this is especially true in the

fall of the year. At this time several

families unite, and as many as two

dozen may occasionally be flushed in

a field, over which they scatter, roaming

about independently of each other.

When one takes wing all the others

in the vicinity follow. It is a shy

bird in the East, while in the middle

states it is quite the reverse. Its flight

is rather laborious, at least in starting,

and is continued by a series of rapid

movements of the wings, alternating

with short distances of sailing, and is

rarely protracted. On alighting, which

is accompanied with a twitching of its

tail, it usually settles on some fence

rail, post, boulder, weedstock, or on

a hillock in a meadow from which it

can get a good view of the surroundings,

and but rarely on a limb of a

tree. Its favorite resorts are meadows,

fallow fields, pastures, and clearings,

but in some sections, as in northern

Florida, for instance, it also frequents the

low, open pine woods and nests there.

The song of the Meadow Lark is

not much varied, but its clear, whistling

notes, so frequently heard in the

early spring, are melodious and pleasing

to the ear. It is decidedly the

farmers’ friend, feeding, as it does, on

noxious insects, caterpillars, moths,

grasshoppers, spiders, worms and the

like, and eating but little grain. The

lark spends the greater part of its

time on the ground, procuring all its

food there. It is seldom found alone,

and it is said remains paired for life.

Nesting begins in the early part of

May and lasts through June. Both

sexes assist in building the nest, which

is always placed on the ground, either

in a natural depression, or in a little

hollow scratched out by the birds,

alongside a bunch of grass or weeds.

The nest itself is lined with dry grass,

stubble, and sometimes pine needles.

Most nests are placed in level meadows.

The eggs and young are frequently

destroyed by vermin, for the meadow

lark has many enemies. The eggs

vary from three to seven, five being

the most common, and both sexes assist

in the hatching, which requires

about fifteen or sixteen days. The

young leave the nest before they are

able to fly—hiding at the slightest

sign of danger. The Meadow Lark

does not migrate beyond the United

States. It is a native bird, and is only

accidental in England. The eggs

are spotted, blotched, and speckled

with shades of brown, purple and

lavender. A curious incident is told

of a Meadow Lark trying to alight on

the top mast of a schooner several

miles at sea. It was evidently very tired

but would not venture near the deck.

[Pg 106]

meadow lark.

[Pg 108]

THE MEADOW LARK.

I told the man who wanted

my picture that he could take it

if he would show my nest and

eggs. Do you blame me for

saying so? Don’t you think it

makes a better picture than if I

stood alone?

Mr. Lark is away getting me

some breakfast, or he could be

in the picture, too. After a few

days I shall have some little

baby birds, and then won’t we

be happy.

Boys and girls who live in the

country know us pretty well.

When they drive the cows out

to pasture, or when they go out

to gather wild flowers, we sit on

the fences by the roadside and

make them glad with our merry

song.

Those of you who live in the

city cannot see us unless you

come out into the country.

It isn’t very often that we can

find such a pretty place for a

nest as we have here. Most of

the time we build our nest under

the grass and cover it over, and

build a little tunnel leading to

it. This year we made up our

minds not to be afraid.

The people living in the houses

over there do not bother us at all

and we are so happy.

You never saw baby larks,

did you? Well, they are queer

little fellows, with hardly any

feathers on them.

Last summer we had five little

birdies to feed, and it kept us

busy from morning till night.

This year we only expect three,

and Mr. Lark says he will do all

the work. He knows a field

that is being plowed, where he

can get nice, large worms.

Hark! that is he singing.

He will be surprised when he

comes back and finds me off the

nest. He is so afraid that I will

let the eggs get cold, but I

won’t. There he comes, now.

[Pg 109]

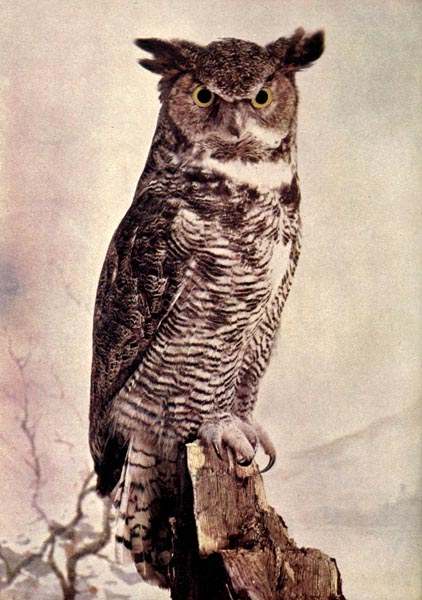

THE LONG-EARED OWL.

HE name of the Long-Eared

Owl is derived from the great

length of his “ears” or feather-tufts,

which are placed upon

the head, and erect themselves whenever

the bird is interested or excited.

It is the “black sheep” of the owl

family, the majority of owls being

genuine friends of the agriculturist,

catching for his larder so many of

the small animals that prey upon

his crops. In America he is called

the Great Horned Owl—in Europe

the Golden Owl.

Nesting time with the owl begins

in February, and continues through

March and April. The clown-like

antics of both sexes of this bird while

under the tender influence of the

nesting season tend somewhat to impair

their reputation for dignity and

wise demeanor. They usually have a

simple nest in a hollow tree, but

which seems seldom to be built by the

bird itself, as it prefers to take the

deserted nest of some other bird, and

to fit up the premises for its own use.

They repair slightly from year to year

the same nest. The eggs are white,

and generally four or five in number.

While the young are still in the nest,

the parent birds display a singular

diligence in collecting food for them.

If you should happen to know of an

owl’s nest, stand near it some evening

when the old birds are rearing their

young. Keep quiet and motionless,

and notice how frequently the old

birds feed them. Every ten minutes

or so the soft flap, flap of their wings

will be heard, the male and female

alternately, and you will obtain a brief

glimpse of them through the gloom as

they enter the nesting place. They

remain inside but a short time, sharing

the food equally amongst their brood,

and then are off again to hunt for

more. All night, were you to have

the inclination to observe them, you

would find they pass to and fro with

food, only ceasing their labors at dawn.

The young, as soon as they reach

maturity, are abandoned by their

parents; they quit the nest and seek

out haunts elsewhere, while the old

birds rear another, and not infrequently

two more broods, during the remainder

of the season.

The habits of the Long-Eared Owl

are nocturnal. He is seldom seen

in the light of day, and is greatly disturbed

if he chance to issue from

his concealment while the sun is

above the horizon. The facial disk is

very conspicuous in this species. It is

said that the use of this circle is to

collect the rays of light, and throw

them upon the eye. The flight of the

owl is softened by means of especially

shaped, recurved feather-tips, so that

he may noiselessly steal upon his

prey, and the ear is also so shaped as

to gather sounds from below.

The Long-Eared Owl is hardly

tameable. The writer of this paragraph,

when a boy, was the possessor,

for more than a year, of a very fine

specimen. We called him Judge. He

was a monster, and of perfect plumage.

Although he seemed to have some

attachment to the children of the

family who fed him, he would not

permit himself to be handled by them

or by any one in the slightest. Most

of his time he spent in his cage, an

immense affair, in which he was very

comfortable. Occasionally he had

a day in the barn with the rats and

mice.

The owl is of great usefulness to

gardener, agriculturist, and landowner

alike, for there is not another bird of

prey which is so great a destroyer of

the enemies of vegetation.

[Pg 111]

great horned owl.

[Pg 112]

THE OWL.

We know not alway

Who are kings by day,

But the king of the night is the bold brown owl!

I wonder why the folks put

my picture last in the book. It

can’t be because they don’t like

me, for I’m sure I never bother

them. I don’t eat the farmer’s

corn like the crow, and no one

ever saw me quarrel with other

birds.

Maybe it is because I can’t

sing. Well, there are lots of

good people that can’t sing, and

so there are lots of good birds

that can’t sing.

Did you ever see any other

bird sit up as straight as I do?

I couldn’t sit up so straight if I

hadn’t such long, sharp claws to

hold on with.

My home is in the woods.

Here we owls build our nests—most

always in hollow trees.

During the day I stay in the

nest or sit on a limb. I don’t

like day time for the light hurts

my eyes, but when it begins to

grow dark then I like to stir

around. All night long I am

wide awake and fly about getting

food for my little hungry ones.

They sleep most of the day

and it keeps me busy nearly

all night to find them enough to

eat.

I just finished my night’s work

when the man came to take my

picture. It was getting light

and I told him to go to a large

stump on the edge of the woods

and I would sit for my picture.

So here I am. Don’t you think

I look wise? How do you like

my large eyes? If I could smile

at you I would, but my face

always looks sober. I have a

great many cousins and if you

really like my picture, I’ll have

some of them talk to you next

month. I don’t think any of

them have such pretty feathers

though. Just see if they have

when they come.

Well, I must fly back to my

perch in the old elm tree. Good-bye.

THE OWL.

In the hollow tree, in the old gray tower,

The spectral owl doth dwell;

Dull, hated, despised in the sunshine hour,

But at dusk he’s abroad and well!

Not a bird of the forest e’er mates with him;

All mock him outright by day;

But at night, when the woods grow still and dim,

The boldest will shrink away!

O! when the night falls, and roosts the fowl,

Then, then, is the reign of the Horned Owl!

And the owl hath a bride, who is fond and bold,

And loveth the wood’s deep gloom;

And, with eyes like the shine of the moonstone cold,

She awaiteth her ghastly groom.

Not a feather she moves, not a carol she sings,

As she waits in her tree so still,

But when her heart heareth his flapping wings,

She hoots out her welcome shrill!

O! when the moon shines, and dogs do howl,

Then, then, is the joy of the Horned Owl!

Mourn not for the owl, nor his gloomy plight!

The owl hath his share of good—

If a prisoner he be in the broad daylight,

He is lord in the dark greenwood!

Nor lonely the bird, nor his ghastly mate,

They are each unto each a pride;

Thrice fonder, perhaps, since a strange, dark fate

Hath rent them from all beside!

So, when the night falls, and dogs do howl,

Sing, Ho! for the reign of the Horned Owl!

We know not alway

Who are kings by day,

But the King of the Night is the bold Brown Owl!

Bryan W. Procter

(Barry Cornwall.)

TESTIMONIALS.

Frankfort, Ky., February 3, 1897.

W. J. Black, Vice-President,

Chicago, Ill.

Dear Sir: I have a copy of your magazine entitled “Birds,” and beg to

say that I consider it one of the finest things on the subject that I

have ever seen, and shall be pleased to recommend it to county and city

superintendents of the state.

Very respectfully,

W. J. Davidson,

State Superintendent Public Instruction.

San Francisco, Cal., January 27, 1897.

W. J. Black, Esq.,

Chicago, Ill.

Dear Sir: I am very much obliged for the copy of “Birds” that has just

come to hand. It should be in the hands of every primary and grammar

teacher. I send herewith copy of “List of San Francisco Teachers.”

Very respectfully,

M. Babcock.

Lincoln, Neb., February 9, 1897.

W. J. Black,

Chicago, Ill.

Dear Sir: The first number of your magazine, “Birds,” is upon my desk.

I am highly pleased with it. It will prove a very serviceable

publication—one that strikes out along the right lines. For the purpose

intended, it has, in my opinion, no equal. It is clear, concise, and

admirably illustrated.

Very respectfully,

W. R. Jackson,

State Superintendent Public Instruction.

North Lima, Ohio, February 1, 1897.

Mr. W. E. Watt,

Dear Sir: Sample copy of “Birds” received. All of the family delighted

with it. We wish it unbounded success. It will be an excellent supplement

to “In Birdland” in the Ohio Teachers’ Reading Circle, and I venture Ohio

will be to the front with a good subscription list. I enclose list of

teachers.

Very truly,

C. M. L. Altdoerffer,

Township Superintendent.

Milwaukee, January 30, 1897.

Nature Study Publishing Company,

227 Dearborn Street, Chicago.

Gentlemen: I acknowledge with pleasure the receipt of your publication,

“Birds,” with accompanying circulars. I consider it the best on the subject

in existence. I have submitted the circulars and publication to my teachers,

who have nothing to say but praise in behalf of the monthly.

Julius Torney,

Principal 2nd Dist. Primary School, Milwaukee, Wis.

Featured Books

A New Subspecies of Wood Rat (Neotoma mexicana) from Colorado

Robert B. Finley

slightly larger, but cannotbe distinguished by coloration of the pelage.This heretofore undescribed...

A Taxonomic Revision of the Leptodactylid Frog Genus Syrrhophus Cope

John D. Lynch

efinedgenus.With the exception of Taylor (1952), who treated the Costa Ricanspecies, none of these a...

The Most Sentimental Man

Evelyn E. Smith

ns. "Sure you won'tchange your mind and comewith us?"Johnson shook his head.The young man looked ath...

Prologue to an Analogue

Leigh Richmond

orld, would find that the epidemic wascaused by laboratory-developed bacteria, carried in by anAmeri...

Mr. Punch on Tour: The Humour of Travel at Home and Abroad

PUBLISHED BY ARRANGEMENT WITH THE PROPRIETORS OF "PUNCH"THE EDUCATIONAL BOOK CO. LTD.THE PUNCH LIBRA...

Atom Drive

Charles L. Fontenay

the Marsward XVIII."Something like that," agreed Jonner, and his smile broadened. "And Ihave only ab...

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

Cory Doctorow

giving away ebooks displaces the occasional sale, when a downloader reads the book and decides not t...

The Cosmic Computer

H. Beam Piper

y rated amongreaders for his skill and imagination. He has had several novelspublished, including my...

Browse by Category

Join Our Literary Community

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive book recommendations, author interviews, and upcoming releases.

Comments on "Birds, Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 1, No. 3" :