The Project Gutenberg eBook of Genera and Subgenera of Chipmunks

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Genera and Subgenera of Chipmunks

Author: John A. White

Release date: November 23, 2009 [eBook #30533]

Most recently updated: December 15, 2010

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper, Anne Storer and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GENERA AND SUBGENERA OF CHIPMUNKS ***

Genera and Subgenera of Chipmunks

BY

JOHN A. WHITE

University of Kansas Publications

Museum of Natural History

Volume 5, No. 32, pp. 543-561, 12 figures in text

December 1, 1953

University of Kansas

LAWRENCE

1953

University of Kansas Publications,

Museum of Natural History

Editors: E. Raymond Hall, Chairman, A. Byron Leonard,

and Robert W. Wilson

Volume 5, No. 32, pp. 543-561, 12 figures in text

December 1, 1953

University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas

printed by

ferd voiland, jr., state printer

topeka, kansas

1953

[Pg 545]

Genera and Subgenera of Chipmunks

By

JOHN A. WHITE

Contents

| page | |

| Introduction | 546 |

| Historical | 546 |

| Methods, Materials, and Acknowledgments | 547 |

| Evaluation of Characters | 548 |

| Characters in which the Subgenera Eutamias | |

| and Neotamias Agree, but Differ from the | |

| Genus Tamias | 548 |

| Structure of the Malleus | 548 |

| Structure of the Baculum | 549 |

| Structure of the Hyoid Apparatus | 552 |

| Presence or Absence of P3 | 553 |

| Length of Tail in Relation to Total Length | 553 |

| Color Pattern | 554 |

| Characters in which the Subgenus Eutamias | |

| and the Genus Tamias Agree, but Differ | |

| from the Subgenus Neotamias | 554 |

| Shape of the Infraorbital Foramen | 554 |

| Width of the Postorbital Process at Base | 554 |

| Position of the Supraorbital Notch | 554 |

| Degree of Convergence of the Upper Tooth-rows | 554 |

| Degree of Constriction of the Interorbital Region | 555 |

| Shape of the Pinna | 555 |

| Structural Features that are too Weakly | |

| Expressed to be of Taxonomic Use | 555 |

| Discussion | 555 |

| Genera and Subgenera | 557 |

| Genus Eutamias Trouessart | 557 |

| Subgenus Eutamias Trouessart | 558 |

| Subgenus Neotamias Howell | 558 |

| Genus Tamias Illiger | 559 |

| Discussion | 559 |

| Conclusions | 560 |

| Literature Cited | 561 |

| ILLUSTRATIONS | |

|---|---|

| Figs. 1-3. Dorsomedial Views of Malleus | 549 |

| Figs. 4-10. Lateral Views of Baculum | 551 |

| Figs. 11-12. Ventral Views of Hyoid Apparatus | 552 |

[Pg 546]

Introduction

The supraspecific categories of the chipmunks, as in most other

groups of squirrels, have been a source of controversy for many

years. Before presenting new evidence and a review of older evidence

bearing on the problem, it seems desirable to review briefly

in chronological order, the taxonomic history of the genera and subgenera

of the chipmunks.

Historical

Linnaeus (1758:64) described the eastern North American chipmunks

under the name Sciurus striatus and based his description

on that of Catesby (1743:75). The Asiatic chipmunk was first described,

under the name Sciurus sibiricus, by Laxmann (1769:69).

Schreber (1785, 4:790) separated the Asiatic and North American

chipmunks into the Asiatic and American varieties. Gmelin

(1788:50) followed Schreber and, employing trinomials, used the

names Sciurus striatus asiaticus and S. s. americanus. Illiger

(1811:83) proposed Tamias as the generic name of the chipmunk

of eastern North America. Say (1823:45) described Sciurus quadrivittatus,

the first species of chipmunk known from western North

America.

Trouessart (1880:86-87) proposed Eutamias as the subgeneric

name to include the western North American and Asiatic chipmunks.

Merriam (1897:189-190) raised Eutamias to full generic rank.

In so doing he neither listed nor described any characters but wrote

that “it will be observed that the name Eutamias, proposed by

Trouessart in 1880 as a subgenus of Tamias is here adopted as a

full genus. This is because of the conviction that the superficial

resemblance between the two groups is accidental parallelism, in

no way indicative of affinity. In fact the two groups, if my notion

of their relationship is correct, had different ancestors, Tamias

being an offshoot of the ground-squirrels of the subgenus Ictidomys

of Allen, and Eutamias of the subgenus Ammospermophilus,

Merriam.”

Howell (1929:23) proposed Neotamias as the subgeneric name

for the chipmunks of western North America, of the genus Eutamias.

Ellerman (1940, 1:426) gave Eutamias and Neotamias equal

subgeneric rank with Tamias under the genus Tamias; on pages

427-428 he quoted Merriam, as I have done above, and later, after

quoting the key to the genera and subgenera of chipmunks of

Howell (1929:11), Ellerman wrote (op. cit.: 428-429), “This key

[Pg 547]convinces me that all these forms must be referred to one genus

only. The characters given to separate ‘Eutamias’ from Tamias are

based only on the absence or presence of the functionless premolar,

and on the colour pattern. If colour pattern is to be used as a

generic character, it seems Citellus suslicus will require a new name

when compared with C. citellus, etc.” And again, “The Asiatic

chipmunk is intermediate between typical Tamias and the small

American forms in many characters.” To substantiate this, Ellerman

(loc. cit.) quotes Howell (loc. cit.), in comparing the subgenera

Eutamias and Neotamias, as follows: “‘the ears [of subgenus

Eutamias] are broad, rounded, of medium height, much as in

Tamias; postorbital broad at base, tapering to a point, much as in

Tamias; interorbital constriction slight, as in Tamias; upper molariform

tooth rows slightly convergent posteriorly, as in Tamias.’”

Ellerman (loc. cit.) again quotes Howell (loc. cit.),

“‘Eutamias of

Asia resembles Tamias of North America and differs from American

Eutamias in a number of characters, notably the shape of the

anteorbital

foramen, the postorbital process, the breadth of the interorbital

region, the development of the lambdoidal crest, and the

shape of the external ears. On the other hand, American Eutamias

agrees with the Asiatic members of the genus in the shape of the

rostrum, the well-defined striations of the upper incisors, the presence

of the extra peg-like premolar, and in the pattern of the dorsal

stripes.’”

Bryant (1945:372) wrote, “I am convinced that Ellerman’s interpretation

of the relationships of the chipmunks is correct.” After

commenting that the presence or absence of P3, “is of significance

only in distinguishing between species of squirrels,” Bryant adds

that “The other differences between the eastern and the western

chipmunks do not appear to be of sufficient phylogenetic importance

to warrant the retention of the two groups as genera.”

Methods, Materials, and Acknowledgments

Characters previously mentioned in the literature as having taxonomic worth

for supraspecific categories of chipmunks were checked by me on specimens

old enough to have worn permanent premolars. Some structural features not

previously used were found to have taxonomic significance. The baculum in

each of the supraspecific categories of sciurids of North America was examined;

the bacula were processed by the method described by White (1951:125) to

obviate “variation” caused by shriveling of the smaller bacula or breaking of

the more delicate parts of the larger bacula. Mallei and hyoid bones of the

genera and subgenera of the chipmunks were mostly studied in the dry state.

[Pg 548]Part of the hyoid musculature in these same groups of chipmunks was dissected.

In all, I studied more than 1,000 skulls and skins of the subgenus Neotamias,

approximately 50 skulls and skins of Tamias striatus, and 15 skulls and skins

of the subgenus Eutamias (Eutamias sibiricus asiaticus from Manchuria).

Numerous other specimens were examined but not in such detail.

I am grateful to Professor E. Raymond Hall for guidance in the study. For

encouragement and advice I am grateful also to Doctors Robert W. Wilson,

Cecil G. Lalicker, Edwin C. Galbreath, Keith R. Kelson, E. Lendell Cockrum,

Olin L. Webb, and others at the Museum of Natural History, and in the

Department of Zoology of the University of Kansas. My wife, Alice M. White,

made the drawings and helped me in many other ways. For lending specimens

I thank Dr. David H. Johnson of the United States National Museum, and Dr.

George C. Rinker of the Department of Anatomy, University of Michigan.

Assistance with field work is acknowledged from the Kansas University

Endowment Association, the National Science Foundation, and the United

States Navy, Office of Naval Research, through contract No. NR161 791.

Evaluation of Characters

The following paragraphs treat the characters listed by Howell,

Ellerman, and Bryant, and such additional characters as I have

found useful in characterizing the genera and subgenera of chipmunks.

Some of the findings, I think, illustrate how study of such

mammalian structures as the baculum, malleus, and hyoid apparatus—structures

that seem to be little influenced by the changing external

environment—clarifies relationships, if these previously were

estimated only from other parts of the anatomy of Recent specimens.

The structural features and characters to be discussed, or listed,

below may be arranged in three categories as follows: 1) Characters

in which the subgenera Eutamias and Neotamias agree but

are different from the genus Tamias; 2) Characters in which the

subgenus Eutamias and the genus Tamias agree but are different

from the subgenus Neotamias; 3) Structural features that are too

weakly expressed to be of taxonomic use.

Characters in which the Subgenera Eutamias and Neotamias

Agree, but Differ from the Genus Tamias

Structure of the Malleus.—The malleus in chipmunks is composed

of a head and neck, a manubrium which has a spatulate process at

the end opposite the head, and a muscular process situated about

halfway between the spatulate process and the head of the malleus.

An articular facet begins on the manubrium near the neck and

spirals halfway around the head of the malleus. A lamina extends

from the anterior edge of the head and neck, tapers to a point and

joins the tympanic bulla anteriorly where there is a suture between

[Pg 549]

the lamina and bulla. The lamina is one half as long as the rest of

the malleus (see figs. 1-3).

The head of the malleus in Tamias is clearly more elongated than

in Eutamias. The plane formed by the lamina in Eutamias makes

an angle of approximately 90 degrees with the plane formed by the

manubrium; in Tamias the two planes make an angle of approximately

60 degrees.

Examination of series of mallei of Eutamias and Tamias indicate

that there is slight individual variation, slight variation with age,

and no secondary sexual variation. Intraspecific variation in the

subgenus Neotamias is slight, consisting of differences in size.

Specimens of the subgenus Eutamias from Manchuria have mallei

which are morphologically close to the mallei of the subgenus

Neotamias.

Figs. 1-3. Dorsomedial views of left malleus.

Fig. 1. Tamias striatus lysteri, No. 11920 sex?;

from Carroll Co., New Hampshire.

Fig. 2. Eutamias sibiricus asiaticus, No. 199637 male NM;

from I-mien-po, N. Kirin, Manchuria.

Fig. 3. Eutamias townsendii senex, No. 165 male;

from Lake Tahoe, California.

Structure of the Baculum.—In discussing the baculum in Eutamias

and Tamias, it seems desirable to do so in the light of the structure

of the baculum in other sciurids.

The bacula of North American sciurids are divisible into six distinct

types represented by those of the genera Spermophilus, Marmota,

Sciurus, Tamiasciurus, Eutamias, and Glaucomys.

The type of baculum in Spermophilus is spoonshaped with a

ventral process that is spinelike or keellike. Also, spines usually are

present along the margin of the “spoon.” The base (proximal end)

of the baculum is broad, and some species have a winglike process

extending dorsally and partly covering a longitudinal groove. The

[Pg 550]

shaft is more or less curved downward in the middle

(see figs. 7, 10).

In Marmota the baculum is greatly enlarged at the posterior end

and forms a shieldlike surface. The ventral surface of the base is

flattened and the ventral surface of the shaft curves slightly ventrally

then dorsally to the tip. The dorsal region of the base culminates

in a point, from which there is a ridge that extends anteriorly and

that tapers rapidly into the shaft near the tip. The tip, dorsally,

has a slight depression surrounded by knobs, which are more or

less well defined, and which resemble, topographically, the spines

described for Spermophilus (see fig. 8).

In Sciurus the baculum is semispoonshaped and asymmetrical.

There is a winglike process on one side and a spine, which projects

lateroventrally, on the other side of the tip. The base of the

baculum is broad but not so broad as in most species of Spermophilus.

Extending posteriorly from the region of the tip, at which

point a spine projects lateroventrally, there is a ridge, which is often

partly ossified and that extends to a point near the base (see fig. 4).

In Tamiasciurus the baculum is absent or vestigial (Layne,

1952:457-459).

In Eutamias the baculum is broad at the base and the shaft tapers

distally to the junction of the shaft and tip, or the base is only

slightly wider than any part of the shaft. The tip often forms an

abrupt angle with the shaft and there is a keel on the dorsal surface

of the tip (see figs. 5, 6).

The baculum in Glaucomys is the most distinctive of that of any

American sciurid. According to Pocock (1923:243-244), “The

baculum [of G. volans] is exceedingly long and slender, slightly

sinuous in its proximal third, and inclined slightly upwards distally.

The extreme apex is bifid, the lower process being rounded, the

upper more pointed. On the left side there is a long crest running

from the summit of the upper terminal process and ending abruptly

behind the left side about one-third of the distance from the proximal

end of the bone. It lies over a well-marked groove, and there

is a second shallower groove on the right side of the bone.” The

baculum of G. sabrinus is markedly wider, more flattened and

shorter than in G. volans. The crest, which is also present in

G. volans, starts from the upper terminal process and extends to

the base of the baculum on the left side. There is a knoblike process on

the crest at a point three fourths the length of the baculum from its

base. The distal one third of the baculum curves sharply but

smoothly upwards (see fig. 9).

[Pg 551]

Keeping in mind that the baculum in the North American sciurids

can be classified into six structural groups, as given above, the

baculum in each of the subgenera Eutamias and Neotamias and in

the genus Tamias is briefly described.

In the subgenus Neotamias the baculum resembles a leg and foot

of man, with a narrow ridge (keel) in the center of the “instep” of

the foot (Howell 1929:27). The tip (=foot) curves dorsally at

the distal end (see figs. 5, 6).

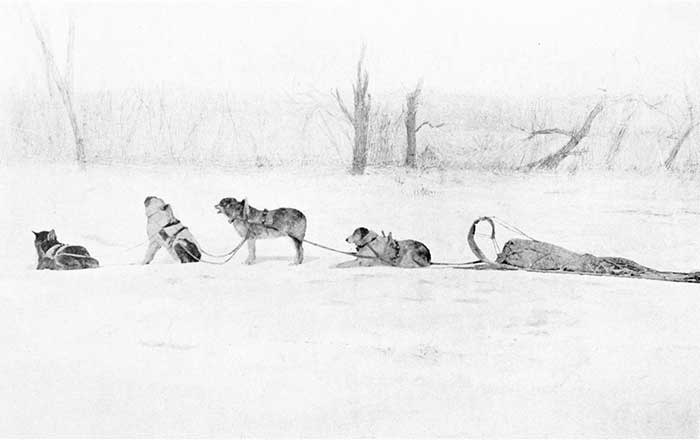

Figs. 4-10. Lateral views of right side

(except left-lateral view in fig. 9) of baculum.

Fig. 4. Sciurus aureogaster aureogaster,

No. 37000; from 70 km. S C. Victoria (by highway), and 6 km. W of

highway, Tamaulipas.

Fig. 5. Eutamias quadrimaculatus, No. 95780 BS;

from Mountains near Quincy, Plumas Co., California.

Fig. 6. Eutamias sibiricus asiaticus, No. 199632 NM;

from 120 mi. up the Yalu River, Korea.

Fig. 7. Tamias striatus lysteri, No. 193493 NM;

from Locust Grove, New York.

Fig. 8. Marmota flaviventer dacota, No. 41641;

from 1½ mi. E Buckhorn, 6,150 ft., Weston Co., Wyoming.

Fig. 9. Glaucomys sabrinus bangsi, No. 15079;

from 10 mi. NE Pinedale, 8,000 ft., Sublette Co., Wyoming.

Fig. 10. Spermophilus armatus, No. 14888;

from W end Half Moon Lake, 7,900 ft., Sublette Co., Wyoming.

In the subgenus Eutamias, the baculum “tapers gradually from

base to tip, the distal portion upturned in an even curve and slightly

[Pg 552]

flattened ...” (op. cit.:26). Microscopic examination reveals

that there is a faint keel on the dorsal surface of the tip.

Eutamias, like Callosciurus, Menetes,

Dremomys, Lariscus, Rhinosciurus,

and Nannosciurus, has a keel on the dorsal surface of the

tip of the baculum (compare figures 5 and 6 with the descriptions

and figures in Pocock, 1923:217-225).

In Tamias the baculum is “a slender bone 4.5-5 millimeters in

length, nearly straight, upturned at the tip and slightly expanded

into the shape of a narrow spoon or scoop, with a slight median

ridge on the under surface.” (Howell op. cit.:13.) The “median

ridge” is a keel on the ventral surface. In having a keel on the

ventral surface of the tip, the baculum of Tamias is comparable to

that of Spermophilus.

Examination of series of bacula of the subgenus Neotamias and

the genus Tamias indicates, as in the case of the mallei, that there

is slight individual variation and slight variation with age. In the

subgenus Neotamias interspecific variation in the baculum is

considerable, but the general plan of structure remains constant. From

this study of variation of the baculum in American chipmunks, it

can be extrapolated that the baculum in the Asiatic Eutamias would

show little individual variation in structure. I have seen only two

bacula of the Asiatic Eutamias.

Figs. 11-12. Ventral views of the hyoid apparatus in

Tamias and Eutamias.

Fig. 11. Tamias striatus venustus, No. 11072 female;

from Winslow, Washington Co., Arkansas.

Fig. 12. Eutamias minimus operarius, No. 5376 male;

from 14 mi. N El Rito, Rio Arriba Co., New Mexico.

Structure of the Hyoid Apparatus.—The hyoid apparatus in the

chipmunks is made up of an arched basihyal with a thyrohyal attached

to each limb of this “arch.” To each junction between the

“arch” and the thyrohyals, a hypohyal is attached by ligaments to a

flat articular surface. A ceratohyal then is attached posteriorly to

the hypohyal and a stylohyal ligament is attached to each ceratohyal

[Pg 553]

posteriorly. The stylohyal is loosely attached along its sides to the

tympanic bulla and finally attached, at the posterior end, to the

bulla at a point slightly ventral and posterior to the auditory meatus.

In the genus Eutamias the hypohyal and ceratohyal are completely

fused in adults, the suture between these two bones being visible

in juvenal specimens (see fig. 12).

In the genus Tamias the hypohyal and ceratohyal remain distinct

throughout life. The hypohyal may frequently be divided into two

parts, a variation which is also present in Marmota.

The musculature associated with the hyoid apparatus in Eutamias

and Tamias is as described by Bryant (1945:310, 316) for the Nearctic

squirrels. However, the conjoining tendon of the anterior and

posterior pairs of digastric muscles is ribbonlike in Eutamias and

rodlike (rounded in cross section) in Tamias.

The presence or absence of P3 and the projection of the anterior

root of P4 in relation to the masseteric knob.—Only rarely is P3

absent in Eutamias or present in Tamias. P3 in specimens of old

adult Eutamias, shows wear, thus suggesting that P3 is functional

in older chipmunks. In Eutamias, which normally has a P3, the

anterior root of P4 projects to the outside of the masseteric knob,

whereas in Tamias, which normally lacks a P3, the anterior root of

P4 projects directly to the masseteric knob or to the lingual side of

this structure. The projection of the anterior root of P4 seems to

be correlated with the presence or absence of P3. However, in a

specimen of Tamias striatus rufescens (No. 11117 KU), the left P3

is present, yet the anterior root of P4 still projects to the lingual

side of the masseteric knob.

Ellerman (1940:48) and Bryant (1945:368-369, 372) think that

the presence or absence of P3 is not of generic significance in chipmunks,

since P3 is vestigial and probably is in the process of being

lost, and since this character is rarely used as a generic character

in other sciurids. I think that the presence or absence of P3, together

with the projection of the anterior root of P4 in relation to

the masseteric knob, is of generic significance, for, squirrels in general

have retained the dentition and dental formula of a primitive

rodent, and any change in the pattern of the teeth or in dental

formula is, in my opinion, of a fundamental nature.

Length of tail in relation to total length.—The tail in Eutamias

is more than 40 per cent of the total length, whereas in Tamias the

tail is less than 38 per cent of the total length. In this respect

Tamias resembles most ground squirrels of the genus Spermophilus.

[Pg 554]

Color pattern.—The chipmunks vary but little in color pattern,

for, even in Eutamias dorsalis, which is one of the most aberrant

of the chipmunks in color pattern, the pattern is characteristic of

Eutamias.

The width of the longitudinal stripes is uniform in Eutamias

whereas in Tamias the dorsal, longitudinal light stripes are more

than twice as wide as the other stripes.

In Eutamias, only the two lateralmost dark stripes are short,

whereas in Tamias all four of the lateral dark stripes are short; none

extends to the rump or to the shoulder.

The dark median stripe is present in both Eutamias and Tamias

as well as in other genera such as Callosciurus and Menetes (Ellerman

1940:390).

Characters in which the Subgenus Eutamias and the Genus

Tamias Agree,

but Differ from the Subgenus Neotamias

Shape of the infraorbital foramen.—In the subgenus Eutamias

and in the genus Tamias the infraorbital foramen is rounded,

whereas in most species of the subgenus Neotamias the foramen is

slitlike. In Eutamias townsendii, however, the infraorbital foramen

is rounded as much as in the subgenus Eutamias and in the genus

Tamias.

Width of the postorbital process at base.—The postorbital process

is broader at the base in the subgenus Eutamias and in the genus

Tamias than in most species of the subgenus Neotamias. In E.

townsendii, however, this process is relatively as broad as in the

subgenus Eutamias and in the genus Tamias.

Position of the supraorbital notch in relation to the posterior notch

of the zygomatic plate.—In the subgenus Eutamias and in the genus

Tamias the supraorbital notch is distinctly anterior to the posterior

notch of the zygomatic plate, whereas in the subgenus Neotamias,

the supraorbital notch is only slightly anterior to the posterior notch

of the zygomatic plate. This difference may be correlated with

differences in size, since specimens of the subgenus Eutamias and

the genus Tamias are larger than specimens of the subgenus

Neotamias.

Degree of convergence of the upper tooth-rows.—The rows of

upper cheek-teeth converge posteriorly in the subgenus Eutamias

and in the genus Tamias, except that in some specimens of E.

sibiricus asiaticus the rows of upper cheek-teeth are nearly parallel

to each other. In most species of the subgenus Neotamias the rows

[Pg 555]of upper cheek-teeth are nearly parallel to each other, although in

the specimens that I have seen of E. townsendii, the upper rows of

cheek-teeth converge posteriorly.

Degree of constriction of the interorbital region.—The interorbital

region is more constricted in most species of the subgenus Neotamias

than in the subgenus Eutamias and the genus Tamias. In

specimens of E. t. townsendii of the subgenus Neotamias, however,

the degree of constriction of the interorbital region is approximately

the same as in the subgenus Eutamias and the genus Tamias.

Shape of the pinna.—The pinna is narrower and more pointed in

the subgenus Neotamias than in the subgenus Eutamias and the

genus Tamias.

Structural Features that are too Weakly Expressed to be of

Taxonomic Use

The following alleged characters have been mentioned in the

literature. Since the degree of expression of these features is so

slight, or since there is marked variation within one or more natural

groups of chipmunks, no reliance is here placed on these features.

They are as follows: (1) Degree of the posterior projection of the

palate; (2) relative size of the auditory bullae; (3) position, in

relation to P4, of the notch in the posterior edge of the zygomatic

plate; (4) size of m3 in relation to m2; (5) degree of development

of the mesoconid and ectolophid of the lower molars; (6) shape

and length of the rostrum; (7) degree of distinctness of minute

longitudinal grooves on the upper incisors.

A variation that does not readily fall in any one of the three categories

mentioned above is the degree of development of the lambdoidal

crest. The crest is least developed in the subgenus Neotamias

and most developed in the genus Tamias. The larger the

skull, the more the lambdoidal crest is developed; seemingly, therefore,

the degree of development is an expression of size of the skull

and may be determined by heterogonic growth.

Discussion

As shown in table 1, there are ten characters by means of which

Eutamias and Tamias can be separated consistently. The subgenus

Eutamias occurs on the Asiatic side and the subgenus Neotamias

occurs on the North American side of Bering Strait, yet the two

subgenera agree in the ten features referred to. Although the subgenus

Neotamias and the genus Tamias occur together in parts of

the United States and Canada, they differ in the ten features, indicating

[Pg 556]that the subgenera Eutamias and Neotamias are more

closely related to each other than either is to Tamias.

Table 1.—Characters by Means of Which the Genera Eutamias and

Tamias Can Be Distinguished

| Character | Eutamias | Tamias |

| Shape of head of malleus. | not elongated. | elongated. |

| Angle formed by planes of lamina and manubrium of malleus. | approximately 90 degrees. | approximately 60 degrees. |

| Position of keel on tip of baculum. | dorsal. | ventral. |

| Relation of hypohyal and ceratohyal bones of hyoid apparatus. | fused in adults. | never fused. |

| Appearance in cross section of conjoining tendon of anterior and posterior digastric muscles. | flattened. | rounded. |

| Presence or absence of P3. | present. | absent. |

| Projection of anterior root of P4 in relation to masseteric knob. | buccal. | lingual. |

| Length of tail in relation to total length. | more than 40 per cent. | less than 38 per cent. |

| Width of longitudinal stripes. | subequal. | median pair of light stripes twice as wide as others. |

| Length of lateral longitudinal light stripes. | outermost pair short. | both pairs short. |

It must be pointed out here that the subgenus Neotamias always

differs from both the subgenus Eutamias and the genus Tamias in

pointed versus rounded pinna of ear (see table 2) and in the

supraorbital notch being slightly posterior to or even with, instead of

distinctly anterior to, the posterior notch of the zygomatic plate.

The relative position of these two notches, however, seems to be a

matter of relative (heterogonic) growth. Further, the base of the

postorbital process of the frontal usually is narrower (relative to

the length of the process) in the subgenus Neotamias but there is

[Pg 557]

a gradation in this feature in Neotamias culminating in the species

E. townsendii in which the bases of the processes are relatively as

broad as in the subgenus Eutamias and the genus Tamias. The

same condition obtains in the shape of the infraorbital foramen

which is subovate to rounded in the subgenus Neotamias and always

rounded in the other chipmunks.

Table 2.—Characters by Means of Which the Subgenus Eutamias and the

Genus Tamias May Be Distinguished from the Subgenus Neotamias

| Character | subgenus Neotamias | subgenus Eutamias | genus Tamias |

| Shape of infraorbital foramen. | subovate to rounded. | always rounded. | always rounded. |

| Relative width of the postorbital process at base. | narrow to broad. | broad. | broad. |

| Position of supraorbital notch in relation to posterior notch of zygomatic plate. | even with or slightly posterior. | anterior. | anterior. |

| Convergence, posteriorly, of upper tooth-rows. | not always. | not always. | always. |

| Degree of constriction of interorbital region. | slight to marked. | marked. | marked. |

| Shape of pinna. | long and pointed. | broad and rounded. | broad and rounded. |

These differences of Neotamias are so slight in comparison with

the similarities (ten features mentioned above) that Neotamias

here is accorded only subgeneric rank under the genus Eutamias,

instead of generic rank.

Howell’s (1929) arrangement of the genera and subgenera of

chipmunks is judged to be correct as indicated by the following

arrangement that I propose.

Genera and Subgenera

Genus Eutamias Trouessart

Eutamias Trouessart, E. L. Catal. Mamm. viv. et foss., Rodentia,

in Bull. Soc. d’Etudes Sci. d’Angers, 10:86-87, 1880. Type

Sciurus striatus asiaticus Gmelin.

Eutamias, Merriam, C. H., Proc. Biol. Soc. Washington,

11:189-190, July 1, 1897.

[Pg 558]

Eutamias, Howell, A. H., N. Amer. Fauna, 52:26, November 30, 1929.

Tamias, Ellerman, J. R., The families and genera of living rodents.

British Mus. (Nat. Hist.), 1:426, June 8, 1940.

Tamias, Bryant, M. D., Amer. Midland Nat., 33:732, March 1945.

Diagnosis.—Skull lightly built, narrow; postorbital process

light and weak; lacrimal not elongated; infraorbital foramen lacks canal,

relatively larger than in most sciurids; P3 present; head of malleus

not elongated; plane of manubrium of malleus 90 degrees to plane of

lamina; hypohyal and ceratohyal bones of hyoid apparatus fused in adults;

conjoining tendon between anterior and posterior sets of digastric

muscles ribbonlike; keel on dorsal side of tip of baculum; tail more than

40 per cent of total length; five longitudinal dark stripes evenly

spaced and subequal in width; two lateral dark stripes short.

Subgenus Eutamias Trouessart

Eutamias Trouessart, E. L. Catal. Mamm. viv. et foss., Rodentia, in Bull.

Soc. d’Etudes Sci. d’Angers 10:86-87, 1880. Type Sciurus striatus

asiaticus Gmelin.

Eutamias, Howell, A. H., N. Amer. Fauna, 52:26, November 30, 1929.

Eutamias, Ellerman, J. R., The families and genera of living rodents. British

Mus. (Nat. Hist.), 1:426, June 8, 1940.

Eutamias, Bryant, M. D., Amer. Midland Nat. 33:732, March 1945.

Diagnosis.—Size large; lambdoidal crest moderately developed; supraorbital

notches distinctly anterior to posterior notch of zygomatic plate; baculum with

faint keel on dorsal surface of tip which curves upward; pelage coarse; ears

broad, rounded, of medium height.

Geographic range.—Palearctic. West to Dvina and Kama rivers, Vologda,

and Kazan, in European Russia. South to southern Ural Mountains, Altai

Mountains; Kansu, Szechwan, Shensi, Shansi, and Chihli provinces of China;

Manchuria and Korea. East to Hokkaido Island, Japan; Kunashiri Island,

southern Kurile Islands; Sakhalin Island, and Yakutsk, Siberia. North nearly

to Arctic Coast in Siberia and European Russia (Ellerman and Morrison-Scott

1951:503).

Subgenus Neotamias Howell

Neotamias Howell, A. H., N. Amer. Fauna, 52:26, November 30, 1929.

Type, Eutamias merriami J. A. Allen [=Tamias asiaticus merriami J. A.

Allen].

Neotamias, Ellerman, J. R., The families and genera of living rodents. British

Mus. (Nat. Hist.), 1:426, June 8, 1940.

Neotamias, Bryant, M. D., Amer. Midland Nat., 33:372, March, 1945.

Diagnosis.—Size small to medium; lambdoidal crest barely discernible;

supraorbital notches even with, or posterior to, posterior notch of zygomatic

plate; baculum with distinct keel on dorsal surface of tip which curves upward;

pelage silky; ears long and pointed.

Geographic range.—Western Nearctic. West to Pacific Coast. South to

Lat. 20°30' in Baja California and to northwestern Durango and southeastern

Coahuila, Mexico. East to eastern New Mexico, westernmost Oklahoma, eastern

Colorado, Wyoming, northwestern Nebraska, western and northwestern South

Dakota, western and northwestern North Dakota, northeastern Minnesota,

northern Wisconsin and Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and eastern Ontario.

[Pg 559]

North to southwestern shore of Hudson Bay, southern shore of Great Slave

Lake and Yukon River, Yukon.

Genus Tamias Illiger

Tamias Illiger, J. K. W., Prodromus Syst. Mam. Avium, pp. 83, 1811. Type,

Sciurus striatus Linnaeus.

Tamias, Howell, A. H., N. Amer. Fauna, 52:26, November 30, 1929.

Tamias, Ellerman, J. R., The families and genera of living rodents. British

Mus. (Nat. Hist.), 1:426, June 8, 1940.

Tamias, Bryant, M. D., Amer. Midland Nat. 33:372, March, 1945.

Diagnosis.—Skull lightly built, narrow; postorbital process small and weak;

lacrimal not elongated; infraorbital foramen lacks canal, relatively larger than

in most sciurids; P3 absent; head of malleus elongated; plane of manubrium

of malleus forms 60 degree angle with plane of lamina; hypohyal and ceratohyal

bones of hyoid apparatus fused in adults; conjoining tendon of anterior and

posterior digastric muscles rounded in cross section; keel on ventral surface of

tip which curves upward in baculum; tail less than 38 per cent of total length;

five longitudinal dark and four longitudinal light stripes present but two dorsal

light stripes at least twice as broad as other stripes; four lateral dark stripes

short.

Geographic range.—Eastern Nearctic. West to Turtle Mountains, North

Dakota; eastern North Dakota, eastern South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and

Oklahoma. South to southern Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, northwestern

Georgia. East to Atlantic Coast from South Carolina to Nova Scotia. North

to northeastern Quebec and southern tip of Hudson Bay.

Discussion

Chipmunks are small striped squirrels that inhabit the Holarctic

Realm and that are found in similar niches in each of the three

regions: Palearctic, western Nearctic, and eastern Nearctic. Ellerman

(1940) and Bryant (1945) placed the chipmunks in three

subgenera, corresponding to the regions mentioned above, under

the one genus Tamias. Critical examination of new and old evidence

reveals, nevertheless, that the subgenera Eutamias and

Neotamias of the genus Eutamias are more closely related to one

another than either is to the genus Tamias. This relationship can

be seen clearly in the structure of the malleus, baculum, hyoid apparatus,

hyoid musculature, the presence or absence of P3, the

projection of the anterior root of P4 in relation to the masseteric

knob, and in the color pattern.

Because the genera Eutamias and Tamias occupy similar ecological

niches, the structural similarities that permit these animals to

be called chipmunks, show convergence, and thus can be assumed

to be adaptive. These similarities are in the molars, in shape of the

skull, in color pattern and in other features which have been used

[Pg 560]

by many systematists to interpret the phylogenetic relationships of

the squirrels. Pocock (1923:211), however, reviewed the taxonomic

literature on sciurids and wrote: “The conclusion very forcibly

suggested by the literature of the subject is the untrustworthiness

of such characters.” Pocock (op. cit.), correctly in my opinion,

then established a supraspecific classification of the sciurids based

almost exclusively on the structure of the baculum and glans penis.

I have studied the baculum in chipmunks and in all the major

supraspecific groups of Nearctic squirrels. The bacula of the

Nearctic squirrels and those of the Palearctic and Indian squirrels,

other than the chipmunks, are described and figured by Pocock (op.

cit.).

The baculum in Eutamias, in general plan of structure, resembles

the baculum in the genera Callosciurus, Menetes, Rhinosciurus,

Lariscus, Dremomys, and Nannosciurus, of the tribe Callosciurini

Simpson. The baculum in Tamias, in general plan of structure, resembles

that in Spermophilus (=Citellus) and Cynomys of the

tribe Marmotini Simpson. These tribes, designated by Simpson

(1945:79), are based on the corresponding subfamilies defined by

Pocock (1923:239-240) primarily on differences in the structure of

the baculum. I assign Tamias to the tribe Marmotini. I assign

Eutamias to the tribe Callosciurini, but do so only tentatively

because I have not, at first hand, studied the bacula of most of the

Callosciurini. The fossil record is too incomplete to reveal the time

when the two tribes diverged. The subgenera Eutamias and Neotamias

are closely related. Indications are that the divergence of

the two subgenera occurred, geologically, but a short time ago,

possibly in Pleistocene time.

Conclusions

1. Eutamias and Tamias are distinct genera of chipmunks.

2. The subgenera Eutamias and Neotamias are valid, for, Eutamias

sibiricus differs from all the species of the subgenus Neotamias

to a greater degree than these species differ from one another.

3. The genera Eutamias and Tamias probably evolved from two

distinct lines of sciurids; one line (Eutamias) is represented by the

tribe Callosciurini, and the other (Tamias) by the tribe Marmotini.

[Pg 561]

Literature Cited

Catesby, M.

1743. The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands,

etc., 2:i-xliv, 1-20, 1-100.

Ellerman, J. R.

1940. The families and genera of living rodents. British Mus. (Nat. Hist.),

Vol. 1, pp. xxvi + 689, 189 figs., June 8.

Ellerman, J. R., and T. C. S. Morrison-Scott.

1951. Checklist of Palearctic and Indian mammals. British Mus. (Nat.

Hist.), pp. 1-810, 1 map, November 30.

Gmelin, J. F.

1788. Systema Naturae. 1:1-500.

Howell, A. H.

1929. Revision of the American chipmunks (genera Tamias and Eutamias).

N. Amer. Fauna 52:1-157, 10 pls., 9 maps, November 30.

Illiger, J. K. W.

1811. Prodromus systematis mammalium et avium additis terminis zoographicis

utriuque classis, pp. xviii + 302, C. Salfeld.

Laxmann, M. E.

1769. Sibiriche Brief, pp. iv + 104, Gottingen and Gotha.

Layne, J. N.

1952. The os genitale of the red squirrel, Tamiasciurus. Jour. Mamm.

33:457-459, 1 fig., November 19.

Linnaeus, C.

1758. Systema Naturae. 1:1-824.

Merriam, C. H.

1897. Notes on the chipmunks of the genus Eutamias occurring west of the

east base of the Cascade-Sierra system, with descriptions of new

forms. Proc. Biol. Soc. Washington, 11:189-212, July 1.

Pocock, R. I.

1923. The classification of the Sciuridae. Proc. Zool. Soc. London, 1923:209-246,

June.

Say, T. (in Edwin James).

1823. Account of an expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains,

performed in the years 1819 and 1820, under the command of Major

Stephen H. Long. From the notes of Major Long, Mr. T. Say, and

other gentlemen of the exploring party. Compiled by Edwin James.

Vol. 1, pp. 1-503; Vol. 2, pp. 1-442 + appendix i-xcviii.

Schreber, J. C. D.

1785. Saugthiere, 4:790-802.

Simpson, G. G.

1945. The principles of classification and a classification of mammals. Bull.

Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist., 85:xvi + 350, October 5.

Trouessart, E. L.

1880. Catalogue des mammiferes vivants et fossiles. Ordre des Rongeurs.

Bull. Soc. d’Etudes Sci. d’Angers, 10:58-212.

White, J. A.

1951. A practical method for mounting the bacula of small mammals.

Jour. Mamm. 32:125, February 15.

Transmitted June 26, 1953.

Featured Books

Fox Trapping: A Book of Instruction Telling How to Trap, Snare, Poison and Shoot

A. R. Harding

oxSacking FoxesWire or Twine SnareThe Wire LoopSpring Pole SnareThe Runway Snare SetSome Canadian Re...

Noteworthy Mammals from Sinaloa, Mexico

Ticul Alvarez, J. Knox Jones, and M. Raymond Lee

in Sinaloa with the aim of acquiring materialssuitable for treating the entire mammalian fauna of t...

![Birds Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 3, No. 1 [January, 1898]](https://img.gamelinxhub.com/images/pg34165.cover.small.jpg)

Birds Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 3, No. 1 [January, 1898]

Various

des later works, and I will say that thepictures of birds given in your magazine are infinitely more...

Wild Bees, Wasps and Ants and Other Stinging Insects

Edward Saunders

n be recognized by any one who is disposed to make a special study of the group.The author has not ...

Some Reptiles and Amphibians from Korea

J. Knox Jones, Robert G. Webb, and George William Byers

Theodore H. Eaton, Jr. Volume 15, No. 2, pp. 149-173 ...

The Big Otter

R. M. Ballantyne

��And so we would go off together for the day.One morning Lumley said to me, “I’m off to North R...

A Book of Nonsense

Edward Lear

There was an Old Man on a hill, Who seldom, if ever, stood still; He r...

Industrial Revolution

Poul Anderson

o.""'Ware metaphor!" cried someone at my elbow. I turned and saw MissyBlades. She'd come quietly int...

Browse by Category

Join Our Literary Community

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive book recommendations, author interviews, and upcoming releases.

Comments on "Genera and Subgenera of Chipmunks" :