The Project Gutenberg eBook of House Rats and Mice

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: House Rats and Mice

Author: David E. Lantz

Release date: March 10, 2011 [eBook #35542]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Erica Pfister-Altschul, Larry B. Harrison and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HOUSE RATS AND MICE ***

HOUSE RATS AND MICE

DAVID E. LANTZ

Assistant Biologist

FARMERS’ BULLETIN 896

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

Contribution from the Bureau of Biological Survey

E. W. NELSON, Chief

Washington, D. C. October, 1917

Show this bulletin to a neighbor. Additional copies may be

obtained free from the Division of Publications, United States

Department of Agriculture

WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1917

The rat is the worst animal pest in the world.

From its home among filth it visits dwellings and

storerooms to pollute and destroy human food.

It carries bubonic plague and many other diseases

fatal to man and has been responsible for more untimely

deaths among human beings than all the wars

of history.

In the United States rats and mice each year destroy

crops and other property valued at over $200,000,000.

This destruction is equivalent to the gross earnings

of an army of over 200,000 men.

On many a farm, if the grain eaten and wasted by

rats and mice could be sold, the proceeds would more

than pay all the farmer's taxes.

The common brown rat breeds 6 to 10 times a

year and produces an average of 10 young at a litter.

Young females breed when only three or four months

old.

At this rate a pair of rats, breeding uninterruptedly

and without deaths, would at the end of three years

(18 generations) be increased to 359,709,482 individuals.

For centuries the world has been fighting rats

without organization and at the same time has been

feeding them and building for them fortresses for

concealment. If we are to fight them on equal terms

we must deny them food and hiding places. We must

organize and unite to rid communities of these pests.

The time to begin is now.

HOUSE RATS AND MICE.

CONTENTS.

- Page.

- Destructive habits

3 - Protection of food and other stores

5- Rat-proof building

5 - Keeping food from rats and mice

9

- Rat-proof building

- Destroying rats and mice

11- Traps

11 - Poisons

15 - Domestic animals

18 - Fumigation

18 - Rat viruses

19 - Natural enemies

20

- Traps

- Organized efforts to destroy rats

20- Community efforts

21 - State and national aid

21

- Community efforts

- Important repressive measures

23

DESTRUCTIVE HABITS OF HOUSE RATS AND MICE.

Losses from depredations of house rats amount to many millions

of dollars yearly—to more, in fact, than those from all other

injurious mammals combined. The common house mouse[1] and the

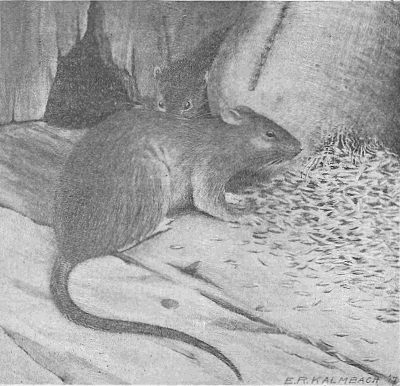

brown rat[2] (fig. 1), too familiar to need description, are pests in

nearly all parts of the country; while two other kinds of house rats,

known as the black rat[3] and the roof rat,[4] are found within our

borders.

Fig. 1.—Brown rat.

Of these four introduced species—for none is native to America—the

brown rat is the most destructive, and, except the mouse, the most

numerous and most widely distributed. Brought to America just[Pg 4]

before the Revolution, it has supplanted and nearly exterminated

its less robust relative the black rat; and in spite of the constant warfare

of man has extended its range and steadily increased in numbers.

Its dominance is due to its great fecundity and its ability to adapt

itself to all sorts of surroundings. It breeds (in the middle part of

the United States) six or more times a year and produces from 6 to

20 young (average 10) in a litter. Females breed when only 3 or 4

months old. Thus a pair, breeding uninterruptedly and without

deaths, could in three years (18 generations) produce a posterity of

359,709,480 individuals. Mice and the black and roof rats produce

smaller litters, but the period of gestation, about 21 days, and the

number of litters are the same for all.

Rats and mice are practically omnivorous, feeding upon all kinds

of animal and vegetable matter. The brown rat makes its home in

the open field, the hedge row, and the river bank, as well as in stone

walls, piers, and all kinds of buildings. It destroys grains when

newly planted, while growing, and in the shock, stack, mow, crib,

granary, mill, elevator, or ship's hold, and also in the bin and feed

trough. It invades store and warehouse and destroys furs, laces,

silks, carpets, leather goods, and groceries. It attacks fruits, vegetables,

and meats in the markets, and destroys by pollution ten times

as much as it actually eats. It destroys eggs and young poultry, and

eats the eggs and young of song and game birds. It carries disease

germs from house to house and bubonic plague from city to city.

It causes disastrous conflagrations; floods houses by gnawing lead

water pipes; ruins artificial ponds and embankments by burrowing;

and damages foundations, floors, doors, and furnishings of dwellings.

Unlike the brown rat the black rat rarely migrates to the fields.

It has disappeared from most parts of the Northern States, but is

occasionally found in remote villages or farms. At our seaports it

frequently arrives on ships from abroad, but seldom becomes very

numerous. The roof rat is common in many parts of the South,

where it is a persistent pest in cane and rice fields. It maintains

itself against the brown rat partly because of its habit of living in

trees. The common house mouse by no means confines its activities

to the inside of buildings, but is often found in open fields, where its

depredations in shock and stack are well known.

Not only are mice and rats, especially the brown rat, a cause of

destruction and damage to property, but they are also a constant

menace to the health of man. It has been proved that they are the

chief means of perpetuating and transmitting bubonic plague and

that they play important rôles in conveying other diseases to human

beings. They are parasites, without redeeming characteristics, and

should everywhere be routed and destroyed.

PROTECTION OF FOOD AND OTHER STORES FROM RATS AND MICE.

Past attempts to exterminate rats and mice have failed, not so much

because of lack of effective means as because of the neglect of necessary

precautions and the absence of concerted endeavors. We have

rendered our work abortive by continuing to provide subsistence and

hiding places for the animals. If these advantages are denied, persistent

and general use of the usual methods of destruction will prove

far more successful.

RAT-PROOF BUILDING.

First in importance, as a measure of rat repression, is the exclusion

of the animals from places where they find food and safe retreats for

rearing their young.

The best way to keep rats from buildings, whether in city or in

country, is to use cement in construction. As the advantages of this

material are coming to be generally understood, its use is rapidly extending

to all kinds of buildings. The processes of mixing and laying

this material require little skill or special knowledge, and

workmen of ordinary intelligence can successfully follow the plain

directions contained in handbooks of cement construction.[5]

Many modern public buildings are so constructed that rats can

find no lodgment in the walls or foundations, and yet in a few years,

through negligence, such buildings often become infested with the

pests. Sometimes drain pipes are left uncovered for hours at a time.

Often outer doors, especially those opening on alleys, are left ajar.

A common mistake is failure to screen basement windows which must

be opened for ventilation. However the intruders are admitted, when

once inside they intrench themselves behind furniture or stores, and

are difficult to dislodge. The addition of inner doors to vestibules is

an important precaution against rats. The lower edge of outer doors

to public buildings, especially markets, should be reinforced with

light metal plates to prevent the animals from gnawing through.

Any opening left around water, steam, or gas pipes, where they go

through walls, should be closed carefully with concrete to the full

depth of the wall.

Dwellings.—In constructing dwelling houses the additional cost of

making the foundations rat-proof is slight compared with the advantages.

The cellar walls should have concrete footings, and the

walls themselves should be laid in cement mortar. The cellar floor

should be of medium rather than lean concrete. Even old cellars

may be made rat-proof at comparatively small expense. Rat holes

may be permanently closed with a mixture of cement, sand, and

broken glass, or sharp bits of crockery or stone.

[Pg 6]

On a foundation like the one described above, the walls of a wooden

dwelling also may be made rat-proof. The space between the sheathing

and lath, to the height of about a foot, should be filled with concrete.

Rats can not then gain access to the walls, and can enter the

dwelling only through doors or windows. Screening all basement

and cellar windows with wire netting is a most necessary precaution.

Old buildings in cities.—Aside from old dwellings, the chief refuges

for rats in cities are sewers, wharves, stables, and outbuildings.

Modern sewers are used by the animals merely as highways and not as

abodes, but old-fashioned brick sewers often afford nesting crannies.

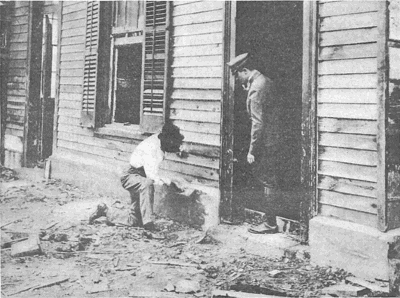

Fig. 2.—Rat-proofing a frame dwelling

by concrete side wall (United States Public Health Service, New Orleans,

La., 1914).

Wharves, stables, and outbuildings in cities should be so built as to

exclude rats. Cement is the chief means to this end. Old tumble-down

buildings and wharves should not be tolerated in any city.

(See fig. 2.)

In both city and country, wooden floors of sidewalks, areas, and

porches are commonly laid upon timbers resting on the ground.

Under such floors rats have a safe retreat from nearly all enemies.

The conditions can be remedied in towns by municipal action requiring

that these floors be replaced by others made of cement. Areas or

walks made of brick are often undermined by rats and may become

as objectionable as those of wood. Wooden floors of porches should

always be well above the ground.

[Pg 7]

Farm buildings.—Granaries, corncribs, and poultry houses may be

made rat-proof by a liberal use of cement in the foundations and

floors; or the floors may be of wood resting upon concrete. Objection

has been urged against concrete floors for horses, cattle, and poultry,

because the material is too good a conductor of heat, and the health

of the animals suffers from contact with these floors. In poultry

houses, dry soil or sand may be used as a covering for the cement

floor, and in stables a wooden floor resting on concrete is just as satisfactory

so far as the exclusion of rats is concerned.

The common practice of setting corncribs on posts with inverted

pans at the top often fails to exclude rats, because the posts are not

high enough to place the lower cracks of the structure beyond reach

of the animals. As rats are excellent jumpers, the posts should be

tall enough to prevent the animals from obtaining a foothold at any

place within 3 feet of the ground. A crib built in this way, however,

is not very satisfactory.

For a rat-proof crib a well-drained site should be chosen. The

outer walls, laid in cement, should be sunk about 20 inches into the

ground. The space within the walls should be grouted thoroughly

with cement and broken stone and finished with rich concrete for a

floor. Upon this the structure may be built. Even the walls of the

crib may be of concrete. Corn will not mold in contact with them,

provided there is good ventilation and the roof is water-tight.

However, there are cheaper ways of excluding rats from either

new or old corncribs. Rats, mice, and sparrows may be kept out

effectually by the use of either an inner or an outer covering of galvanized-wire

netting of half-inch mesh and heavy enough to resist

the teeth of the rats. The netting in common use in screening cellar

windows is suitable for covering or lining cribs. As rats can climb

the netting, the entire structure must be screened, or, if sparrows are

not to be excluded, the wire netting may be carried up about 3

feet from the ground, and above this a belt of sheet metal about a

foot in width may be tacked to the outside of the building.

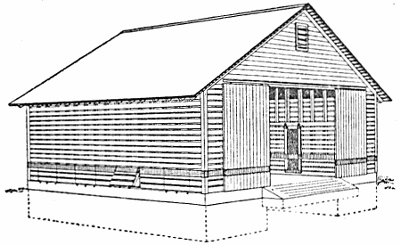

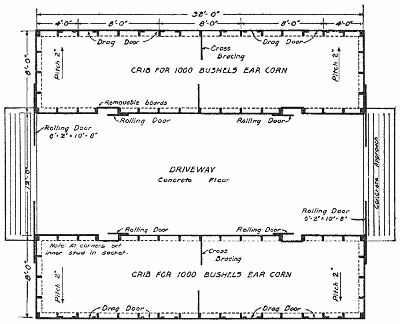

Complete working drawings for the practical rat-proof corncrib

shown in figures 3 and 4 may be obtained from the Office of Public

Roads and Rural Engineering of the department.

Buildings for storing foodstuffs.—Whenever possible, stores of food

for man or beast should be placed only in buildings of rat-proof

construction, guarded against rodents by having all windows near

the ground and all other possible means of entrance screened with

netting made of No. 18 or No. 20 wire and of ¼-inch mesh. Entrance

doors should fit closely, should have the lower edges protected by

wide strips of metal, and should have springs attached, to insure that

they shall not be left open. Before being used for housing stores,

the building should be inspected as to the manner in which water,

[Pg 8]

steam, or gas pipes go through the walls, and any openings found

around such pipes should be closed with concrete.

Fig. 3.—Perspective of rat-proof

corncrib, showing concrete foundation by dotted lines; also

belt of metal.

If rat-proof buildings are not available, it is possible, by the use

of concrete in basements and the other precautions just mentioned, to

make an ordinary building practically safe for food storage.

When it is necessary to erect temporary wooden structures to hold

forage, grain, or food supplies for army camps, the floors of such

buildings should not be in contact with the ground, but elevated, the

sills having a foot or more of clear space below them. Smooth posts

rising 2 or 3 feet above the ground may be used for foundations,

and the floor itself may be protected below by wire netting or sheet

metal at all places where rats could gain a foothold. Care should be

taken to have the floors as tight as possible, for it is chiefly scattered

grain and fragments of food about a camp that attract rats.

Rat-proofing by elevation.—The United States Public Health Service

reports that in its campaigns against bubonic plague in San

Francisco (1907) and New Orleans (1914) many plague rats were

found under the floors of wooden houses resting on the ground.

These buildings were made rat-proof by elevation, and no case of

either human or rodent plague occurred in any house after the

change. Placing them on smooth posts 18 inches above the ground,

with the space beneath the floor entirely open, left no hiding place

for rats.

This plan is adapted to small dwellings throughout the South, and

to small summer homes, temporary structures, and small farm buildings

everywhere. Wherever rats might obtain a foothold on the

top of the post they may be prevented from gnawing the adjacent

wood by tacking metal plates or pieces of wire netting to floor or sill.

KEEPING FOOD FROM RATS AND MICE.

The effect of an abundance of food on the breeding of rodents

should be kept in mind. Well-fed rats mature quickly, breed often,

and have large litters. Poorly fed rats, on the contrary, reproduce

less frequently and have smaller litters. In addition, scarcity of food

makes measures for destroying the animals far more effective.

Merchandise in stores.—In all parts of the country there is a serious

economic drain in the destruction by rats and mice of merchandise

held for sale by dealers. Not only foodstuffs and forage, but textiles,

clothing, and leather goods are often ruined. This loss is due mainly

to the faulty buildings in which the stores are kept. Often it would

be a measure of economy to tear down the old structures and replace

them by new ones. However, even the old buildings may often be

repaired so as to make them practically rat-proof; and foodstuffs, as

flour, seeds, and meats, may always be protected in wire cages at

slight expense. The public should be protected from insanitary

stores by a system of rigid inspection.

Fig. 4.—Floor

plan of rat-proof corncrib shown in figure 3.

Household supplies.—Similar care should be exercised in the home to

protect household supplies from mice and rats. Little progress in

ridding the premises of these animals can be made so long as they

have access to supplies of food. Cellars, kitchens, and pantries often

furnish subsistence not only to rats that inhabit the dwelling, but to

many that come from outside. Food supplies may always be kept

from rats and mice if placed in inexpensive rat-proof containers

covered with wire netting. Sometimes all that is needed to prevent

[Pg 10]

serious waste is the application of concrete to holes in the basement

wall or the slight repair of a defective part of the building.

Produce in transit.—Much loss of fruits, vegetables, and other produce

occurs in transit by rail and on ships. Most of the damage is

done at wharves and in railway stations, but there is also considerable

in ships' holds, especially to perishable produce brought from warm

latitudes. Much of this may be prevented by the use of rat-proof

cages at the docks, by the careful fumigation of seagoing vessels at

the end of each voyage, and by the frequent fumigation of vessels in

coastwise trade; but still more by replacing old and decrepit wharves

and station platforms with modern ones built of concrete.

Where cargoes are being loaded or unloaded at wharves or depots,

food liable to attack by rats may be temporarily safeguarded by being

placed in rat-proof cages, or pounds, constructed of wire netting.

Wooden boxes containing reserve food held in depots for a considerable

time or intended for shipment by sea may be made rat-proof by

light coverings of metal along the angles. This plan has long been in

use to protect naval stores on ships and in warehouses. It is based

on the fact that rats do not gnaw the plane surfaces of hard materials,

but attack doors, furniture, and boxes at the angles only.

Packing houses.—Packing houses and abattoirs are often sources

from which rats secure subsistence, especially where meats are prepared

for market in old buildings. In old-style cooling rooms with

double walls of wood and sawdust insulation, always a source of

annoyance because of rat infestation, the utmost vigilance is required

to prevent serious loss of meat products. On the other hand, packing

houses with modern construction and sanitary devices have no trouble

from rats or mice.

Garbage and waste.—Since much of the food of rats consists of

garbage and other waste materials, it is not enough to bar the animals

from markets, granaries, warehouses, and private food stores. Garbage

and offal of all kinds must be so disposed of that rats can not

obtain them.

In cities and towns an efficient system of garbage collection and

disposal should be established by ordinances. Waste from markets,

hotels, cafés and households should be collected in covered metal

receptacles and frequently emptied. Garbage should never be

dumped in or near towns, but should be utilized or promptly destroyed

by fire.

Rats find abundant food in country slaughterhouses; reform in the

management of these is badly needed. Such places are centers of rat

propagation. It is a common practice to leave offal of slaughtered

animals to be eaten by rats and swine, and this is the chief means of

perpetuating trichinæ in pork. The law should require that offal be

promptly cremated or otherwise disposed of. Country

slaughter[Pg 11]houses

should be as cleanly and as constantly inspected as abattoirs.

Another important source of rat food is found in remnants of lunches left

by employees in factories, stores, and public buildings. This food, which

alone is sufficient to attract and sustain a small army of rats, is commonly left

in waste baskets or other open receptacles. Strictly enforced rules requiring

all remnants of food to be deposited in covered metal vessels would make trapping

far more effective.

Military training camps, unless subjected to rigid

discipline in the matter of disposal of garbage and waste, soon

become centers of rat infestation. Waste from camps, deposited in

covered metal cans and collected daily, should be removed far from

the camp itself and either burned or utilized in approved modern

ways.

DESTROYING RATS AND MICE.

The Biological Survey has made numerous laboratory and field

experiments with various agencies for destroying rats and mice.

The results form the chief basis for the following recommendations:

TRAPS.

Owing to their cunning, it is not always easy to clear rats from

premises by trapping; if food is abundant, it is impossible. A few

adults refuse to enter the most innocent-looking trap. And yet trapping,

if persistently followed, is one of the most effective ways of

destroying the animals.

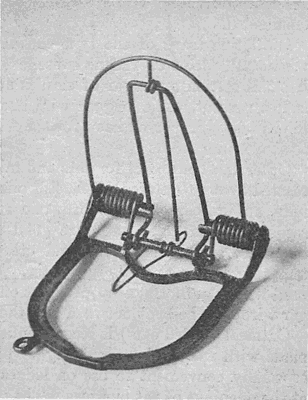

Fig. 5.—Guillotine

trap made entirely of metal.

Guillotine trap.—For general use the improved modern traps with a

wire fall released by a baited trigger and driven by a coiled spring

have marked advantages over the old forms, and many of them may

be used at the same time. These traps, sometimes called "guillotine"

traps, are of many designs, but the more simply constructed are preferable.

Probably those made entirely of metal are the best, as they

[Pg 12]

are more durable. Traps with tin or sheet-metal bases are not recommended.

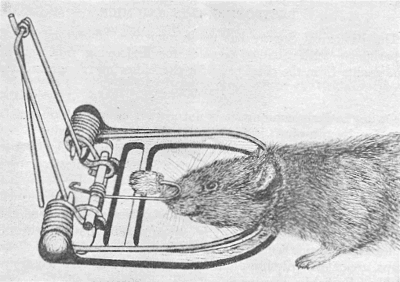

Guillotine traps of the type shown in figure 5 should be baited

with small pieces of Vienna sausage (Wienerwurst) or fried bacon.

A small section of an ear of corn is an excellent bait if other grain

is not present. The trigger wire should be bent inward to bring

the bait into proper position for the fall to strike the rat in the neck,

as shown in figure 6.

Other excellent baits for rats and mice are oatmeal, toasted cheese,

toasted bread (buttered), fish, fish offal, fresh liver, raw meat, pine

nuts, apples, carrots, and corn, and sunflower, squash, or pumpkin

seeds. Broken fresh eggs are good bait at all seasons, and ripe

tomatoes, green cucumbers, and other fresh vegetables are very

tempting to the animals in winter. When seed, grain, or meal is

used with a guillotine trap, it is put on the trigger plate, or the trigger

wire may be bent outward and the bait placed directly under it.

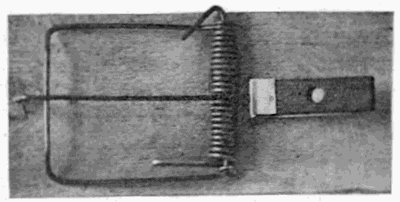

Oatmeal (rolled oats) is recommended as a bait for guillotine traps

made with wooden base and trigger plate (fig. 7). These traps are

especially convenient to use on ledges or other narrow rat runs or

at the openings of rat burrows. They are often used without bait.

Fig. 6.—Method

of baiting guillotine trap.

A common mistake in trapping for rats and mice is to use only

one or two traps when dozens are needed. For a large establishment

hundreds of traps may be used to advantage, and a dozen is none too

many for an ordinary barn or dwelling infested with rats. House

mice are less suspicious than rats and are much more easily trapped.

[Pg 13]

Small guillotine traps baited with oatmeal will soon rid

an ordinary dwelling of the smaller pests.

Fig. 7.—Guillotine

trap with wooden base and trigger plate.

Cage trap.—When rats are abundant, the large French

wire cage traps may be used to advantage. They should be made

of stiff wire, well reinforced. Many of those sold in stores are useless,

because a full-grown rat can bend the light wires apart and so escape.

Cage traps may be baited and left open for several nights until the

rats are accustomed to enter them to obtain food. They should then

be closed and freshly baited, when a larger catch may be expected,

especially of young rats (fig. 8). As many as 25, and even more,

partly grown rats have been taken at a time in one of these traps.

It is better to cover the trap than to leave it exposed. A short board

should be laid on the trap and an old cloth or bag or a bunch of hay

or straw thrown carelessly over the top. Often the trap may be

placed with the entrance opposite a rat hole and fitting it so closely

that rats can not pass through without entering the trap. If a single

rat is caught it may be left in the trap as a decoy to others.

Notwithstanding the fact that sometimes a large number of rats

may be taken at a time in cage traps, a few good guillotine traps

intelligently used will prove more effective in the long run.

Fig. 8.—Cage

trap with catch of rats.

Figure-4 trigger trap.—The old-fashioned box trap set with a figure-4

trigger is sometimes useful to secure a wise old rat that refuses

to be enticed into a modern trap. Better still is a simple

deadfall[Pg 14]—a

flat stone or a heavy plank—supported by a figure-4 trigger. An

old rat will go under such a contrivance to feed without fear.

Steel trap.—The ordinary steel trap (No. 0 or 1) may sometimes be

satisfactorily employed to capture a rat. The animal is usually

caught by the foot, and its squealing has a tendency to frighten other

rats. The trap may be set in a shallow pan or box and covered with

bran or oats, care being taken to have the space under the trigger pan free

of grain. This may be done by placing a very little cotton under the trigger

and setting as lightly as possible. In a narrow run or at the mouth of a burrow

a steel trap unbaited and covered with very light cloth or tissue paper is

often effective.

The best bait usually is food of a kind that the rats and mice do not

get in the vicinity. In a meat market, vegetables or grain should

be used; in a feed store, meat. As far as possible food other than

the bait should be inaccessible while trapping is in progress. The

bait should be kept fresh and attractive, and the kind changed when

necessary. Baits and traps should be handled as little as possible.

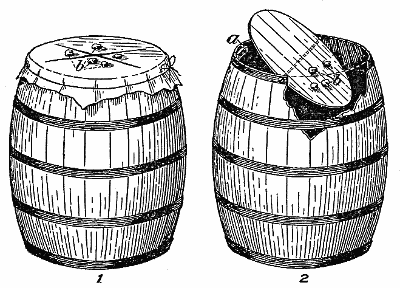

Fig. 9.—Barrel

trap: 1, With stiff paper cover; 2, with hinged barrel cover;

a, stop; b, baits.

Barrel trap.—About 60 years ago a writer in the Cornhill Magazine

gave details of a trap, by means of which it was claimed

that 3,000 rats were caught in a warehouse in a single night. The

plan involved tolling the rats to the place

and feeding them for several nights on the tops of barrels covered

with coarse brown paper. Afterwards a cross was cut in the paper,

so that the rats fell into the barrel (fig. 9 (1)). Many variations of

the plan, but few improvements upon it, have been suggested by agricultural

writers since that time. Reports are frequently made of large

catches of rats by means of a barrel fitted with a light cover of wood,

hinged on a rod so as to turn with the weight of a rat (fig. 9 (2)).

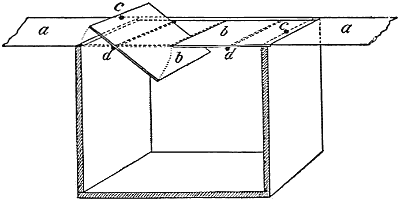

Fig. 10.—Pit trap.

aa, Rat run; bb, cover; cc, position of weights; dd, rods on which covers

turn.

[Pg 15]

Pit trap.—A modification of the barrel trap is the pit trap (fig. 10).

This consists of a stout narrow box sunk in the ground so that the

top is level with the rat run. It is fixed with a cover of light wood

or metal in two sections, the sections fitting nicely inside the box

and working independently. They turn on rods, to which they are

fastened. They are weighted near the ends of the box and so adjusted

that they swing easily. An animal stepping upon the cover

beyond the rods is precipitated into the box, while the cover immediately

swings back to its place. Besides rats, the trap is well

adapted to capture larger animals, as minks, raccoons, opossums, and

cats. It is especially useful to protect poultry yards, game preserves,

and the like. The trap should be placed along the fence outside the

yard, and behind a shelter of boards or brush that leans against the

fence.

Fence and battue.—In the rice fields of the Far East the natives

build numerous piles of brush and rice straw, and leave them for

several days until many rats have taken shelter in them. A portable

bamboo inclosure several feet in height is then set up around each

pile in succession and the straw and brush are thrown out over the

top, while dogs and men kill the trapped rodents. Large numbers

are destroyed in this way, and the plan with modifications may be

utilized in America with satisfactory results. A wire netting of fine

mesh may be used for the inclosure. The scheme is applicable at the

removal of grain, straw, or haystacks, as well as brush piles.

In a large barn near Washington, a few years ago, piles of unhusked

corn were left in the loft and were soon infested with rats.

A wooden pen was set down surrounding the piles in turn and the

corn thrown out until dogs were able to get at the rats. In this way

several men and dogs killed 500 rats in a single day.

POISONS.

While the use of poison is the best and quickest way to get rid of

rats and mice, the odor from the dead animals makes the method impracticable

in occupied houses. Poisons may be effectively used in

barns, stables, sheds, cribs, and other outbuildings.

Caution.—In the United States there are few laws which prohibit

the laying of poisons on lands owned or controlled by the poisoner.

Hence it is all the more necessary to exercise extreme caution to

prevent accidents. In several States notice of intention to lay poison

must be given to persons living in the neighborhood. Poison for

rats should never be placed in open or unsheltered places. This

applies particularly to strychnin or arsenic on meat. Packages containing

poisons should always bear a warning label and should not

be kept where children might reach them.

[Pg 16]

Among the principal poisons that have been recommended for

killing rats and mice are barium carbonate, strychnin, arsenic, phosphorus,

and squills.

Barium carbonate.—One of the cheapest and most effective poisons

for rats and mice is barium carbonate. This mineral has the advantage

of being without taste or smell. It has a corrosive action on the

mucous lining of the stomach and is dangerous to larger animals if

taken in sufficient quantity. In the small doses fed to rats and mice

it would be harmless to domestic animals. Its action upon rats is

slow, and if exit is possible the animals usually leave the premises in

search of water. For this reason the poison may frequently, though

not always, be used in houses without disagreeable consequences.

Barium carbonate may be fed in the form of dough composed of

four parts of meal or flour and one part of the mineral. A more

convenient bait is ordinary oatmeal with about one-eighth of its bulk

of the mineral, mixed with water into a stiff dough. A third plan is

to spread the barium carbonate upon fish, toasted bread (moistened),

or ordinary bread and butter. The prepared bait should be placed in

rat runs, about a teaspoonful at a place. If a single application of

the poison fails to kill or drive away all rats from the premises, it

should be repeated with a change of bait.

Strychnin.—Strychnin is too rapid in action to make its use for

rats desirable in houses, but elsewhere it may be employed effectively.

Strychnia sulphate is the best form to use. The dry crystals may be

inserted in small pieces of raw meat, Vienna sausage, or toasted

cheese, and these placed in rat runs or burrows; or oatmeal may be

moistened with a strychnin sirup and small quantities laid in the

same way.

Strychnin sirup is prepared as follows: Dissolve a half ounce of

strychnia sulphate in a pint of boiling water; add a pint of thick

sugar sirup and stir thoroughly. A smaller quantity may be prepared

with a proportional quantity of water and sirup. In preparing

the bait it is necessary to moisten all the oatmeal with the sirup.

Wheat and corn are excellent alternative baits. The grain should

be soaked overnight in the strychnin sirup.

Arsenic.—Arsenic is probably the most popular of the rat poisons,

owing to its cheapness, yet our experiments prove that, measured

by the results obtained, arsenic is dearer than strychnin. Besides,

arsenic is extremely variable in its effect upon rats, and if the animals

survive a first dose it is very difficult to induce them to take

another.

Powdered white arsenic (arsenious acid) may be fed to rats in

almost any of the baits mentioned under barium carbonate and

strychnin. It has been used successfully when rubbed into fresh

fish or spread on buttered toast. Another method is to mix twelve

[Pg 17]

parts by weight of corn meal and one part of arsenic with whites of

eggs into a stiff dough.

An old formula for poisoning rats and mice with arsenic is the

following, adapted from an English source:

Take a pound of oatmeal, a pound of coarse brown sugar, and a

spoonful of arsenic. Mix well together and put the composition into

an earthen jar. Put a tablespoonful at a place in runs frequented

by rats.

Phosphorus.—For poisoning rats and mice, phosphorus is used

almost as commonly as arsenic, and undoubtedly it is effective when

given in an attractive bait. The phosphorus paste of the drug

stores is usually dissolved yellow phosphorus, mixed with glucose or

other substances. The proportion of phosphorus varies from one-fourth

of 1 per cent to 4 per cent. The first amount is too small

to be always effective and the last is dangerously inflammable. When

homemade preparations of phosphorus are used there is much danger

of burning the person or of setting fire to crops or buildings.

In the Western States many fires have resulted from putting out

homemade phosphorus poisons for ground squirrels, and entire fields

of ripe grain have been destroyed in this way. Even with commercial

pastes the action of sun and rain changes the phosphorus

and leaches out the glucose until a highly inflammable residue is left.

It is often claimed that phosphorus eaten by rats or mice dries up

or mummifies the body so that no odor results. The statement has

no foundation in fact. No known poison will prevent decomposition

of the body of an animal that died from its effects. Equally misleading

is the statement that rats poisoned with phosphorus do not

die on the premises. Owing to its slower operation, no doubt a

larger portion escape into the open before dying than when strychnin

is used.

The Biological Survey does not recommend the use of phosphorus

as a poison for rodents.

Squills.—The squill, or sea leek,[6] is a favorite rat poison in many

parts of Europe and is well worthy of trial in America. It is rapid

and very deadly in its action, and rats seem to eat it readily. The

poison is used in several ways. Two ounces of dry squills, powdered,

may be thoroughly mixed with eight ounces of toasted cheese or of

butter and meal and put out in runs of rats or mice. Another formula

recommends two parts of squills to three parts of finely

chopped bacon, mixed with meal enough to make it cohere. This is

baked in small cakes.

Poison in poultry houses.—For poisoning rats in buildings and yards

occupied by poultry the following method is recommended: Two

[Pg 18]

wooden boxes should be used, one considerably larger than the other

and each having one or more holes in the sides large enough to

admit rats. The poisoned bait should be placed on the bottom and

near the middle of the smaller box, and the larger box should then

be inverted over it. Rats thus have free access to the bait, but fowls

are excluded.

DOMESTIC ANIMALS.

Among domestic animals employed to kill rats are the dog, the

cat, and the ferret.

Dogs.—The value of dogs as ratters can not be appreciated by persons

who have had no experience with a trained animal. The ordinary

cur and the larger breeds of dogs seldom develop the necessary

qualities for ratters. Small Irish, Scotch, and fox terriers, when

properly trained, are superior to other breeds and under favorable

circumstances may be relied upon to keep the farm premises reasonably

free from rats.

Cats.—However valuable cats may be as mousers, few learn to catch

rats. The ordinary house cat is too well fed and consequently too

lazy to undertake the capture of an animal as formidable as the

brown rat. Birds and mice are much more to its liking. Cats that

are fearless of rats, however, and have learned to hunt and destroy

them are often very useful about stables and warehouses. They

should be lightly fed, chiefly on milk. A little sulphur in the milk at

intervals is a corrective against the bad effects of a constant rat or

mouse diet. Cats often die from eating these rodents.

Ferrets.—Tame ferrets, like weasels, are inveterate foes of rats, and

can follow the rodents into their retreats. Under favorable circumstances

they are useful aids to the rat catcher, but their value is

greatly overestimated. For effective work they require experienced

handling and the additional services of a dog or two. Dogs and

ferrets must be thoroughly accustomed to each other, and the former

must be quiet and steady instead of noisy and excitable. The ferret

is used only to bolt the rats, which are killed by the dogs. If unmuzzled

ferrets are sent into rat retreats, they are apt to make a kill

and then lie up after sucking the blood of their victim. Sometimes

they remain for hours in the burrows or escape by other exits and

are lost. There is danger that these lost ferrets may adapt themselves

to wild conditions and become a pest by preying upon poultry

and birds.

FUMIGATION.

Rats may be destroyed in their burrows in the fields and along

river banks, levees, and dikes by carbon bisulphid.[7] A wad of

cot[Pg 19]ton

or other absorbent material is saturated with the liquid and

then pushed into the burrow, the opening being packed with earth to

prevent the escape of the gas. All animals in the burrow are asphyxiated.

Fumigation in buildings is not so satisfactory, because it is

difficult to confine the gases. Moreover, when effective, the odor

from the dead rats is highly objectionable in occupied buildings.

Chlorin, carbon monoxid, sulphur dioxid, and hydrocyanic acid

are the gases most used for destroying rats and mice in sheds, warehouses,

and stores. Each is effective if the gas can be confined and

made to reach the retreats of the animals. Owing to the great danger

from fire incident to burning charcoal or sulphur in open pans, a

special furnace provided with means for forcing the gas into the compartments

of vessels or buildings is generally employed.

Hydrocyanic-acid gas is effective in destroying all animal life in

buildings. It has been successfully used to free elevators and warehouses

of rats, mice, and insects. However, it is so dangerous to

human life that the novice should not attempt fumigation with it,

except under careful instructions. Directions for preparing and

using the gas may be found in a publication entitled Hydrocyanic-acid

Gas against Household Insects, by Dr. L. O. Howard and

Charles H. Popenoe.[8]

Carbon monoxid is rather dangerous, as its presence in the hold of

a vessel or other compartment is not manifest to the senses, and fatal

accidents have occurred during its employment to fumigate vessels.

Chlorin gas has a strong bleaching action upon textile fabrics, and

for this reason can not be used in many situations.

Sulphur dioxid also has a bleaching effect upon textiles, but less

marked than that of chlorin, and ordinarily it is not noticeable with

the small percentage of the gas it is necessary to use. On the whole,

this gas has many advantages as a fumigator and disinfectant. It is

used also as a fire extinguisher on board vessels. Special furnaces for

generating the gas and forcing it into the compartments of ships and

buildings are on the market, and many steamships and docks are

now fitted with the necessary apparatus.

RAT VIRUSES.

Several microorganisms, or bacteria, found originally in diseased

rats or mice, have been exploited for destroying rats. A number of

these so-called rat viruses are on the American market. The Biological

Survey, the Bureau of Animal Industry, and the United States

Public Health Service have made careful investigations and practical

tests of these viruses, mostly with negative results. The cultures

tested by the Biological Survey have not proved satisfactory.

The chief defects to be overcome before the cultures can be recommended

for general use are:

[Pg 20]

1. The virulence is not great enough to kill a sufficiently high percentage

of rats that eat food containing the microorganisms.

2. The virulence decreases with the age of the cultures. They deteriorate

in warm weather and in bright sunlight.

3. The diseases resulting from the microorganisms are not contagious

and do not spread by contact of diseased with healthy

animals.

4. The comparative cost of the cultures is too great for general use.

Since they have no advantages over the common poisons, except that

they are usually harmless to man and other animals, they should be

equally cheap; but their actual cost is much greater. Moreover, considering

the skill and care necessary in their preparation, it is doubtful

if the cost can be greatly reduced.

The Department of Agriculture, therefore, does not prepare, use,

or recommend the use of rat viruses.

NATURAL ENEMIES OF RATS AND MICE.

Among the natural enemies of rats and mice are the larger hawks

and owls, skunks, foxes, coyotes, weasels, minks, dogs, cats, and

ferrets.

Probably the greatest factor in the increase of rats, mice, and other

destructive rodents in the United States has been the persistent killing

off of the birds and mammals that prey upon them. Animals that

on the whole are decidedly beneficial, since they subsist upon harmful

insects and rodents, are habitually destroyed by some farmers and

sportsmen because they occasionally kill a chicken or a game bird.

The value of carnivorous mammals and the larger birds of prey in

destroying rats and mice should be more fully recognized, especially

by the farmer and the game preserver. Rats actually destroy more

poultry and game, both eggs and young chicks, than all the birds and

wild mammals combined; yet some of their enemies among our most

useful birds of prey and carnivorous mammals are persecuted almost

to the point of extinction. An enlightened public sentiment should

cause the repeal of all bounties on these animals and afford protection

to the majority of them.

ORGANIZED EFFORTS TO DESTROY RATS.

The necessity of cooperation and organization in the work of rat

destruction is of the utmost importance. To destroy all the animals

on the premises of a single farmer in a community has little permanent

value, since they are soon replaced from near-by farms. If,

however, the farmers of an entire township or county unite in efforts

to get rid of rats, much more lasting results may be attained. If continued

from year to year, such organized efforts are very effective.

COMMUNITY EFFORTS.

Cooperative efforts to destroy rats have taken various forms in

different localities. In cities, municipal employees have occasionally

been set at work hunting rats from their retreats, with at least temporary

benefit to the community. Thus, in 1904, at Folkestone, England,

a town of about 25,000 inhabitants, the corporation employees,

helped by dogs, in three days killed 1,645 rats.

Side hunts in which rats are the only animals that count in the

contest have sometimes been organized and successfully carried out.

At New Burlington, Ohio, a rat hunt took place some years ago in

which each of the two sides killed over 8,000 rats, the beaten party

serving a banquet to the winners.

There is danger that organized rat hunts will be followed by long

intervals of indifference and inaction. This may be prevented by

offering prizes covering a definite period of effort. Such prizes

accomplish more than municipal bounties, because they secure a

friendly rivalry which stimulates the contestants to do their utmost

to win.

In England and some of its colonies contests for prizes have been

organized to promote the destruction of the English, or house, sparrow,

but many of the so-called sparrow clubs are really sparrow and

rat clubs, for the destruction of both pests is the avowed object of

the organizations. A sparrow club in Kent, England, accomplished

the destruction of 28,000 sparrows and 16,000 rats in three seasons

by the annual expenditure of but £6 ($29.20) in prize money. Had

ordinary bounties been paid for this destruction, the tax on the community

would have been about £250 (over $1,200).

Many organizations already formed should be interested in destroying

rats. Boards of trade, civic societies, and citizens' associations

in towns and farmers' and women's clubs in rural communities

will find the subject of great importance. Women's municipal

leagues in several large cities already have taken up the matter.

The league in Baltimore recently secured appropriations of funds

for expenditure in fighting mosquitoes, flies, and rats. The league

in Boston during the past year, supported by voluntary contributions

for the purpose, made a highly creditable educational campaign

against rats. Boys' corn clubs, the troops of Boy Scouts, and

similar organizations could do excellent work in rat campaigns.

STATE AND NATIONAL AID.

To secure permanent results any general campaign for the elimination

of rats must aim at building the animals out of shelter and food.

Building reforms depend on municipal ordinances and legislative

[Pg 22]

enactments. The recent plague eradication work of the United

States Public Health Service in San Francisco, Seattle, New Orleans,

and at various places in Hawaii and Porto Rico required such ordinances

and laws as well as financial aid in prosecuting the work.

The campaign of Danish and Swedish organizations for the destruction

of rats had the help of governmental appropriations. The legislatures

of California, Texas, Indiana, and Hawaii have in recent

years passed laws or made appropriations to aid in rat riddance. It is

probable that well-organized efforts of communities would soon win

legislative support everywhere. Communities should not postpone

efforts, however, while waiting for legislative cooperation, but should

at once organize and begin repressive operations. Wherever health

is threatened the Public Health Service of the United States can cooperate,

and where crops and other products are endangered the

Bureau of Biological Survey of the Department of Agriculture is

ready to assist by advice and in demonstration of methods.

IMPORTANT REPRESSIVE MEASURES.

The measures needed for repressing and eliminating rats and mice

include the following:

1. The requirement that all new buildings erected shall be made

rat-proof under competent inspection.

2. That all existing rat-proof buildings shall be closed against rats

and mice by having all openings accessible to the animals, from

foundation to roof, closed or screened by door, window, grating, or

meshed wire netting.

3. That all buildings not of rat-proof construction shall be made so

by remodeling, by the use of materials that may not be pierced by

rats, or by elevation.

4. The protection of our native hawks, owls, and smaller predatory

mammals—the natural enemies of rats.

5. Greater cleanliness about markets, grocery stores, warehouses,

courts, alleys, stables, and vacant lots in cities and villages, and like

care on farms and suburban premises. This includes the storage of

waste and garbage in tightly covered vessels and the prompt disposal

of it each day.

6. Care in the construction of drains and sewers, so as not to provide

entrance and retreat for rats. Old brick sewers in cities should

be replaced by concrete or tile.

7. The early threshing and marketing of grains on farms, so that

stacks and mows shall not furnish harborage and food for rats.

8. Removal of outlying straw stacks and piles of trash or lumber

that harbor rats in fields and vacant lots.

[Pg 23]

9. The keeping of provisions, seed grain, and foodstuffs in rat-proof containers.

10. Keeping effective rat dogs, especially on farms and in city warehouses.

11. The systematic destruction of rats, whenever and wherever

possible, by (a) trapping, (b) poisoning, and (c) organized hunts.

12. The organization of clubs and other societies for systematic

warfare against rats.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Mus musculus.

[2] Rattus norvegicus.

[3] Rattus rattus rattus.

[4] Rattus rattus alexandrinus.

[5] Farmers' Bulletin 461, Use of Concrete on the Farm, will prove useful to city and

village dwellers as well as to the farmer.

[6] Scilla maritima.

[7] Caution.—Carbon disulphid is very inflammable and can be ignited by a match, lantern,

cigar, or pipe.

[8] Farmers' Bulletin 699.

PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

RELATING TO NOXIOUS MAMMALS.

AVAILABLE FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION.

How to Destroy Rats. (Farmers' Bulletin 369.)

The Common Mole of Eastern United States. (Farmers' Bulletin 583.)

Field Mice as Farm and Orchard Pests. (Farmers' Bulletin 670.)

Cottontail Rabbits in Relation to Trees and Farm Crops. (Farmers' Bulletin

702.)

Trapping Moles and Utilizing Their Skins. (Farmers' Bulletin 832.)

Destroying Rodent Pests on the Farm. (Separate 708, Yearbook for 1916.)

FOR SALE BY THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS, GOVERNMENT PRINTING

OFFICE, WASHINGTON, D. C.

Harmful and Beneficial Mammals of the Arid Interior, with Special Reference

to the Carson and Humboldt Valleys, Nevada. (Farmers' Bulletin 335.)

Price 5 cents.

The Nevada Mouse Plague of 1907-8. (Farmers' Bulletin 352.) Price 5 cents.

Some Common Mammals of Western Montana in Relation to Agriculture and

Spotted Fever. (Farmers' Bulletin 484.) Price 5 cents.

Danger of Introducing Noxious Animals and Birds. (Separate 132, Yearbook

1898.) Price 5 cents.

Meadow Mice in Relation to Agriculture and Horticulture. (Separate 388, Yearbook

1905.) Price 5 cents.

Mouse Plagues, Their Control and Prevention. (Separate 482, Yearbook 1908.)

Price—cents.

Use of Poisons for Destroying Noxious Mammals. (Separate 491, Yearbook

1908.) Price 5 cents.

Pocket Gophers as Enemies of Trees. (Separate 506, Yearbook 1909.) Price

5 cents.

The Jack Rabbits of the United States. (Biological Survey Bulletin 8.) Price

10 cents.

Economic Study of Field Mice, genus Microtus. (Biological Survey Bulletin 31.)

Price 15 cents.

The Brown Rat in the United States. (Biological Survey Bulletin 33.) Price

15 cents.

Directions for the Destruction of Wolves and Coyotes. (Biological Survey Circular

55.) Price 5 cents.

The California Ground Squirrel. (Biological Survey Circular 76.) Price 5

cents.

Seed-eating Mammals in Relation to Reforestation. (Biological Survey Circular

78.) Price 5 cents.

Mammals of Bitterroot Valley, Montana, in Their Relation to Spotted Fever.

(Biological Survey Circular 82.) Price 5 cents.

Transcriber's Note

The following suspected errors have been changed in this text:

Page 11: "abbatoirs" changed to "abattoirs"

Page 11: Added missing "." to "Fig. 5."

Page 14: Added missing "." to "Fig. 10."

Featured Books

Tik-Tok of Oz

L. Frank Baum

with Ojo the Lucky. As you know,I am obliged to talk these matters over with Dorothy by means of th...

The Postnatal Development of Two Broods of Great Horned Owls (Bubo virginianus)

Donald Frederick Hoffmeister and Henry W. Setzer

story at the University of Kansas. Theobservations here reported are based primarily on the three yo...

Description of a New Softshell Turtle from the Southeastern United States

Robert G. Webb

klin Sogandares-Bernal, Ernest A. Liner,Donald W. Tinkle, Paul K. Anderson, and John K. Greer. Theph...

The Adductor Muscles of the Jaw In Some Primitive Reptiles

Richard C. Fox

muscles on the skeletons of the fossils andby studying the anatomy of Recent genera. A reconstructio...

Gascoyne, The Sandal-Wood Trader: A Tale of the Pacific

R. M. Ballantyne

R XIV.Greater Mysteries than Ever—A Bold Move and Clever EscapeCHAPTER XV.Remarkable Doings of Poo...

Samantha among the Brethren — Volume 3

Marietta Holley

stands to reason it is. And I'd like to knowwhat you have got to say about him any way?"Sez I, "That...

The Devil's Dictionary

Ambrose Bierce

ime, too, some of the enterprising humorists of the country had helped themselves to such parts...

Mizora: A Prophecy

Mary E. Bradley Lane

messages about it, and letters of inquiry, and someladies and gentlemen desired to know the particu...

Browse by Category

Join Our Literary Community

Subscribe to our newsletter for exclusive book recommendations, author interviews, and upcoming releases.

Comments on "House Rats and Mice" :